Coqualeetza Residential School

Dates of Operation

1886–1894 (Coqualeetza Home); 1894–1940 (Coqualeetza Institute)

Operated jointly by the Women’s Missionary Society and the Board of Home Missions of the Methodist Church and, after 1925, by the United Church of Canada.

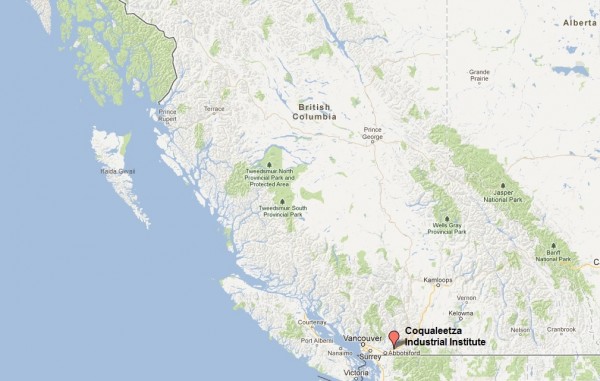

Location

On the shores of Luckakuck Creek in Sardis, British Columbia, about 5 kilometres south of Chilliwack, in the Fraser Valley.

I was rather terrified of the huge Indian youths who were difficult to control in class, and even more hard to manage at the breakfast table over which it was my duty to superintend…According to rule, Grace must be said before they sat down, but to silence them first was far from easy, and all through the meal they would be hurling cherry stones at the opposite table [where the girls sat]. There was always plenty of such ammunition for the tables were laden with fruit and the children generally, fed like fighting cocks.

—Rachel E. Large, who began teaching at Coqualeetza Institute in 1911 [1]

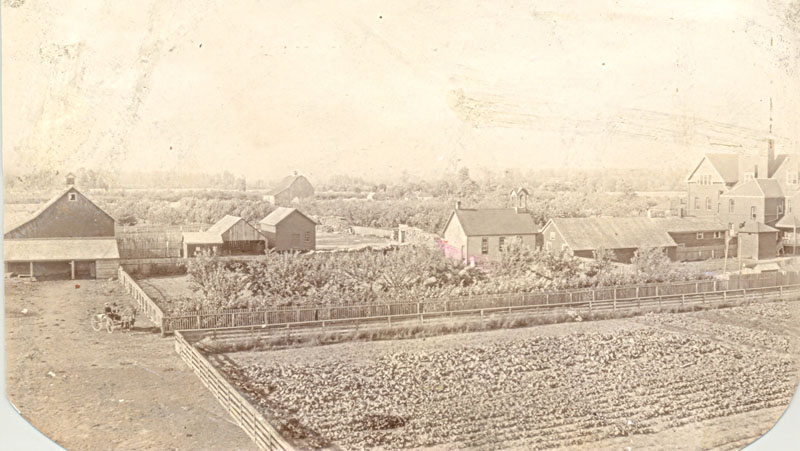

Establishment

In the late 1860s, Methodist missionary Thomas Crosby visited Coast Salish territory holding revival camps and vaccinating against smallpox, which was ravaging Indigenous communities across the province. Crosby established a church at Chilliwack that served both the Sto:lo First Nations of the Lower Fraser River and non-Indigenous settlers. [2] In 1877 the mission was taken over by Charles Montgomery Tate and his wife, Caroline, but in 1880, the couple was sent north to establish a mission among the Heiltsuk nation in Bella Bella. [3] By the time they returned in 1884, the Methodists had acquired land in Sardis, just south of Chilliwack in the traditional territory of the Skowkale First Nation, which would become the site for the permanent mission. The Tates opened a day school in their house, but because the Sto:lo travelled widely to work in a number of industries, including hop farms south of the border, the school was “alternately full and empty, without notice given.” [4] The Tates decided to convert part of their home into a boarding school: “A partition was removed, and the room thus enlarged became school-room, dining-room and work-room, while at night it served as sleeping-room for the boys.” [5] Like other missionaries, they believed that removal of children from the influence of their homes and families was the best way to achieve cultural change. Eight children were enrolled, many of them orphans or girls estranged from their communities.[6]

