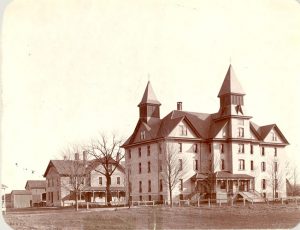

Mount Elgin Residential School

Mount Elgin Residential School Timeline

Dates of Operation

1851–1862, 1867–1946

Operated by the Missionary Society of the Wesleyan Methodist church in Canada, and after 1925, by the Board of Home Missions of The United Church of Canada.

Location

On what is now the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation No. 42, in Muncey, 20 miles southwest of London, Ontario. The land occupied by the school also bordered on the reserve of the Oneida Nation of the Thames, from which it leased several hundred acres of pasture land. Mount Elgin was also known as the Muncey Institute.

You had five minutes to get up when the first bell would ring, five minutes to get up and put your clothes on, five minutes to run two flights of stairs and be downstairs and stand in line for the second bell to go in and wash your hands and face…You should see the girls coming down there—we had boots that laced up high and they’d tie them together and lace them when they got to the bottom. If you weren’t down there—up you would go to get the strap. They would give you the strap for being late—you were supposed to be down there when you were supposed to be.[1]

So began the daily regime at the Mount Elgin Residential School. The speaker is a former student who attended the school in the late 1920s and remembers well how cold she felt at night with only a few thin blankets to cover her, the antiseptic-smelling Lifebuoy soap, the strap—given for a variety of reasons, such as speaking her Oneida language—and the never-ending flights of stairs. At the same time, she recalls that “in a way when you look back it was good training.”

Many former students speak of both severe discipline and the usefulness of the practical skills learned. Others recall the loneliness they felt when away from home but also the more pleasant times, playing outdoors with friends, or the support and kindness of many of the teachers. Students also describe the innovative ways that children circumvented the institution’s rules—either by running away to their homes in local Chippewa, Munsee-Delaware, or Oneida communities, stealing food, or sneaking away in groups to speak their Indigenous languages.[2] Throughout the school’s history, students, parents, and First Nation councils wrote petitions, sent delegations, and hired lawyers to demand improved conditions for the children.

Establishment

The Mount Elgin Residential School was established in 1847 by an agreement between the Missionary Society of the Wesleyan Methodist Society and the Department of Indian Affairs. It opened formally in 1851, one of the first Residential Institutions in Canada.

Indigenous leaders in Ontario had lobbied for boarding schools as a way to educate their children to best take advantage of new economic and political opportunities. They wanted their children to acquire the academic skills necessary to participate in society on an equal footing with non-Indigenous people. Ojibwa leader Kahkewaquonaby (Rev. Peter Jones), who converted to Methodism, raised funds in Canada, England, and Scotland for such a school. He had expected the school to train girls and boys to become political leaders, missionaries, teachers, and interpreters, not domestic servants and farm hands. However, soon after its opening, when it became apparent that that Mount Elgin would not be operated by Christian Indigenous leaders as he had envisioned, Jones refused to send his own children there.[3]

Alongside Jones’ efforts, local Indigenous communities agreed in 1845 to set apart one-fourth of their annuities for the building and maintenance of industrial schools. The original sponsoring First Nations of Mount Elgin were the Chippewas of Sarnia (Aamjiwnaang First Nation), the Chippewas of the Thames, the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the Moravian of the Thames. These First Nations contributed a combined total of $2372 per annum until the school temporarily closed in 1862.[4] In later years, another $22,600 was allocated to the school from First Nation annuities without the affected First Nations’ consent.[5]

Initially only children from contributing communities were admitted to the school. By 1885, Mount Elgin accepted Indigenous children from across Ontario and from a number of communities in Quebec.

