Red Deer Industrial Institute

Dates of Operation

1893–1919

Operated by the Missionary Society of the Methodist Church (Canada), although in the school’s first year, the Department of Indian Affairs was responsible for staff appointments and salaries

Location

Three miles west of Red Deer, Alberta, on the opposite bank of the Red Deer River.

A few weeks ago, our Indian pupils, by unanimous vote, requested Mr. Barner, the Principal, to take the money that would be expended upon them for presents and give it to the missionaries upon the different reserves from whence our boys and girls have come, to be used in making the children there a little happier, and give them an “extra treat.” This was gladly done by Mr. Barner, and letters of thanks were read at the entertainment from the different missionaries on these reserves, thus making our evening together not only very enjoyable, but a time of inspiration to do greater things to make others happy, that are not so favoured as we.

—The Christian Guardian, 1910, describing for a Methodist readership Christmas at Red Deer Residential School [1]

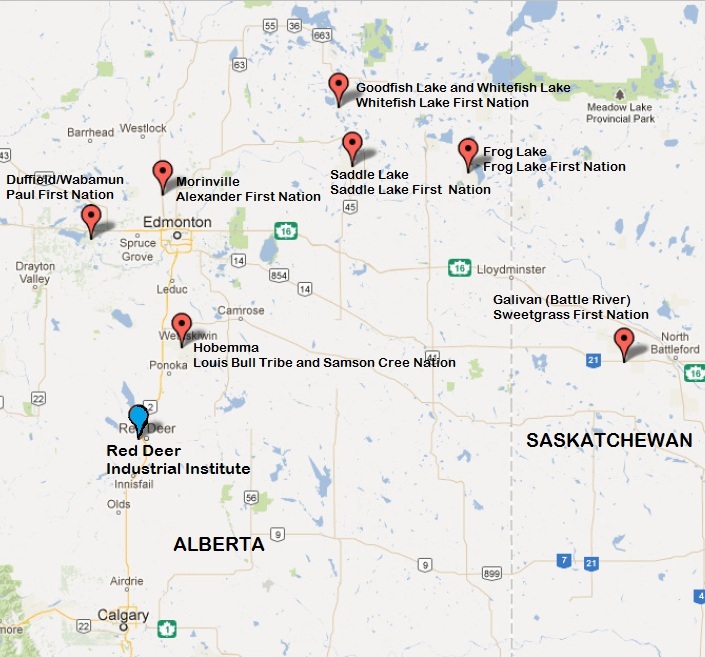

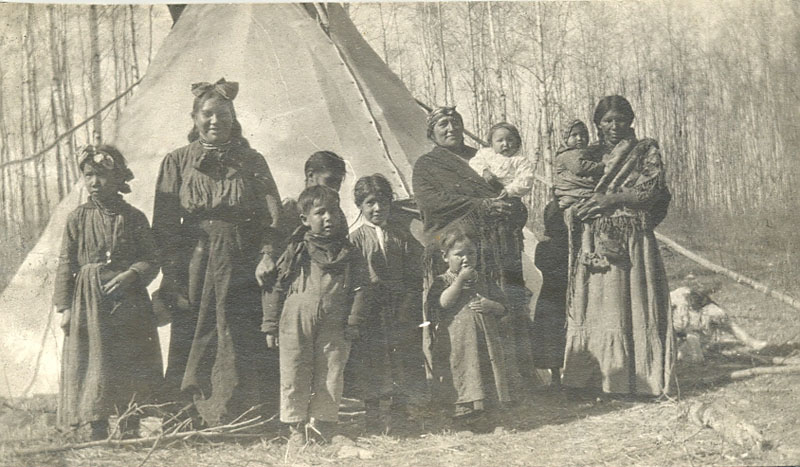

Red Deer was the first Methodist industrial institute in what would become the province of Alberta. When it opened in 1893, the school was not much larger than the mission boarding schools already in place on reserves in the region, but unlike those schools, it was built at a great distance from the communities it was meant to serve—the signing Cree and Saulteaux nations of Treaty 6, who lived around and north of Edmonton. Located five kilometres west of Red Deer, the nearest reserve was 65 kilometres away. This distance contributed to the school’s eventual demise, since the Edmonton, Hobbema, and Saddle Lake First Nations preferred to keep their children closer to home. In 1919, Red Deer Industrial Institute was closed, to be replaced by Edmonton Residential School.