In the following year, the Women’s Missionary Society provided a grant to assist in this work, and a teacher was employed. As local support and enrolment for the school grew, the Women’s Missionary Society financed construction of a separate school building with accommodation for 40 students. By the time the Coqualeetza Home, as it was called, opened in 1890, there were 28 children in attendance.[7] The name Coqualeetza was an anglicized form of the Halkomelem word Kw’eqwalith’a, the name of the Sto:lo fishing site on Luckakuck Creek where the Home was erected. In Sto:lo tradition the word refers to women beating blankets at the site, an act the Methodists interpreted as one of cleansing, a notion they emphasized in their descriptions of educational work in Sardis.[8]

On November 30, 1891, with the Home filled to capacity and the Women’s Missionary Society considering ways of replacing or enlarging it, a lamp exploded on the second floor and the building burned to the ground.[9] The teachers and about half the children were moved into the mission house and the rest were sent home. With insurance on the building and a grant from the General Board of Missions, the Women’s Missionary Society was able to rebuild, a process that took two years to complete. In the meantime, a temporary day school was erected and classes continued.

Built to house 100 boarders and eight to ten staff, the new Coqualeetza Residential School opened its doors on April 26, 1894. It was the largest residential school in the province, with some 63 students in attendance on the day it opened. Despite this, the government agreed to finance no more than 50 children. Prison labour had made the children’s cots, and women from church congregations in central Canada, their quilts. The Superintendent of Indian Affairs and representatives of Indigenous nations attended the opening ceremonies. Indigenous leaders took advantage of the gathering to present a petition, read aloud by Principal Tate, calling on the government to uphold their fishing rights and to stop destruction of their fisheries.[10] The Women’s Missionary Society continued to help finance the school, but management was turned over to the Methodist Mission Board.[11]

In the winter of 1906, the primary classroom burned down and was not replaced.[12] Instead, in 1910, the government provided a grant for two tent dormitories, one of which was used for the boys while the other served as the primary school classroom until another tent dormitory was added in 1915. Open-air dorms were cheaper to install, but they were also thought to provide a healthier, better ventilated environment for the children and to aid in the prevention of tuberculosis. As Mission Board representative Thomas Ferrier remarked, “These building cannot be surpassed in the British Columbia climate for comfort, fresh air, and sanitary conditions.”[13]

Farm

In addition to the school building, Coqualeetza Residential School operated a small farm, with 20 acres under cultivation at the time of its opening. Situated in an extremely fertile valley, the farm, though smaller than those of residential schools in other parts of the country, provided a wide variety of fresh produce for the institute’s use. In this period, the farm was also the focus of the children’s vocational training. “In accordance with the policy of the Indian Department, the first place is given to farm and garden work,” Principal Joseph Hall wrote in 1899.[14] Girls and boys had separate gardens, the girl’s being used to raise flowers as well as vegetables. Hall aimed to train the boys to become commercial rather than subsistence farmers as a way to become “qualified for citizenship.”[15]

In 1899, the Mission Board bought 70 acres adjoining the school property and leased it to the institute. By 1903, the garden was yielding almost 600 pounds in small fruits, 200 pounds of rhubarb, as well as lettuce, radish, garden turnips, peas and other summer vegetables. There was an orchard that produced more than half a ton of cherries and plums and more than a ton of apples. The grain crop comprised nearly 18 tons of wheat, oats, and barely, and the root crop, 17 tons of potatoes, 25 tons of carrots, 30 tons of beets, 43 tons of turnips, and 2.5 tons of onions. In addition, 15 dairy cows produced milk and butter for the institute and skim milk for the hogs and calves. That year the school sold $667 worth of live hogs.[16]

Not all this food reached the children’s table, however, as produce was also sold on the local market. In 1909, the school added a hothouse “to supply the community with plants of all kinds.”[17] The Women’s Missionary Society noted that their society was rarely called upon for financial contributions because the government per capita grant along with the farm’s produce and sales from other school industries covered all expenses.[18] Boys from the school were sent to work on local farms as occasional labour. They were allowed to spend the wages earned as farm help “in any proper way.”[19]

