McDougall Orphanage and Morley Residential School

McDougall Orphanage and Morley Residential School Timeline

Dates of Operation

1883–1908 (McDougall Orphanage and Training School); 1922–1926 (temporary semi-boarding school); 1926–1969 (Morley Residential School)

The McDougall Orphanage was administered by the Methodist Missionary Society and the Morley Residential School was managed by the Board of Home Missions for the United Church of Canada.

Location

The McDougall Orphanage was located in Morleyville, Alberta, on the north side of the Bow River, just east of the Stoney First Nation Reserve and approximately 40 miles west of Calgary. Morley Residential School was located on the reserve on the south side of the Bow River, near Morley, Alberta.

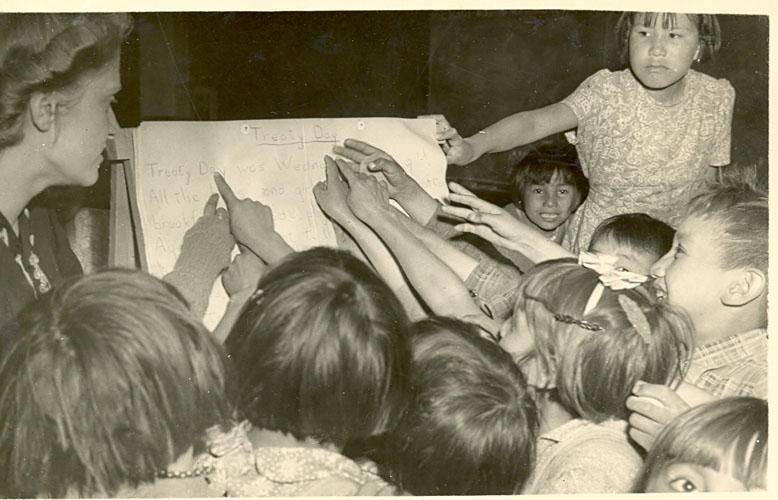

In 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot, Blood, Piikani, Sarcee and Stoney nations negotiated Treaty No. 7 (known as the Blackfoot Treaty) with the Canadian government. The Blackfoot confederacy hoped to prevent settlers, whisky traders, and Métis hunters from entering their territories. Like other First Nations of the plains, they also wanted to take up farming and cattle ranching to counter economic hardship and severe food shortages caused by dwindling buffalo herds. The treaty promised, among other things, that the government would pay the salaries of teachers to instruct the children of the signing First Nations.[1] From these early years, First Nations in the region strove to acquire schooling for their children. In the case of the Stoney, whose children would eventually attend Morley Residential School, parents lobbied repeatedly to have day schools in their communities in fulfillment of their treaty rights.

McDougall Orphanage and Day Schools

Treaty 7 established a reserve for the Stoneys (made up of the Wesley, Bearspaw and Chiniki First Nations) on the upper Bow River where the Methodist missionary George McDougall and his son John had established a mission and a day school in 1873. Around 1880, with some 43 children attending the day school, John McDougall began to board schoolchildren in his home. Stoney parents were amenable to this arrangement because they left the reserve for three months every year to hunt and they wanted their children to obtain an English education that would enable them to take advantage of new opportunities.

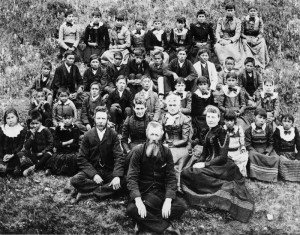

The Missionary Society, for its part, hoped to remove Indigenous children from the “contaminating” influence of their families and culture, “especially during the formative years of life,” in order to more easily instill in them Christian ways. [2] McDougall’s “orphanage” soon received assistance from the Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) and in 1883 opened officially as the McDougall Orphanage and Training School, under the administration of the Methodist Missionary Society. The 15 children in residence attended the day school for their classes. [3] Both the orphanage and the day school were located in Morleyville, on the north side of the Bow River.

