File Hills Residential School

Dates of Operation

1889–1949

Operated by the Women’s Missionary Society of The Presbyterian Church in Canada and, after 1925, by the United Church of Canada.

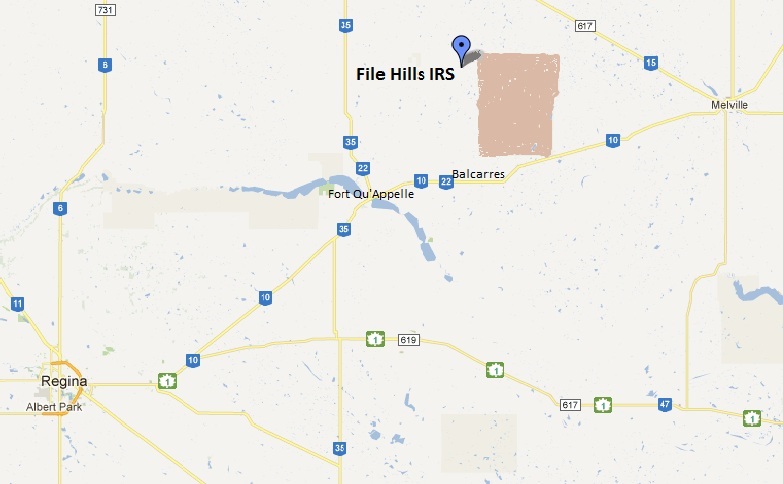

Location

Approximately 14 kilometres north of Balcarres, Saskatchewan, and 100 kilometres northeast of Regina, just outside the western boundary of the Okanese reserves. After the school closed in 1949, the site became part of the Okanese reserve.

The meals were not bad although we never got enough to eat, especially when we had to work half a day, sawing wood, cleaning barns, digging potatoes, any kind of harvesting and planting. We used to steal anything to eat, we’d even run for miles on a Saturday afternoon to raid homes for a bit of food…On Saturday afternoons we’d slip over the page wire fence to hunt rabbits or partridge, we would then have a feast with our kill. We used sling shots as our weapons which were strictly illegal. At times we would even eat grey squirrels. This was one of our fun times in school.[1]

—former student reflecting on his experience at File Hills Residential School in the 1930s.

In 1874, the Cree, Saulteaux, and Assiniboine peoples of what is now southern Saskatchewan negotiated Treaty No. 4 (also known as the Qu’Appelle Treaty) following the decline of game in their territories and increased Métis and white settlement in the region. The Indigenous signatories insisted in the treaty on protection of their traditional hunting and fishing practices, assistance with farming, annuities, and provisions for education. The treaty promised maintenance of “a school in the reserve allotted to each band as soon as they settle on said reserve and are prepared for a teacher.”[2] Indigenous people initially saw their children’s education as a means of acquiring new skills that would help them adjust to the changing economic and political order in the region.

Establishment

The File Hills Residential School began as a small day school, opened by J.C. Richardson in 1884 on the Little Black Bear Reserve. It closed soon afterwards, a failure one File Hills Residential School principal later attributed to lack of interest from the community in formal education and to the unsettled conditions in the region during the Riel Rebellions.[3] In September 1886, R. Toms reopened the day school, which operated until September 1889.

In 1889, the Women’s Missionary Society, with financial support from the Presbyterian Mission Board and the Department of Indian Affairs, built a large stone building outside the reserve’s boundaries, next to the Indian agency buildings. The school was three storeys high and measured 30 square feet. It included accommodation for the missionary, his family, and 25 children.