In later years, this system of “out” students was frowned upon, but when farm labour was very short during World War One, Principal George Raley asked the DIA for special permission to hire out “the older and more robust boys” to local farmers. The DIA suspended the student’s per capita grant while they were away earning wages.[20]

Curriculum

Like most other residential schools, Coqualeetza Residential School followed the half-day system—with children attending classes in the morning or afternoon and dedicating the rest of the school day to industrial training. But the curriculum at Coqualeetza Residential School also deviated from the norm in some interesting ways.

During the school’s first decades, for example, both girls and boys were trained in housekeeping and other domestic work. The reasoning appeared to be that men of “the frontier” should be able to take care of themselves: “We want that our boys shall be generally handy—men of all work—as being the best suited to the conditions of this country. Hence they are taught the care of their own rooms, washing their own clothes, preparing vegetables for meals, and cooking them, scrubbing floors, baking bread, besides all the different parts of the farm and garden work, care of stock, etc.”[21] For many years, boys were the only ones trained in baking.

Such inclusion should not, however, be interpreted as attention to gender equality. In most areas, including recreation, boys and girls were kept quite separate. In addition to farmwork, boys were taught blacksmithing, shoe repair, and rudimentary carpentry. In 1920, with an ever greater proportion of the school’s students coming from northern British Columbia, Principal Raley introduced boat building. “There is not one of the above class who would not be able to find ready employment as soon as he leaves the Institute and returns north,” he wrote.[22] For girls, Raley introduced home nursing to the curriculum. The priority in training girls, however, remained limited to Christian ideas of domesticity, “to give the girls a clear idea of what true womanhood means. This embraces a study of the virtues and graces which go to make happy homes.”[23] On graduation, only the girls were presented with materials to make themselves a complete set of clothes.

Items made by both boys and girls supplied the school’s needs and also the local market. The Women’s Missionary Society reported in 1897, “Four boys make and repair all the shoes, besides doing some custom work for the people outside.” Regarding girls’ work, the society reported, “In the sewing-room all the girls’ clothing is made and most of the boys’, and all clothing repaired…It is intended to extend the dressmaking department by taking orders for work.” [24] Throughout the school’s history, the children’s handiwork was shown at local fairs and exhibitions, often winning cash prizes. On one occasion, the prize money was withheld when fair officials learned that Indigenous children had made the items on display.[25]

On the academic front, the children attended grades 1 to 6, and as early as 1903, a number sat for their high school entrance exams. Principal Hall added a kindergarten class in 1897 and also offered an evening book-keeping course to interested boys and girls.

As at other residential schools, religious instruction was a large component of school life:

The day is begun by prayers in the dormitories on rising; family prayer in the dining-room before breakfast, and in the school-room in the evening, always accompanied by singing and the reading or recitation of Scripture selections. Sabbath School on the Lord’s Day in the forenoon, attendance at the Indian church in the afternoon, and preaching in the Institute in the evening. On Mondays mornings the children meet in classes for special personal religious instruction. On Thursday evenings the regular weekly prayer-meeting is held. We teach the catechism in all the classes at Sabbath School.[26]

According to Principal Raley, the school’s aim was to “make Christian citizens of the pupils” by teaching them to “Fear God” and “Honour the King.”[27] During World War I, patriotism was promoted with nightly presentations—complete with diagrams and maps—on the movements of the British Empire’s armies.[28] Nineteen boys signed up for the war effort. Four were killed overseas and five, wounded.[29]

The children had Saturday afternoon as free time, except when it was withheld as punishment. The boys were allowed out on their own and often went fishing. Girls, however, were chaperoned when they walked in groups in the woods. Occasionally the school held “social evenings” where girls and boys were allowed to mix and play checkers, crokinole, and other board games.[30] There were also camping trips to Cultus Lake—one week for the boys and a different week for the girls. In later years, many children attended the school’s camp during their summer holidays, first at Ocean Park, in Surrey, then at Kitsilano Park, in Vancouver, and finally, at White Rock.