In 1885, a second day school opened—on the river’s south side—to serve the children from the Bearspaw and Chiniki bands who could not reach Morleyville during the summer months. The school started in the house of the Bearspaw chief and was later moved into a schoolhouse built for the purpose. The teacher there, E.R. Steinhauer, was the son of the Chippewa missionary Henry Bird Steinhauer. [4] It appears that the Stoney preferred this set up—two day schools, one north and one south of the river—since they petitioned again and again to return to it after the McDougall orphanage expanded and the day schools were closed.

The Methodist Society, however, had other ideas. In 1885, they received government funding for the orphanage and the next year, a government grant of nearly 1,200 acres of land, some 8 kilometres closer to the reserve, for its exclusive use. [5] They established a new residence on the land and recruited their boarders from the day school. In 1890, a larger building, with room for 40 students, was erected. The old residence continued to serve as a carpentry workshop for the boys. In 1895 a separate schoolhouse was built behind the residence.

Meanwhile the days schools struggled on. Department of Indian Affairs officials reported irregular attendance and problems in retaining staff, but also observed, in 1895, “Where in former years the school was never considered in selecting [the Stoneys’] camping places, this year it is, the majority of them camping near their respective schools.” [6] By 1898, however, the day schools were “practically closed.” [7] The Morleyville school reopened briefly in 1902, but the Methodist Society opposed it: “It was the distinct understanding between us and the Department that when the new building for a Boarding School was erected, the day schools on the Reserve would be closed.” [8]

Curriculum at the McDougall Orphanage

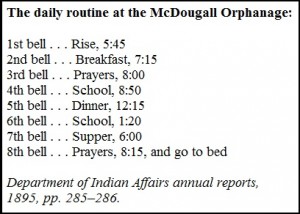

Children at the McDougall Orphanage had their vocational training in the morning and academic classes in the afternoon. By preference, the school took younger children because, according to the WMS, “the best results are achieved with children who enter before they are ten years old.” [9] At the same time, officials acknowledged that adjustment to school regimentation was not easy. “They find a great change from the wild, free camp life,” observed the WMS. [10]

Vocational training was organized along Western ideas of appropriate gender roles. For the boys, a great part of their time was dedicated to the farm and ranch. “The boys are taught that outside labor is men’s work, and that the men should allow the women to have their time to thoroughly attend to household affairs,” the WMS wrote.[11] The large grant of land the school had received was not well suited to agriculture, however. In 1894, the oat crop failed, and gophers destroyed the garden.[12] The following year, the DIA inspector reported that the schoolboys had killed 4,000 gophers, “but it seemed to have little effect in stopping the ravages of these pests.”[13] In 1896, the crop failed again, due to drought.[14] Later reports by the school’s principals noted simply that “owing to our nearness to the mountains, no farming can be done further than the growing of a quantity of green feed for stock, and a small quantity of vegetables.”[15]

The focus of the farm became the livestock, as did the focus of the boys’ training. In 1894, they cared for 52 head of cattle, nine sheep and lambs, and 12 horses, and they put up 20 tons of hay.[16] In later years, the number of milk cows increased and the sheep were replaced by pigs. The boys who worked on the ranch were taught teaming, ploughing, fencing, mowing, milking and the care of stock. But, as the principals noted repeatedly, the boys were small—in 1902, only three were over 14—and unable to do heavy work.[17]

Girls at the school were taught dairying (milking and butter-making), but otherwise their training consisted of domestic chores: sewing, knitting, mending, cooking, baking, washing and ironing. For a period, the boys learned blacksmithing in addition to ranch work.

Closure of the Orphanage

In 1905, the DIA audited the orphanage and discovered it was deeply in debt. The audit found that Principal Niddrie had been “entertaining” the schoolchildren’s parents when they visited the school and providing them with supplies to take home as a kind of bribe to keep their children there. Niddrie had also granted the students weekly overnight visits home.[18] In addition, Church officials charged that Niddrie had “practically gone native,” living and cooking in a shack—behaviour, in their view, that did not constitute a model of proper Christian living.[19] Niddrie was dismissed, leading to friction and resignations among the staff and a full-out boycott by Stoney parents.