Principal Campbell hoped that the food and clothing the home supplied, which had been donated by the Ladies Foreign Mission Society, would induce local families to send their children.[4] Campbell, however, was disappointed; only eight students were registered when the school officially opened that fall. Indian Agent Reynolds was also discouraged by the general disinterest in the new school: “I regret to report that the Indians have not shown a more willing disposition to avail themselves of the excellent opportunities afforded them for sending their children to school. The average daily attendance for the year has been five.”[5]

School authorities initially focused enrolment efforts on Plains Cree children from the neighbouring Peepeekisis, Okanese, Star Blanket, and Little Black Bear Indian reserves of the File Hills agency. However, for many years, Chief Star Blanket and his community refused to send their children to File Hills Residential School. The school also recruited students from the Pasqua, Muscowpetung, and Piapot Indian reserves in the Qu’Appelle agency and from the Pelly and Duck Lake agencies, although parents from these communities protested that File Hills was too far from their homes and they demanded day schools in their communities in compliance with Treaty No. 4.[6]

Mr. Heron, the Presbyterian missionary responsible for recruiting to File Hills, was sympathetic to community demands for a day school, but Andrew S. Grant, Superintendent of Home Missions, pushed for more rigid enforcement of attendance: “It seems to me that, when the Government goes to the expense of building Boarding Schools and maintaining them, some pressure should be brought to bear upon Indian parents to insist on their giving a liberal education to their children.”[7] Church officials hoped the Indian Department would back, with force if necessary, their attempts to assimilate Indigenous children to “civilization” and to transform them from hunters into Christian farmers.

Over the years, attendance gradually increased from 16 students in 1899 to 24 in 1910, leading to the construction of a new, larger building. By 1924, enrollment had reached 80.

Curriculum and Farming

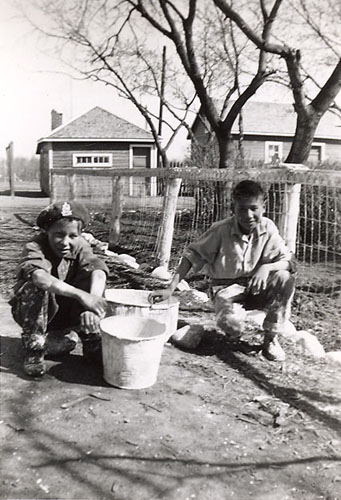

Farming and dairying were major activities at File Hills, especially for the boys. In 1900, the school owned 200 acres and had about four acres under cultivation with carrots, potatoes, turnips, and other vegetables. By 1908, the Church purchased an additional 200 acres. The land was largely bush, thickly wooded, and partially located on the bluffs, which made farming difficult and limited the area under cultivation. The crops failed for many years in the 1930s, as they did throughout Saskatchewan during the Depression. By 1940, the farm supported 35 head of cattle and many chickens. Operated primarily using the children’s labour, the farm produced potatoes, vegetables, milk, and butter for both school consumption and sale to the local community. The boys also cut all the wood for winter heating.

Girls were taught domestic skills—cooking, sewing, and general housework—with the aim of preparing them to become farming wives or domestic servants. Boys received vocational training in carpentry, painting, electrical engineering, and the maintenance of gas engines. Like many residential schools, File Hills operated on the half-day system, a schedule grade 8 student Myrtle Bean described this way in a 1930 letter to a Junior Red Cross in Indiana: “The Senior pupils attend school only half a day. Grade VII and VI go in the morning and Grade VIII in the afternoon. The other half day consists of cooking, washing, sewing and mending. The primary classes, from one to four, go both morning and afternoon.”[8] Also referring to this system, graduate Eleanor Dieter observed, “The students do not advance very rapidly in their grades as they attend school only half the day.”[9]

File Hills Colony

School administrators hoped that graduates would marry and take up land on the File Hills Colony, a planned Christian community established by Indian Affairs inspector William Morris in 1898 on the Peepeekisis reserve. When a boy from the residential school reached 16 or 17, he could choose an 80-acre farm in the colony and work the land under the supervision of the government farm inspector.