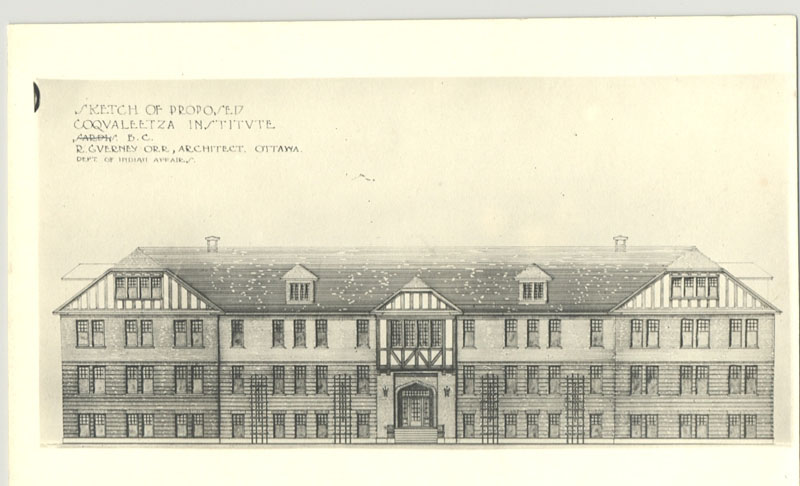

1924: A New Building and a New Curriculum

By 1920, there were 137 children enrolled at Coqualeetza. Although extra tent dorms, and a new hall for lectures and recreation had been added, Principal Raley believed it was time for a completely new building. With government financing, plans were laid, the old building demolished, and in 1924, a new institute, with room for 200 students, opened its doors. Besides housing individual shops for industrial arts (blacksmithing, motor mechanics, small boat building, shoe repair, manual training) and a printing press, Raley hoped the institution’s new layout would provide students with “a bit of the home spirit.” To this end, applying Western concepts of home, he had pressed for sitting rooms and semi-private bedrooms for the older students.[31]

One of the most striking features of the new building, however, was the display of some 800 pieces of Indigenous artwork, all from Raley’s personal collection. The principal sought not only to preserve examples of Indigenous material culture but also to promote their production. As one newspaper reported, “It would be his wish if possible to create an industrial league for the encouragement of the continuation of Indian art and handicraft, creating a market for the better work of this kind, done in the original manner.”[32] In addition to the trades previously taught, Raley introduced classes in wood carving for boys and in basket weaving for girls.

R.C. Scott, who succeeded Raley in 1934, continued and expanded this program. To the girls’ courses, he added carding, spinning, dyeing, knitting and weaving for the production of Cowichan sweaters and hooked rugs “using symbolic native designs.”[33] The boys continued to carve, specializing, with the aid of machinery, in the production of miniature totem poles. Although the DIA did not oppose this work—a DIA grant paid for the girls’ weaving and knitting equipment—some officials questioned aspects of it. “To me the poles that I was shown appear very poor indeed,” wrote one inspector. “They are not much better than the rubbish sent to B.C. from Japan.”[34] The inspector did not disapprove of the boys making poles but objected to them using machinery in their production, a process he believed produced an inauthentic object. He compared Coqualeetza’s work unfavourably with that of the Anglican school on Vancouver Island: “Efforts are being made at Alert Bay Indian Residential School to teach the Indian boys to carve out the totem poles by hand, the Instructor being a well-known carver of such poles.”[35] At Coqualeetza, none of the instructors were First Nations people.

The Board of Home Missions acknowledged that vocational training at Coqualeetza was far from ideal, but pointed out that “of all the residential schools belonging to our own or any other Church, visited by our Commission in May, Coqualeetza was the only one that had a manual training department worthy of the name.”[36] The Board, however, agreed that the school needed to focus on the production of items for daily use rather than of elaborate pieces, such as cabinets and kimonos, for exhibition display—a long tradition at Coqualeetza Residential School.