Establishment

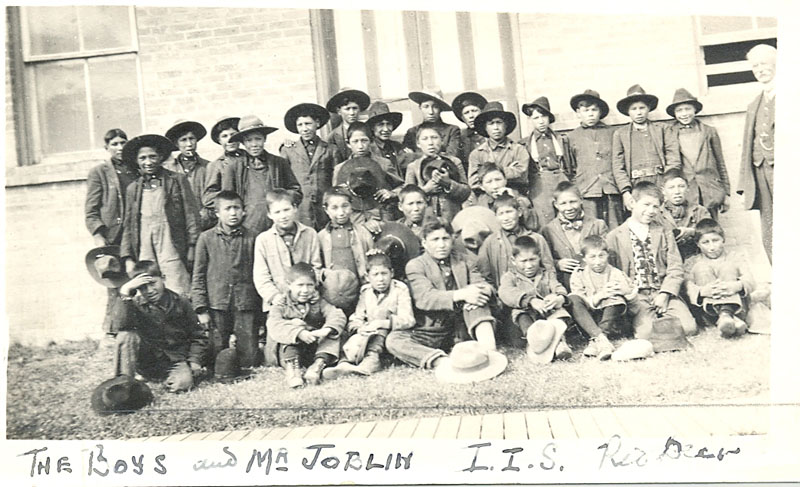

Built by the Department of Indian Affairs on 480 acres on the banks of the Red Deer River, the main building was a two-storey stone structure with accommodation for 50 students. Outbuildings included a staff cottage, carpenter and shoemaker shop, blacksmith shop, piggery (but no pigs), stable with lean-to, hen-house, and bakery-laundry. The plan was to clear the land, “a veritable forest,” according to John Nelson, the school’s first principal, to serve as a commercial farm.[2] Another 640 acres was reserved for the school’s use as hay lands. Nineteen students registered by July 14, 1893, but by the time of the school’s official opening in September, that number had grown to 52[3] Boys outnumbered girls almost two to one, a ratio that would not change significantly during the school’s existence. The school depended on the children’s labour; they worked before and after their classes, preparing the grounds, clearing brush, and digging stumps. The boys broke 26 acres in the first year and cut 8,000 rails—200 hundred each and every day. [4] The crop the first year consisted of 14.5 acres of oats, 2 of potatoes, 2.5 of turnips, and a quarter acre of carrots and a garden. The stable housed a herd of 4 oxen, 20 cows, and 10 calves.[5]

Principal Nelson had a difficult time administering the school: the building was already overcrowded, but 50 students were not enough to run it on the per capita grant of $130 the DIA began to provide at the end of the 1894/95 school year. In addition, there was “want of harmony between the Principal and some of the employees,” who had been appointed by the DIA and were, in the Missionary Society’s view, overpaid and, in some cases, unqualified. The society demanded another building so as to increase enrolment, as well as a schoolhouse and a playroom for the boys. “With the limited accommodation it is next to impossible to secure that separation of the sexes which is so important for the character and efficiency of such an institution,” wrote General Secretary A. Sutherland. Sutherland pointed out that the government had agreed to cover the costs of building and maintaining the school until enough students were secured to run it on a per capita basis. He threatened to withdraw the society from their agreement to manage the institute if the DIA did not make the required changes.[6]

Changes were made. In 1897, a second three-storey building was built with a playroom for the boys on the ground floor, dormitories for the older boys on the second, and schoolrooms and a chapel above that. A house for Principal C.E. Somerset, who had replaced Nelson the year before, was also built. Boys under the age of ten remained with the girls in the first building. Accommodation now existed for 90 students, 10 staff, and the principal, but filling the school turned out to be a challenge neither the Missionary Society nor the DIA was able to overcome.