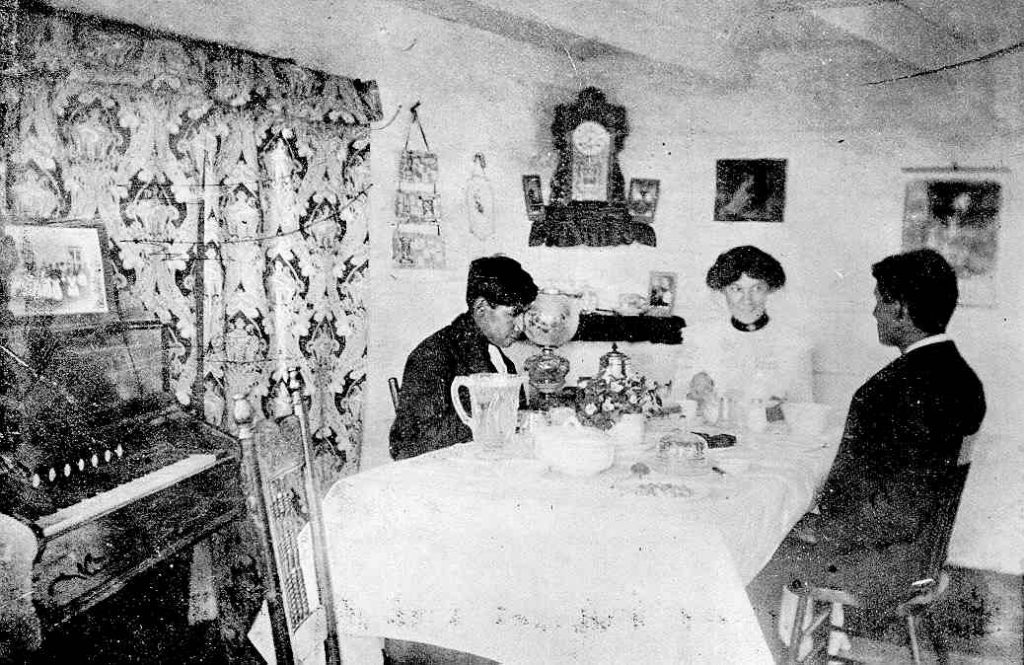

“In this way,” wrote Principal Kate Gillespie in 1904, “by the time a boy leaves the school he has made a very good start towards making a home for himself.”[10] The Church promoted the model community, “where you will see graduates from almost every school in the Northwest. You will see well-worked farms, prosperous looking buildings, well-kept live-stock. The women are good, clean housekeepers. In short, it is equal to any district of its age in the Province of Saskatchewan.”[11] For the Presbyterian Church, Christian marriages, productive farms, and clean, tidy homes marked school and colony success and “progress.”

The school’s administrators hoped that graduates wouldn’t “revert to old Indian habits” once they left school. However, it was difficult to maintain the farms because federal policy restricted Indigenous farmers to small-scale outfits that were unable to compete with larger farming operations in the region.[12] The colony closed in the mid-1930s, and by 1945 the Peepeekisis First Nation began to formally challenge the displacement of Peepeekisis community members that had occurred because farming land was transferred to individuals who were not band members.[13]

Community Relationships

One of the most frequent complaints lodged by parents against File Hills Residential School was that their children spent excessive time working on the school farm. In September 1913, Chief Ben Pasqua wrote that his two boys spent all their time herding sheep and tending cattle and never went to school. He requested a day school on his reserve.[14] Parents of students who ran away said that their children did no classwork because they were always outdoors hauling hay and cutting wood. In 1940, Wilfred Dieter ran away for the second time, because he was not receiving a proper education and his father wanted him to stay home.[15]

In September 1924, Inspector Graham suggested that the lack of sympathy and understanding on the part of the staff towards the children was the cause of truancy at the school: “If a little more kindness and less punishment were meted out to them, better results would be obtained.”[16] He observed that the children had no activities, sports, or games to occupy their time. In the 1920s, the school responded to such criticisms by broadening the range of outdoor activity with recreational opportunities and sports.