For his part, Scott defended the curriculum at Coqualeetza but promised to lay more stress on “practical” activities in the boy’s manual training classes. Of the girls’ classes, he wrote, “The girls are taught to plan, prepare and serve a meal similar to one that would be served in the ordinary home. I may say that all our girls use the wash tub. We have no electric washing machines or electric bakeries.”[37]

Scott, who was himself a sea captain, continued the boat-building program started by Raley but increased the size of the boats to those used in the northern areas from which most of his students came. He also added courses in navigation, electricity, radio, and the manufacture, use, and repair of fishing nets. He assured the DIA that these courses would serve the children well after graduation, since “about 75% of the pupils of this School make their living from the sea or from Coast industries.”[38]

Discipline

The different administrators at Coqualeetza Residential School. described discipline at the school as largely good and claimed that they rarely resorted to corporal punishment, preferring instead to suspend privileges when faced with infractions by their students. “No bruises are ever inflicted, and always justice is tempered with mercy; usually the pupil is reasoned with and shown how impossible it is that the offence committed can be allowed to go unpunished,” wrote Principal Hall in 1900.[39] To make it easier to keep order, from early in the school’s history, boys over the age of 16 were not admitted “except in exceptional cases.”[40]

However, both whipping and strapping did occur. Teacher Rachel Large recalled, “The size of those great lads whom I was supposed to chastise with a whip—but never could, intimidated me.”[41] In one case, in 1940, a staff member reported that on little provocation, another staff had swung at a boy (but missed) and then “thrashed” him with a harness trace. The DIA investigated and concluded that although a harness trace had not been used, the strap employed did not meet regulations and the principal’s permission should first have been sought. The Department took no measures against the man or the school, but he was not rehired when most of the staff moved to Alberni Residential School on Coqualeetza’s closing later that year.[42]

Student Health

Coqualeetza, like other residential schools, saw its share of epidemics and faced numerous incidents of tuberculosis among its students. However, unlike some schools, whose administrators wondered aloud whether their schools had contributed to the poor health of the children in their care, at Coqualeetza administrators were convinced that the opposite was true. Again and again, they emphasized “inherited tendencies” of the children and the school’s role in reducing the impact of disease. Principal E. Robson wrote in 1895, “The prevalence of scrofulous ailments—often hereditary—renders the work of the teachers trying, but through their self-denying efforts the health of those instrusted [sic] in their care has been such, when contrasted with the children outside, as to constitute a strong reason for attendance at school, in the minds of parents.”[43] According to historian Mary-Ellen Kelm, by 1905, fifty-five of the Coqualeetza school’s 269 former students had died from TB and other diseases.[44]

When a commission of United Church toured their schools in 1935, they also suggested that the school improved health: “Residential Schools are front-line trenches in the warfare on Indian diseases.”[45] The commission cited Coqualeetza as an example of a school that had not only reduced the incidence of tuberculosis but even cured it. That year the school had begun construction of a “preventorium,” a building separate from the main school where incipient TB cases could take a “rest cure” and, depending on the outcome, be moved to a sanatorium or returned to the school. In 1938, Principal Scott reported that after receiving treatment, six students had been discharged with no signs of the disease.[46] Girls in the home nursing course would help out in the preventorium, although, Scott stressed, “we do not of course allow them to do any nursing where they would come into close contact with tubercular cases.”[47]

School Closing

In 1939, at the request of the Department of Indian Affairs, the Board of Home Missions agreed to turn Coqualeetza Residential School. over to the federal government, which would convert it into a sanatorium to treat Indigenous people who had contracted tuberculosis. In exchange, the government would build a school for 200 students at Alberni (since the one that was there had burned down), improved day schools at Ahousaht and Kitamaat, and day schools at Bella Coola, Cape Mudge and other places.[48] For its part, the Women’s Missionary Society agreed to turn management of Alberni Residential School over to the Board of Home Missions, since Coqualeetza was the only school in British Columbia under the Board’s administration.[49]

The school was closed at the end of June 1940, with most of its students returning to their home communities. Some 50 children, however, were sent to the summer camp at White Rock to await completion of Alberni Residential School.[50] Twenty Anglican students from Coqualeetza Residential School. transferred to St. Michael’s in Alert Bay, overcrowding that school.[51]

Coqualeetza’s equipment and stock were auctioned off in October 1940, and in July 1941, the government bought 46.7 acres of the school lands from the United Church.[52] The Coqualeetza Sanatorium (also called the Coqualeetza Hospital) opened in 1941, was partially destroyed by fire in 1948, and was fully repaired by 1956. The hospital operated until September 1969.