Curriculum

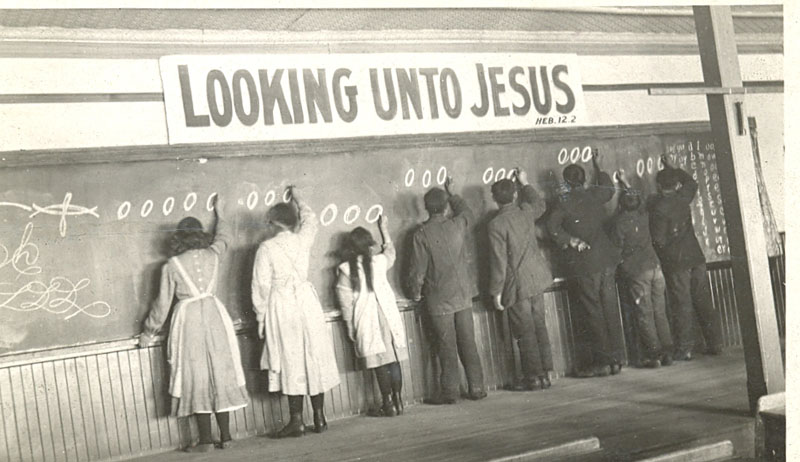

As an industrial institute, Red Deer’s mandate was, in addition to providing academic and religious instruction, to train its students in certain trades—carpentry, shoemaking and blacksmithing—as well as farming. The school was outfitted with a blacksmith shop from the outset, but it appears that instructors for this trade were never hired. Instead, in the school’s early years, interested students learned it “in the village.”[7] Shoemaking saw a similar fate: the shoemaking shop opened in the fall of 1895 but appears to have closed again by the following year.

In the case of carpentry, a number of boys were initially kept busy with construction projects at the school. Between 1895 and 1899, they built a dairy, remodelled the laundry to serve as a dwelling, erected a cattle stable, added a kitchen to one of the cottages, made storm and mosquito sashes for the principal’s house and the new boy’s dormitory building, put down sidewalks and made gates, as well as fashioning ladders and benches for the school’s use. In short, they did “all the building, painting and repairing” the school required.[8] However, by 1908, carpentry instruction had been abandoned because of low attendance and because students were no longer allowed to work away from the institution.”[9]

As well as farming and carpentry, boys were expected to sew on their own buttons, do some mending, and help in the laundry. They also did the milking.

In the opinion of one DIA inspector, nothing was lost by not teaching trades at the school. In speaking of industrial institutes generally, he wrote in 1902, “I have tried to discourage the introduction or even continuance of so many shops which are not likely to turn out any but a small number of good mechanics. It is a waste of funds to employ an expert craftsman to train a mere handful of pupils who in the end may be unable to turn their knowledge to advantage.”[10] However, not everyone involved in “Indian work” in Alberta took this view. The farmer-in-charge on the Stoney Reserve in 1900 criticized what he considered an undue focus on farming at Red Deer Residential School: “It is curious to note that the only three pupils attending this school lately have been taught the trade of farmer, instead of being taught a trade which would be useful to them.”[11]

Girls at Red Deer Residential School were taught “white women’s housekeeping,” which included cooking and baking, laundry, butter making, and sewing as well as health rules and sanitation. Their domestic labour contributed to the running of the school: “All their clothes are made by themselves, also the house linen, boys’ shirts and night-shirts; they knit all the socks and mitts, do all the darning and mending.”[12] In 1901, “after great difficulty and many objections on the part of parents,” the school arranged to discharge some girl students to domestic service, a practice that continued for many years.[13]