Over the next three years, school officials tried to woo the community by providing them with greater access to their children and allowing overnight visits, but Stoney opposition to the new management continued. “The agent, I know, has done what he could to induce the parents to send their children to the Orphanage, but with indifferent success,” the Indian commissioner reported.[20] In October 1908, the school inspector found only four children in residence and was told that “soon there will be none.”[21] The Missionary Society was furious. “It is an outrage to allow these people in their ignorance to hold up a well-equipped institution when it exists for the express purpose to educate and elevate them,” wrote Thomas Ferrier, of the Board of Missions.[22]

In November 1908, the orphanage staff resigned, leaving without lodging the 17 children in residence whose parents were away. The Missionary Society transferred the children to Red Deer Residential School.[23] Martin Benson, of the DIA’s Schools Division, observed with some irony, “The days schools were closed in the first instance to help the orphanage but the orphanage closed itself through mismanagement.”[24]

Stoney parents immediately lobbied for two day schools, but only one school was reopened in the hospital on the north side of the river. The community did not support the decision. “We will have nothing to do with the Morley hospital as a day school,” read a petition from Stoney parents.[25] Once again, the day school struggled, closing within the year, reopening in 1909 and closing again in 1910. The school was not well located for many Stoney parents, but the DIA would not issue funds for building elsewhere. DIA and church officials pushed again for establishing a residential school, but the Stoneys resisted, citing their treaty right to a school in each of their communities.

The Indian Agent described the impasse: “Another reason against [the residential school] is that the Indians absolutely refuse to sign away their probable right to a day school.”[26] Another official was frustrated that the Indians “wanted the old slip-shod, ‘go as you pleases’ school as in the old days” but happy that they were all supportive of providing an education for their children.[27] In the meantime, the chiefs and councillors of the Wesley, Chiniki, and Bearspaw First Nations agreed that if a modern, well-equipped residential school was built, they would send their children and encourage others to do so as well.[28] For the next decade, however, the 300 children of the Stoney reserve had no school available to them at all.

Morley Residential School

In October 1922, a temporary semi-residential school was set up by the Methodist Church, with government support, until funds could be found for a permanent school. The residence was located in the hospital that had served as the day school, and the classroom was located in the Methodist church, also on the reserve. The school boarded 12 to 15 students, and other children attended as day students. A teacher began work in January 1923. In 1926 this temporary arrangement was supplanted by a permanent residential school.

In 1926, the Morley Residential School, with a new residence building to accommodate up to 60 students, opened its doors. The building, which was located southwest of the hospital on the Stoney reserve, was built and owned by the government but managed by the United Church. Classes continued to take place in the church because there were no provisions for classrooms in the residence building.

Morley Residential School expanded over the years (as did enrolment), with a two-classroom block opened in 1929, an addition to the residence in 1935, a four-classroom block with teachers’ quarters built in 1955 and a four-classroom addition to that block in 1967. The resident population peaked at 95 in 1940, but attendance at the school, which also received day students from 1929 until at least 1938 and again from 1953 until the residence closed in 1969, grew steadily to 295.

The residence was only large enough to accept approximately half the school-age children on the reserve, a situation that had not changed significantly by 1951, when the agency superintendent complained, “There are many children on this reserve for whom no accommodation exists and their number are increasing. We seem to be getting nowhere with education on this reserve.”[29] Overcrowding led the principal, in 1931, to provide beds for five girls in his residence.[30] The addition in 1951 of a separate day school—the David Bearspaw Day School—and its amalgamation with the residential school in 1954 appears to have alleviated this problem. By 1962, the head of the DIA’s Education Division was able to report that “all of the Stony [sic] children between the ages of 6 and 15 years are in school.”[31] After amalgamation all five teachers at Morley were paid by the Department of Education rather than the United Church.[32]

The principal exception to enrolment from the Stoney reserve was a number of children from the Crooked Lake and Qu’Appelle agencies of Saskatchewan who attended Morley Residential School in 1960 and 1961. After the United Church closed its residential schools in the neighbouring province, Principal Ron Campbell and United Church officials worked to bring these students to Morley or Edmonton Residential School rather than allow them to go to Roman Catholic schools in their home province. In defiance of government directives to the contrary, Campbell continued this practice until June 1961, when the government cancelled all admissions from Saskatchewan.[33]

From 1963 to 1968 (at least), Morley also accepted a small number of children from the Sunchild and Sarcee bands, perhaps because fewer and fewer local children were interested in the residence. By that time, the Morley residence was used principally for high school students who were bussed from there to local high schools.