With the hospital’s closure, the Sto:lo organized the Coqualeetza Education Training Centre and occupied the site. At that time, the land was in the hands of the Department of Public Works, with most of it leased to the Department of National Defence.[53] When the army base closed in 1997, the Sto:lo Nation began a formal land claims process to recover the property.[54] Although today part of the site houses the offices of the Sto:lo Nation, as of 2006 negotiations to have it converted to reserve status were still underway.[55]

Footnotes

- Rachel E. Large, “Coqualeetza Industrial Institute,” [c. 1960], Add Mss 1, box 6, file 219, Chilliwack Archives. ↩

- Thomas Crosby, Among the An-ko-menums; or, Flathead Tribes of Indians of the Pacific Coast (Toronto: W. Briggs, 1907), 169–171. ↩

- C.M. Tate, Our Indian Missions in British Columbia (Toronto: Methodist Young People’s Forward Movement for Missions, 1800), 15–16. ↩

- H.L. Platt, “Coqualeetza Institute,” The Story of the Years: A History of the Women’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, Canada, from 1881 to 1906 ([Toronto: Women’s Missionary Society, Methodist Church], 1908), vol. 1, p. 56. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Mary Ellen Kelm, “Knott, Caroline Sarah (Tate),” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. ↩

- Platt, “Coqualeetza Institute,” 56–57. ↩

- Coqualeetza Cultural Education Centre, “Capital Project”; Brent D. Galloway, Dictionary of Upriver Holkemelem (Berkley: University of California Press, 2009), 185; Jonathon Clapperton, “Building Longhouses and Constructing Identities: A Brief History of the Coqualeetza Longhouse and Shxwt’a:selhawtxw,” University of the Fraser Valley Research Review 2, no. 2: 101. ↩

- Platt, “Coqualeetza Institute,” 57; [newspaper clipping, c. 1891], Coqualeetza IRS file, Chilliwack Archives. ↩

- “The Industrial Institute,” Chilliwack Progress, May 2, 1894, RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt.1, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). ↩

- Platt, “Coqualeetza Institute,” 58. ↩

- T. Ferrier, “Report of the Coqualeetza Institute for the Year Ending June 30, 1907,” RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ferrier, “Report of the Coqualeetza Institute for the Year Ending June 30, 1910,” RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- J. Hall, principal, to Secretary General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), Aug. 25, 1899, Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual reports, 1899, pp. 392–395. ↩

- Hall to A.W. Vowell, Indian Superintendent, Dec. 1, 1897, RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Hall to SGIA, July 1, 1903, DIA annual reports, 1903, pp. 426–429. ↩

- R.H. Cairns, principal, to Frank Pedely, Desputy SGIA, Mar. 31, 1909, DIA annual reports, 1909, pp. 416–418. ↩

- E.S. Strachan and W.E. Ross, “Coqualeetza Institute, Chilliwack, B.C.” in The Story of the Years: A History of the Women’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, Canada, 1906–1916 (Toronto: Women’s Missionary Society, Methodist Church, 1917), vol. 3, p. 31. ↩

- Hall to SGIA, Aug. 25, 1899. ↩

- George Raley, principal, to J.D. McLean, secretary, DIA, Jan. 15, 1918, and McLean to Raley, Jan. 25, 1918, RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Hall to SGIA, Aug. 23, 1900, DIA annual reports, 1900, pp. 424-427. ↩