School authorities also hoped that the girls would be married upon graduation. In fact, they often took an active role in brokering marital unions, both recommending and vetoing potential partners. The moral education of girls, in particular, was an ongoing concern in the Methodist schools, and sometimes “misbehaving” girls were sent there to reform. One such case at Red Deer Residential School saw a 15-year-old girl “tried” and ordered by the Indian Agent to attend the school because she was considered “detrimental to the moral life of [her] reserve.”[14] The girl died two years later in Brandon, Manitoba.[15]

On the academic front, the children progressed well in arithmetic, but lagged, in the view of several officials, in learning English. One reason, given by Principal Nelson, was that a number of the staff spoke Cree. To improve the students’ English skills, he required that every evening each pupil “speak at least one English sentence of their own composition.”[16] He also held weekly evenings of recitations, singing and addresses by the pupils in English. Despite these efforts, in 1903, a school inspector still remarked, “A serious drawback to school work, as well as an evidence of bad discipline, was the use of the Cree language, which was quite prevalent.”[17] In 1907, another remarked, “Very little improvement was noticed with regard to the pupils either reading or speaking in a sufficiently audible tone to be heard.”[18] The ability to speak English was one of the skills that administrators highlighted in their drives to recruit students. On a visit to Saddle Lake, for example, Nelson brought two students with him and had them address the community in English and Cree.[19]

Farm

A great deal of the children’s time at Red Deer Residential School was spent working on the farm. Although the land was excellent for agriculture, it was often affected by frosts and flooding and occasionally by droughts. Early on the school gave up on the hay lands reserved for their use because they were always under water. Students worked hard to increase the acreage under cultivation, from 26 acres in the school’s first year of operations to 105 in 1900 (63 acres of oats, ten of barley, ten of green feed, ten of hay, two of spelt, and ten of garden).[20] That year the school leased another 640 acres for grazing its animals.

Principal J.P. Rice, appointed in 1903, intensified farming even further, with the boys breaking new ground at a rate of 75 acres a year. By 1905, he had more than 300 acres under cultivation. At that point, in addition to planting, tending, and harvesting the crop, students cared for 10 horses, 80 head of cattle, 50 hogs, 12 sheep and 150 poultry.[21] One inspector, who saw little improvement in the children’s academic studies, wrote, “The farming operations are now so extensive that a number of the pupils have spent more than half their time at industrial work.”[22]

Arthur Barner, who became principal in 1907, reduced the area of land under cultivation to about 200 acres and invested in steers to be primed for the market. His farm instructor also “encouraged” the boys to keep small individual gardens on their own time.[23]

Despite these initiatives, the farm did not produce well enough to keep the school out of debt. The Board of Missions noted on Barner’s resignation in 1913 that during the previous six years the church had spent $16,000 in order to keep the place running. This was due in part to poor results on the farm: “The crop was hailed out in two of the six years and in two other years the rain was so continuous that they were unable to harvest the crop, it being impossible to cut it because of the mud before it got frozen.”[24] Barner’s successor, J.F. Woodsworth, nonetheless continued to work the farm until Red Deer Residential School closed in 1919.

Recruiting

Cree families resisted sending their children to the unpopular Red Deer Residential School.[25] In 1897, the year after Red Deer Residential School was enlarged to accommodate 90 students, enrolment was 71. From there it declined steadily, and by 1902 only 57 students were registered. Attendance picked up briefly under Principal Rice, but soon began to fall again. By 1908, a mere 43 students were enrolled. The situation led one DIA inspector to recommend cutting off further funding to the school: “Unless there is a marked change in the attitude of the Indians towards this school in the near future, I do not see many reasons for keeping it in operation.”[26]