Curriculum at Morley Residential School

When the residential school first opened, all the students, because they had been without schooling until then, entered the first grade. Higher grades were added successively as the children advanced in their studies. Kindergarten and “terminal” classes “for older pupils that were not making a successful academic program” were added by early 1958.[34] Grade 9 was offered in 1959 and again from 1963 to 1966 after initial attempts to integrate high school students at schools in Cochrane and Calgary foundered because many students found the transition difficult, due in part to racism at the schools.[35] In addition to academic study, Morley Residential School was to provide vocational training in carpentry and blacksmithing to boys, and domestic arts to girls, as well as farming. The Indian Agent’s reports for 1929 indicate that vocational instruction comprised cooking, laundry, sewing, farming, gardening, poultry raising, livestock care, blacksmithing and carpentry.[36]

Morley Residential School opened on the half-day system, with half the children’s time spent in the classroom and half on chores or vocational work. By 1953, however, all the pupils attended school full time.[37] Initially the manual work load was not, in the opinion of visiting inspectors, particularly onerous. In 1935, one wrote, “Very little outside work is carried on here with the exception of farming a few acres for green feed, putting in a garden, etc., and as I have often mentioned before, it is only about one year in 6 or 7 that their potato crop is a success.”

The school grew other root vegetables successfully that year and kept 30 head of dairy cattle, for milk and butter, six horses, ten pigs and “a few chickens.”[38] In 1939, after principals at a number of schools proposed that students gain experience in feeding and raising fur-bearing animals, a mink farm was introduced, which operated until 1952.[39] An auditor reported in 1950 that the school had 1,050 acres for its use (100 acres “at the school,” 800 acres of Crown land and 150 acres of church land), of which all but 10 acres under cultivation (25 in 1952) was dedicated to pasturage.[40] All farming ceased in 1958 and the proceeds from selling off equipment and stock went to the United Church.

The balance between vocational work and chores, on the one hand, and academic work, on the other, shifted considerably as staff became short during and immediately following World War II. By 1946, parents were protesting that some senior students were getting no classroom time at all: “I asked one of the older girl pupils, ‘Are you getting proper education?’ She answered, ‘No.’ She also said ‘We older girls have never been in the class rooms for two years.’”[41] At the time, Morley had no classroom teachers on staff, so academic instruction was divvied up among the principal, the matron and the seamstress. And although the workshop was well equipped, the boys were not receiving training. The Indian Agent noted that it was not possible to get staff for the low wages offered.[42]

In 1951, the superintendent of the Stoney/Sarcee Indian Agency wrote, “I should like to see classes in Manual Training and Household Economics started here, along with organized sports and physical recreation. However, the senior boys and girls are already spending too much time away from the classroom attending to their chores and household duties.”[43] Manual training for boys was not reinstituted until 1954. For girls, in addition to housework, kitchen work and sewing and mending clothes, from 1939 to 1946 local women gave them leather and beadwork instruction. Indigenous craft instruction was reintroduced in 1968.

Conditions and Allegations of Mistreatment and Abuse

As at other residential schools, poor clothing and food were cited by parents and students at Morley Residential School who were unhappy with conditions there. Given the extreme winter weather, proper clothing was of vital importance: “The children are not well dressed. If we don’t look after our children, they will freeze,” one parent declared; “When it is cold she comes home half frozen,” said another.[44] Overcrowding was sometimes an issue and, for much of its existence, Morley Residential School completely failed to meet the educational needs of the Stoney reserve.