Curriculum

Conceived by the Methodists as a “manual labour school,” Mount Elgin’s curriculum comprised academic study, with heavy doses of manual training and household duties. According to an 1851 schedule, from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. the children spent seven and a half hours at physical labour and five and a half in the classroom.[6] The boys learned carpentry, shoemaking, wheelwright work, and blacksmithing. Girls were taught spinning, knitting, weaving, tailoring, and sewing. In addition, the boys helped construct new buildings and infrastructure, and the girls tailored nearly all student clothing and looked after the housework, cooking, baking, laundry, and milking. Industrial training was often more about the upkeep of the school than about learning. As younger and younger children attended Mount Elgin during its later years of operation, the problem of running such a large institution was exacerbated. As Principal Soper wrote in 1945, “It is impossible for babies of this age to feed, clothe and wash for themselves.”[7] Students were even kept in school past the obligatory age of sixteen “simply for the work they could do” both in the residence and on the farm.[8]

Farming

Mount Elgin included a 200-acre “model farm” where students grew wheat, oats, peas, millet, beans, corn, potatoes, mangel, and turnips, under the direction of an instructor. The school also rented up to 900 acres of pasture and haying lands from members of the Oneida of the Thames reserve. Stock comprised horses and cattle, including dairy cows that provided butter and milk for the school and heifers to be sold on the meat market. Pigs supplied the school with lard and pork. Older boys and girls stayed at the school during summer vacations, with pay, to attend to the animals and to bring in the harvest. Well into the 1930s, food from the farm, along with farm produce sold, accounted for approximately half the school’s budget.

At times, principals appeared more concerned about the farm than any other aspect of the school. Parents frequently objected to the farm labour expected of their children. In 1884, four students were expelled after protesting that “too much work is imposed upon us so that our tuition is limited to only about seventeen hours per week.”[9] Similarly, an 1894 resolution by the Chippewas of the Thames Council charged that the students worked too hard and that the Methodist Society was making a profit from their children. Farming, being crucial to the school’s operation, continued until Mount Elgin’s closure in 1946.

Running Away

Church and government officials were often concerned that Mount Elgin’s proximity to Indigenous communities interfered with the school’s program to “civilize” and Christianize. A 1908 investigation following the deaths of two students from tuberculosis concluded that Mount Elgin’s main problem was that the children were too close to their parents: “They meet their parents at Church every Sunday…While I was there parents came asking permission to see their children. They join them in the play ground and in fact are hanging around the neighbourhood more or less all the time.”[10]

Such close contact led to other difficulties for the school as well, among them, truancy. One former student explains, “We got caught—we weren’t really hiding anyway. We were just over here [on the Oneida reserve]—we had no intentions of going anyplace—this was our home.”[11] Children from other communities ranged farther afield when they ran away. The RCMP returned children from nearby Melbourne as well as from Sarnia, the Six Nations reserve near Brantford, and Niagara Falls. Pursuit stopped only at the international border, in cases where students crossed into the United States.[12] By the 1930s truancy had become rampant: on a single day in 1937, twenty-two students abandoned the school, and from 1938 to 1941 at least 17 children ran away each year.[13] When children did run away, their parents often resisted attempts to have them returned, frequently with the backing of their First Nation council.[14]

School runaways and concerned parents often cited poor conditions and overwork of the students in their criticisms of the school. In 1943, the Council of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation presented five sworn statements detailing poor diet and spoiled food, lack of medical care, severe strapping and physical abuse, and inadequate winter clothing.[15] A man who wrote to the school after his employee’s son ran away observed, “Glad I wasn’t born an Indian if I had to be a boy at Mount Elgin Institute.”[16] For their part, many parents wrote letters, visited school authorities, sought the backing of their First Nation councils, and even contracted legal assistance in their efforts to have authorities right what they considered wrongs committed against their children.