From the school’s first years, administrators remarked on the difficulty of attracting students. Principal Somerset noted parents’ “indifference” to the school and recommended resorting to compulsion to secure attendance.[27] Under his successor, recruitment for the school remained “a serious problem.”[28] Principal Arthur Barner concluded that “nothing less than a house-to-house visitation for the purpose of an educational campaign among the adult Indians would ever bring the tide towards this institute.”[29]

Parents were reluctant to send their children to the school because of its great distance from their homes, its run-down state, and its poor reputation. For some administrators, the problems at Red Deer were symptomatic of Residential schools in general. Residential schools, they argued, were unsuccessful at assimilating Indigenous children to Christian, “civilized” living but left graduates “in between” two cultures. One wrote after his inspection of Red Deer in 1903, “The attempt to civilize our Indians by breaking up the ties of home and alienating them from their natural associations has proved a general failure, and accounts for the fact that in many instances ex-pupils of the school on returning to the reserves are found by the agents to be intractable and unsettled, scorning in a measure their Indian connections, yet quite unable to think or live like white men.”[30] Instead of seeing the community’s indifference as a form of resistance to imposed schooling, the Indian Agent of the Blackfoot reserve concluded that industrial schools fostered dependency: “They become mere machines, and, like a clock that is run down, they simply lie around and wait until some one comes along and winds them up again.” He also argued that boarding schools on the reserves were more practical and less expensive.[31]

The fact that Red Deer Residential School did not allow its students any holiday time contributed to its unpopularity, as did the intensive farm work required of the children. Principal Barner introduced a one-month vacation period in the hopes of improving relations with the childrens’ home communities. “The boys were worked so hard on the farm by the late principal [Rice], that there may be a gain in the popularity of the school by such a month’s vacation,” the Indian Commissioner observed when recommending the change.[32] Barner canvassed the Indigenous communities, seeking to convince them that the sacrifice of sending their children away to school was worthwhile. He also sought to improve living conditions and the general health of his students. In response, attendance rose, truancy fell, and by the end of his term the school was nearly full. He reported in 1912, “Even Hobbema, which reserve has held out stubbornly against sending any pupils ever since I came here five years ago has, during the past year, sent six pupils.”[33]

Conditions and Student Health

When medical officer Peter Bryce penned his 1907 report on the poor health and high death rates of children who attended residential schools, Red Deer Residential School had the dubious distinction of reporting the most deaths during the year of his investigation. According to Bryce, six children had died during the 1906/07 school year.[34] Sickness and death was not new to Red Deer. Principals regularly reported at least one or two deaths a year, and in 1889 four children died from pneumonia following a measles epidemic.[35] These numbers, however, do not refect the full extent of fatalities among residential school students because children were routinely discharged from school when they showed signs of tuberculosis or other serious illnesses. Bryce estimated that the death rate at the schools was about 25 percent but rose to 40 percent when the children who were sent home were taken into account. At Red Deer, in 1902, six children—three of them newcomers from the Hudson Bay area—died from tuberculosis. Principal Somerset, clearly distressed, wrote in his 1903 annual report, “It is a question if the change of life has not been greater than the children could stand—from the wild, free life, living largely upon fish, to the confined life here.”[36] Somerset left the school the same year.

Principal Rice, who replaced him, was stunned by the state of the school and its children: “A glance at the buildings and the sight of the ragged, unkempt and sickly looking children was sufficient to make me sick at heart.”[37] A DIA official laid some of the blame for this state of affairs on Somerset, whose reports, he concluded, must have been misleading, but he also recognized that both the DIA and the Methodist Church had been “lax” in monitoring the school, since “years were allowed to pass without any inspection being made.”[38]

Poor ventilation and heating along with crowded dormitories allowed tuberculosis to thrive. Rice made some improvements to the school, the two most important being new sewers and a new water system providing “good spring water” instead of the “impure” water the school had used since it opened.[39] Rice also sought to keep the children in the open air as much as possible and to isolate the sick from the rest of the student population. He set up a hospital tent, with a stove to heat it, where sick children could be tended in the fresh air, and he proposed conducting at least some classes out of doors.[40]

Still, with low student enrolment and the school dependent on per capita grants, conditions once again deteriorated. With the onset of World War I, the government diverted both its attention and most of its funds to the war effort. From 1904 to the armistice, no money was spent on improvements at Red Deer Residential School at all.