When Rev. George Dorey visited the school in 1947 and met with class leaders Thomas Snow and John Hunter, he learned that the children wanted more time in the classroom, more teachers, and a day school so they could live at home. Parents demanded less work for their children and more holiday time, and they wanted to receive the family allowances, denied to parents of boarders, so they could equip their children with better clothing. Dorey, however, discounted these grievances and considered the meeting simply an opportunity for the Stoney “to pour out all their troubles—which could be summed up in this way—that they want more of everything, and they are not very anxious to co-operate with either the Church or the Government.”[45]

Beyond these shortcomings, the overwhelming majority of complaints stemmed from allegations of severe corporal punishment, physical abuse, and from time to time suggestions of—and one conviction for—sexual abuse. In many cases, community members hired lawyers and lobbied government and church officials to halt mistreatment. The students also protested actions they considered unjust. For example, in May 1953 all 32 boys abandoned the school after severe disciplinary action by the matron.[46]

Closing of the Residence

In 1946 the Indian Association of Alberta, with the approval of the Stoney Band Council, submitted to a joint committee of the House of Commons and the Senate a report recommending a day school at Morley. Five years later they got one. The David Bearspaw Day School opened with 30 students, grew to 69 after amalgamating with Morley Residential School, and kept growing just as surely as the resident portion of the school population continued to shrink. Parents generally preferred the day school arrangement, and above all, did not want their children sent away from the reserve. By 1961, only 39 students were in residence at Morley: 27 were attending high schools in Calgary; 8 were orphans; and four did not have bus routes available to them yet.[47] By 1968, the number of resident students was 13. On several occasions (from 1951 on), the Department of Indian Affairs recommended closing the Morley residence—citing among other things the comparatively cheaper cost of day schools—but the difficulty of accommodating the small pool of children that still required housing, as well as resistance from the United Church, postponed closure until 1969.

Footnotes

- Treaty and Supplementary Treaty Number 7; Richard Price, ed., The Spirit of the Alberta Indian Treaties (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1999); and Treaty 7 Elders and Tribal Council, with Walter Hildebrandt, Sarah Carter, and Dorothy First Rider, The True Spirit and Original Intent of Treaty Seven (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996). ↩

- A. Sutherland, General Secretary, Methodist Missionary Society, to Deputy Secretary General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), Feb. 4, 1904, RG10, vol. 6338, file 700-1, pt. 1, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). ↩

- H.L. Platt, “McDougall Orphanage,” ch. 4 in The Story of the Years: a History of the Woman’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, Canada, from 1881 to 1906 (n.p.: [Women’s Missionary Society Methodist Church Canada], 1908), vol. 1, pp. 49–50.

- “Stoney Reserve, Morley,” Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual report, 1881, pp. xxix–xxx; “Stoney Reserve Day Schools (Methodist),” DIA annual report, 1888, pp. 142–143. ↩

- Platt, “McDougall Orphanage,” p. 49; DIA annual report, 1887, pp. 185–187. ↩

- P.L. Grasse, farmer in charge, to SGIA, June 30, 1896, DIA annual report, 1896, pp. 203–204. ↩

- E.J. Bangs, farmer in charge, to SGIA, Aug.31, 1898, DIA annual report, 1898, pp. 168–169. ↩

- Sutherland to Deputy SGIA, Feb. 4, 1904. ↩

- Platt, “McDougall Orphanage,” 52. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 53. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1894, pp. 124–125. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1895, pp. 285–286. ↩

- J.W. Butler principal, to SGIA, Sept. 1, 1896, DIA annual report, 1896, pp. 237–238. ↩

- John W. Niddrie, principal, to SGIA, July 24, 1901, DIA annual report, 1901, pp. 348–349. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1894, pp. 124–125. ↩

- Niddrie to SGIA, June 30, 1902, DIA annual report, 1902, pp. 344–346. ↩

- David Laird, Indian Commissioner, to Secretary, DIA, Mar. 27, 1906, RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- citation to come ↩

- Laird to Secretary, DIA, Aug. 22, 1907, RG10, vol. 6338, file 700-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Martin Benson to Deputy SGIA, Oct. 14, 1908, RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Thomas Ferrier to Sutherland, Secretary General of Missions, Mar. 21, 1906, RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ferrier to Hon. F. Oliver, telegram, Nov. [9?], 1908, and Frank Pedley, Deputy SGIA, to Ferrier, telegram, Nov. 10, 1908, both in RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Benson to Pedley, Jan. 5, 1912, RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Amos Bigstony et al to the Indian Department, Dec. 27, 1909, RG10, vol. 6338, file 700-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- J.W. Coaddy, Indian Agent, to Secretary, DIA, Oct. 19, 1912, RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. The agent added the word probable only after typing up his letter.↩