School Closing

Church authorities were faced with running a very large and old institution on a limited budget and with few staff. The consequences of such limitations put children’s health and safety at risk and were sometimes deadly. In 1901, contaminated water caused the death of the foreman’s wife and, in later years, several children injured themselves with the laundry’s mangle, which was outdated and in need of replacement. Throughout the school’s history, fire escapes were kept padlocked to prevent runaways. The various government inspectors also highlighted insufficient ventilation, lack of adequate bathing and toilet facilities, and unsafe structures. In a 1942 report, the superintendent of Welfare and Training described Mount Elgin’s buildings as “the most dilapidated structures that I have ever inspected.” In 1945, Principal Soper wrote: “There are a great many things about conditions around this building, and conditions under which little children have to live, which if printed and publicized would cause such a furore of indignation that someone would have to take cognizance of it, and that immediately.”[17]

By the early 1940s, the school building was falling apart and would require an estimated $200,000 to rebuild, funds difficult to expend due to wartime shortages. With enrolment down to 100 in 1944, per capita grants were insufficient to continue operations without relying excessively on the labour of students—65 of them under the age of 13.[18] It was also becoming increasingly difficult to recruit students: First Nations parents preferred to keep their children home and send them to day schools, post-war prosperity was drawing older students into the work force, and Indian Agents were reluctant to send children to the school because of its bad reputation.

Department of Indian Affairs officials started calling for Mount Elgin’s closure, and despite Church opposition, at the end of June 1946, the school was closed. The United Church auctioned off the farm implements and animals, using the proceeds to pay its overdraft at the bank.[19] Mount Elgin’s land holdings—547 acres at the time of the school’s closure—reverted to the Caradoc Indian Agency. A new day school opened on the reserve on November 1, 1946.

Footnotes

- Cited in Elizabeth Graham, ed., The Mush Hole: Life at Two Indian Residential Schools (Waterloo, ON: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 436. ↩

- Ibid., 427–480. ↩

- Donald B. Smith, Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 214, 240; and Robert Carey, “Aboriginal Residential Schools before Confederation: The Early Experience,” CCHA Historical Studies 61 (1995): 39. ↩

- L. Vankoughnet, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), to Sir John A. MacDonald, SGIA, Jan. 26, 1880, RG10, vol. 2046, file 9212, pt. 1, Library and Archives of Canada (LAC). ↩

- Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual report, 1896, p. 568; Order-in-Council, Feb. 13, 1900, RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-5, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada, Missionary Society Report (1851): xi-xii. ↩

- S.H. Soper to J.C. Bush, Sept. 19 1945, RG10, vol. 6208, file 468-5, pt. 10, LAC. ↩

- S.R. McVitty to A. Sutherland, Methodist Church of Canada, Dec. 10, 1909, RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Joseph White et al, petition, July 15, 1884, RG10, vol. 2269, file 53,978, LAC. ↩

- [illeg.], Superintendent, to Secretary, DIA, July 16, 1908, RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Quoted in Graham, Mushhole, 440. ↩

- See RCMP reports for 1938 through 1941 in RG10, vol. 6209, file 468-10, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- [illeg.], RCMP report, “Abbie Schuyler et al,” Sept. 27, 1937, RG10, vol. 6209, file 468-10, pt. 2, LAC; and RCMP reports for 1938 through 1941. ↩

- See, for example, Sutherland to Secretary, DIA, Dec. 3, 1904, and F.W. Jacob, to F.A. Macrae, Aug. 9, 1906, both in RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-5, pt. 1, LAC; F.W. Luffnell, Indian Agent, to Secretary, Indian Affairs Branch, July 12, 1940, RG10, [vol. 6209, file 468-10, pt. 2?], LAC. ↩

- George Down, Indian Agent, “Resolution No. 1 Chippewa of the Thames,” June 24, 1943, RG10, vol. 6209, file 468-10, pt.3, LAC. ↩

- R.W. MacDonald to DIA, Jan. 17, 1944, RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-1, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- Soper to Secretary, DIA, Oct. 15, 1945, RG10, vol. 6208, file 468-5, pt. 10, LAC. ↩

- R.A. Hoey, Superintendent of Welfare Training, to H.W. McGill, Deputy SGIA, Nov. 9, 1942, RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-1, pt. 3, LAC; Soper to Hoey, Sept. 18, 1944, RG10, vol. 6205, file 468-1, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- Berthe to McCutcheon, May 29, 1946, RG10, vol. 6210, file 468-24, pt. 1, LAC. ↩