A number of the children who died at the school were buried in a small cemetery there. In 2008, an archaeological survey, prompted in part by plans to develop a subdivision, located the remains of 18 individuals and a number of wooden headstones.>[41] Then, in 2005, members of Sunnybrook United Church, in an effort to build better relations with Indigenous peoples in the region, began to research the cemetery and the school, successfully identifying 12 of the people buried there. These included 13-year-old David Laroque, who died of tuberculosis, and 14-year-old Irene Stoney, of the Enoch Band, who died of tuberculosis after contracting the flu and spent her final days in a tent on the school grounds.[42]

Staff

Qualified staff for Red Deer Residential School was hard to come by and harder to keep. Wages were low, the school was isolated, and the work was trying. In 1903, Principal Somerset wrote, “This institute has suffered in the past very greatly because trained assistants were not to be obtained.”[43] An inspector’s report for the same period stated that there had been seven different changes in teachers in the previous three and a half years.[44] In 1902, a teacher telegraphed the minister of the interior claiming that boys at the school were armed with knives and beyond the principal’s control, a report both the principal and the official who investigated stated was “completely false.”[45] With time, however, the teaching staff stabilized. W.B. Shaw, was at the school from 1908 to 1910, and F.J. Dodson, who succeeded him, was there until at least 1915.

Closing

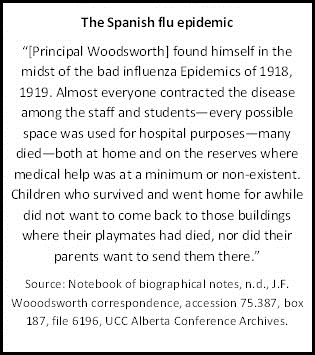

In June 1919, Principal Woodsworth recommended relocating the institute. Although attendance had improved under Principal Barner, Woodsworth attributed this change principally to a government promise that boarding schools would soon be established on the students’ home reserves. When the government abandoned its plan, Indigenous communities once again stopped sending their children. “Next year there will be only twelve girls old and young to do the work of the institution,” he wrote. [46] Woodsworth’s proposal also stemmed from his desire to protect the children from bad memories of the recent Spanish flu epidemic and a subsequent outbreak of smallpox.[47] Church and government officials agreed that relocation was necessary, and Red Deer Residential School was closed in July 1919. A site for a new school, closer to the Indigenous communities served by Red Deer Industrial Institute, was chosen just outside of Edmonton. In 1924, the new school would open as Edmonton Residential School.

Footnotes

- “Indian Industrial School at Red Deer,” The Christian Guardian, Jan. 19, 1910. ↩

- John Nelson, principal, to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), Aug. 27, 1894, Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual reports, 1895, pp. 91–92. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1894, pp. 117–120; Nelson to SGIA, Aug. 27, 1894. ↩

- Nelson to SGIA, Aug. 27, 1894. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1894, pp. 117–120. ↩

- A. Sutherland, General Secretary, Missionary Society, to SGIA, Jan. 3, [1896?], RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- C.E. Somerset, principal, to SGIA, July 21, 1897, DIA annual reports, 1897, pp. 269–271. ↩

- Somerset to SGIA, July 21, 1899, DIA annual reports, 1899, pp. 356–357. ↩

- Arthur Barner, principal, to Frank Pedley, Deputy SGIA, Apr. 7, 1909, DIA annual reports, 1909, pp. 382–385. ↩