- “Coqualeetza Commencement Exercises 1920,” RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- “Vestiga Nulla Retrorsum,” pamphlet, Oct. 21, 1924, Add Mss 1175, vol. 4, file 12, Denys Nelson Papers, British Columbia Archives (BCA). ↩

- Platt, “Coqualeetza Institute,” 60. ↩

- Hall to SGIA, Aug. 19, 1898, DIA annual reports, 1898, pp. 341–344. ↩

- Platt, “Coqualeetza Institute,” 63. ↩

- “Vestiga Nulla Retrorsum,” Oct. 21, 1924.↩

- Strachan and Ross, “Coqualeetza Institute, Chilliwack, B.C.,” 32–33. ↩

- “Vestiga Nulla Retrorsum,” Oct. 21, 1924.↩

- Hall to SGIA, Aug. 25, 1899. ↩

- Paige Raibmon, “‘A New Understanding of Things Indian’: George Raley’s Negotiation of Residential School Experience,” B.C. Studies, no. 110 (Summer 1996): 72. ↩

- [newspaper clipping, 1924], Coqualeetza Residential School file, Chilliwack Archives. ↩

- “Extract from Inspector Barry’s Report on his visit to the Coqualeetza Residential School on October 28, 29 and 30, 1935,” RG10, vol. 6442, file 880-11, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Kenneth J. Beaton, Board of home Missions, to J.D. Sutherland, DIA, Dec. 21, 1935, RG10, vol. 6442, file 880-11, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Scott to R.A. Hoey, Superintendent of Welfare and Training, Indian Affairs Branch, May 14, 1938, RG10, vol. 6443, file 880-11, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Hall to Frank Devlin, Indian Agent, Jan. 19, 1900, RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- E. Robson, principal, to SGIA, DIA annual reports, 1895, Aug. 10, 1895, pp. 154–155. ↩

- Large, “Coqualeetza Industrial Institute.”↩

- Barry to D.M. MacKay, Indian Commissioner, June 24, 1940, RG10, vol. 6442, file 869-1, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- Robson, to SGIA, Aug. 10, 1895. ↩

- Mary Ellen Kelm, “A Scandalous Procession: Residential Schooling and the Reformation of Aboriginal Bodies, 1900–1950.” In Children, Teachers, and Schools: In the History of British Columbia, edited by Jean Barman, Neil Sutherland, and J.D. Wilson (Calgary: Detselig Enterprises, 2003), 90-91. ↩

- Board of Home Missions and Women’s Missionary Society of the United Church of Canada (UCC), “Report of Commission Appointed to Survey Indian Education,” 1935, UCCA. ↩

- Scott to Parents, Graduates and Friends, Jan. 14, 1938, newsletter, RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- Scott to Hoey, May 14, 1938. ↩

- “Minute of the Sub-Executive of W.M.S. Committee July 28, 1939,” UCCA. ↩

- “Resolution Adopted by the Executive of the Board of Home Mission of the United Church of Canada, at its Meeting, June 12, 1939,” RG10, vol. 6422, file 869-1, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- Hoey to Scott, Aug. 12, 1940, RG10, vol. 6431, vile 877-1, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- T.B.R. Westgate, Secretary, Indian and Eskimo Residential Schools Commission, Missionary Society of the Church of England, to H.W. McGill, director, Indian Affairs Branch, RG10, vol. 6426, file 875-1, pt. 4, LAC. ↩

- P.C. 28/4840, July 3, 1941, vol. 1, file 987/25-1-016, CR-HQ. ↩

- “Indian Frsutrated by Neogitations for Coqualeetza Complex,” Chilliwack Progress, Jan. 14, 1976, and “Unresolved Questions Cloud Coqualeetza History,” Chilliwack Progress, Apr. 7, 1976, both in Add Mss 1, box 6, file 220, Chilliwack Archives. ↩

- “Stolo Land Claim Alive in B.C. Court,” Chilliwack Progress, Aug. 5, 2011. ↩

- “Stó:lô Nation Society FY 2005–2006 Performance Report”; Valerie Sam, Sto:lo Nation Land Department, to Board Members, Fraser Valley Regional District, May 26, 2005. ↩