Some school events suggested more positive community-school interactions. In 1929, Principal Rhodes initiated weekly moving picture screenings that were attended by people from the different reserves. The screenings were “a source of great pleasure to the children of the school, and many of the older Indians have been in the habit of going there once a week and having a regular picture show in the outside classroom.”[17]

Student Health

For much of its history, the school was plagued with high levels of sickness, buildings in poor condition, overcrowding, and a shortage of staff. In 1922, Medical Inspector H.P. Bryce reported in The Story of a National Crime: Being an Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada, that 24 percent of all children who had attended residential schools in Canada had died. At File Hills, “75 percent were dead at the end of the 16 years since the school opened.”[18]

When Principal Gillespie reported the death of two girls under treatment at the school for tuberculosis in the winter of 1908, she blamed their dormitory, which was later condemned: “We fear the girls’ dormitory is largely responsible for disease among the girls. The boys, as a rule, are healthy.”[19] Between 1907 and 1910, the boys slept, summer and winter, in a tent on the school grounds.

School Closing

By 1948, File Hills Residential School was overcrowded and the building was considered a fire hazard. An inspection of the school’s plumbing revealed unsanitary bathrooms, contaminated milk, a laundry that was “a first class germ trip,” and a kitchen, dangerous to the heath. “A complete medical check up should be made of all inmates of the institution, and if repairs are not carried out, it would be criminal neglect,” reported the inspector.[20]

The Department of Indian Affairs recommended closing the school and establishing a day school on the site. United Church officials reluctantly agreed and on June 30, 1949, the school was closed. Children from the File Hills communities within walking distance attended the day school. Other students were sent to the United Church residential schools at Brandon or Portage la Prairie. By the late 1950s, the school buildings had been dismantled and the land sold off by the Crown Assets Disposal Corporation, with the exception of 101.93 acres, which were added to the Okanese First Nation.

Footnotes

- “Life in File Hills Residential School,” undated typescript, accession 2004.116C, box 11, file 14, United Church of Canada Archives (UCCA). ↩

- “Treaty No. Four.” ↩

- F. Rhodes, principal, “A Condensed History of the File Hills Residential School,” April 1939, accession 1998.027C, UCCA. ↩

- W.L. Reynolds, Indian Agent, to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), Aug. 1, 1889, Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual report (online), 1889. ↩

- Indian Agent Reynolds, 1890. ↩

- R.B. Heron to Rev. Dr. Grant, Nov. 13, 1913, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-1, pt. 1, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). ↩

- Andrew Grant, General Superintendent of Home Missions, to D.C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, Feb. 4, 1914, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “File Hills Indian Juniors of Saskatchewan Prepare Excellent Portfolio,” June 1930, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Address by Mrs. A.H. Brass (Eleanor Deiter), 50th Anniversary, June 14th 1939,” accession 1998.027C, roll 12, UCCA. ↩

- Kate Gillespie to SGIA, Aug. 30, 1904, DIA annual report (online), 1904. ↩

- W. Gibson, “File Hills Boarding School,” in The Missionary Messenger, undated clipping [c. 1916], in RG10, vol. 1393, LAC. ↩

- Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990). ↩

- In 1986, the Peepeekisis First Nation submitted a specific claim to the federal government disputing the validity of the land transfers. The claim is still under negotiation. See “Peepeekisis First Nation Inquiry: File Hills Colony Claim.” ↩

- Chief Ben Pasqua to unknown, Sept. 6, 1913, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- H. Christianson, General Superintendent of Agencies, to Rhodes, Oct. 28, 1940, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- W.H. Graham, Indian Commissioner, to Secretary, DIA, Sept. 24, 1924, RG10, vol. 9136, file 314-11, LAC. ↩

- Graham to Scott, Nov. 8, 1929, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-5, pt. 4, LAC; Rhodes to Graham, Nov. 5, 1929, RG10, vol. 6307, file 653-5, pt. 4, LAC. ↩

- P.H. Bryce, The Story of a National Crime: Being an Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada; the wards of the nation, our allies in the Revolutionary War, our brothers-in-arms in the Great War (Ottawa: James Hope and Sons, 1922), 4. This report was based on an earlier one published in 1907. ↩

- Gillespie to Deputy SGIA, Apr. 13, 1908, DIA annual report, 1908. ↩

- “Re. File Hills Residential School,” June 5, 1948, RG10, vol. 6308, file 653-5, pt. 4, LAC. ↩