- “Industrial Schools,” DIA annual reports, 1902, p. 191. ↩

- H.E. Sibbald, farmer-in-charge, to Sir, Nov. 13, 1900, extract of letter, RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” DIA annuals reports, 1899, pp. 383–385; J.F. Woodsworth, “Story of Indian Residential School,” n.d., accession 75.387, box 187, file 6198, UCC Alberta Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Somerset, to SIGA, July 31, 1901, DIA annual reports, 1901, pp. 370–371. ↩

- G.H. Race, Indian Agent, to Secretary, DIA, c. Jan 24, 1918, and Chief Paul Firebag et al, to Race, Oct. 1, 1917, both in RG10, vol. 10412, Shannon box 40, 1916–1919, LAC. ↩

- Race to F.J. Dodson, missionary teacher, June 24, 1920, RG10, vol. 10412, Shannon box 40, 1920–1932, LAC. ↩

- Nelson to SGIA, Aug. 27, 1894. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” DIA annual reports, 1903, pp. 456–457. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” DIA annual reports, 1907, pp. 383–384 ↩

- Nelson to Assistant Commissioner, June 6, 1895, RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- Somerset to SGIA, July 17, 1902, DIA annual reports, 1902, pp. 365–366. ↩

- J.P. Rice, principal, to Pedley, July 15, 1906, DIA annual reports, 1906, pp. 414-416. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” DIA annual reports, 1907. ↩

- Barner to Pedley, Apr. 30, 1908, DIA annual reports, pp. 387-390. ↩

- Thompson Ferrier, Superintendent of Missions, to Secretary, DIA, Apr. 21, [1913?], RG10, vol. 3921, file 116,818-1B, LAC. ↩

- Ferrier to C.E. Manning, General Secretary of Home Missions, July 1, 1925, accession 1986.158C, box 1, file 1, UCCA. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” 1909. ↩

- Somerset to SGIA, July 21, 1899. ↩

- Ferrier to Pedley, June 24, 1907, DIA annual reports, 1907, pp. 376–377.↩

- Barner to Pedley, Apr. 7, 1909. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” 1903. ↩

- G.H. Gooderham, Indian Agent, cited in DIA annual reports, 1909, pp. 321.↩

- D. Laird, Indian Commissioner, to Secretary, DIA, Apr. 19, 1908, RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- “The Report of Rev. Arthur Barner, Principal of the Red Deer Industrial Institute, Red Deer, Alta., for the Year Ended March 31, 1912,” DIA annual reports, 1912, pp. 545–547.↩

- Peter Henderson Bryce, Report on the Indian schools of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1907). ↩

- Register of Pupils, accession 79.268/162, item 162, O.S., UCC Alberta Regional Council Archives.↩

- Somerset, to SGIA, July 6, 1903, DIA annual reports, pp. 399–400.

- Rice to Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior, Aug. 3, 1903, RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- Martin Benson to Deputy SGIA, Aug. 12, 1903, RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- Rice to SGIA, Aug. 15, 1904, DIA annual reports, 1904, pp. 279–283. ↩

- Laird to Secretary, DIA, Aug. 24, 1904, RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- “Feast and Ceremony to Honour Native Children,” Mar. 4, 2010; “Residential School Graves to be Preserved,” July 2, 2010. ↩

- Register of Pupils, accession 79.268/162, item 162, O.S., UCC Alberta Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Somerset to SGIA, July 6, 1903. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” 1903. ↩

- Thomas Ross to Hon. Clifford Sifton, telegram, Apr. 21, [1902]; W.A. Collingham to James Smart, telegram, Apr. 22, [1902]; and Somerset to Smart, Apr. 23, [1902]—all in RG10, vol. 3920, file 116,818, LAC. ↩

- “Red Deer Industrial School,” 1903.↩

- Notebook of biographical notes, n.d., J.F. Woodworth correspondence, accession 75.387, box 187, file 6196, UCC Alberta Regional Council Archives. ↩