- J.D. Lafferty to D.C. Scott, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, July 23, 1909, RG10, vol. 6338, file 700-1, LAC. ↩

- Chief Peter Wesley et al, “Regarding the proposed school . . . ,” Oct. 7, 1912, RG10, vol. 6355, file 757-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Extract from Indian Superintendent R.F. Battle’s Quarterly Report for the quarter ended June 30th, 1951, regarding the Stony/Sarcee Agency,” RG10, vol. 8672, file 772/6-1-010, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Inspector Christianson to W.M. Graham, Indian Commissioner, Jan. 14, 1931, vol. 6356, vol. 757-5, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- R.F. Davey, Chief, Education Division, to Catherine Sinclair, Assistant Editor, Chatelaine, Mar. 15, 1962, RG10, vol. 8758, file 772/25-1-010, LAC. ↩

- Davey to E.A. Robertson, Acting Regional Supervisor of Indian Agencies, May 17, 1954, RG10, vol. 8758), file 772/25-1-010, LAC. ↩

- Gooderham, District Superintendent of Indian Schools, to Regional Supervisor, Alberta, Sept. 29, 1960, and L.C. Hunter, Regional Supervisor, Alberta, to Chief, Education Division, Ottawa, Sept. 30, 1960, both in RG10, vol. 8753, file 601/25-1, pt. 2, LAC; N.J. McLeod, Regional Supervisor, Saskatchewan, to Regional Supervisor, Alberta, Mar. 17, 1961, (205) 701/25-2, vol. 1 (12/58–02/69), LAC. ↩

- J.E. Kempling, Principal, “Morley Indian Residential School, United Church of Canada; Annual Report,” access. no. 1983-050C, box 11, file 1, United Church of Canada Archives (UCCA). ↩

- Ragan to Davey, Nov. 2, 1967, file 772/6-1-010, pt. 8 (1966–1972), [Indian and Northern Affairs Canada]. See also Hunter to Assistant Director (Education), July 10, 1964, file 772/25-1-010, pt. 2 (06/61–07/68) [INAC]; and Assistant, Morley Indian Reserve, to Superintendent, Stoney/Sarcee Indian Agency, “Semi-annual Report—Stony [sic] Reserves, April 1, 1964, to October 1, 1964,” Sept. 25, 1964, file 772/3-8, pt. 4 (04/65–02/70), [INAC]. ↩

- R. Hinton, Indian Agent, reports for May and June 1929, file 772/23-5-010, pt. 1 (1894–1966), [INAC]. ↩

- Hugh McPhail, principal, “Indian Residential School Quarterly Return,” file 772/23-26-010, pt. 1 (03/53–10/68), [INAC]. ↩

- Unknown inspector to Dr. Harold W. McGill, Deputy SGIA, Mar. 23, 1935, file 772/23-5-010, pt. 1 (1894–1966), [INAC]. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1939, p. 223. ↩

- H.G. Chariton, Regional Administrator, Office of the Comptroller of the Treasury, to W. Lauchlan, Chief Treasury Office, Indian Affairs Branch, June 2, 1950, and Oct. 10, 1952, RG10, vol. 8843, file 772/16-2-010, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- J.N.R. Iredale, Acting Indian Agent, council meeting minutes, Oct. 15, 1946, vol. 6358, file 757-10 pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Iredale to Indian Affairs Branch, Nov. 12, 1946, RG10, vol. 6358, file 757-10, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Battle to Gooderham, Mar. 9, 1951, RG10. vol. 8758, file 772/25-1-010, LAC. ↩

- “Statements given to Mr. Wild on February 28, 1951, re Morley Indian Residential School,” RG10, vol. 8758, file 772/25-1-010, LAC. ↩

- George Dorey, Secretary of the Board of Home Missions, “Memo re. Morley Indian Residential School,” March 24, 1947, access. 1983.050C, box 28, file 474, UCCA. ↩

- “Principal’s Monthly Report—Morley Residential,” May 1953, file 772/23-16-010, pt. 1 (05/53–06/68), [INAC]. ↩

- Hunter to Indian Affairs Branch, Nov. 6, 1961, file 772/25-1-010, pt. 2 (06/61–07/68), [INAC]. ↩