Brandon Residential School

Dates of Operation

1895-1972

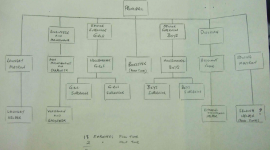

Operated by the Missionary Society of the Methodist Church and, after 1925, by the Board of Home Missions of the United Church of Canada. In 1969, the federal government assumed management of the school (now a residence only) and turned it over to the Oblates of Mary Immaculate until the school’s closure in 1972.

Location

In the municipality of Cornwallis, in southern Manitoba, five kilometres northwest of Brandon on the north bank of the Assiniboine River.

I am informed that it is the intention of the Methodist Mission Society to erect an Industrial School somewhere about Brandon, when first the matter of the institution was mentioned to our people we were in the hopes to see not only one but two or three such buildings erected in Berens River Agency where they would be a benefit not only to our children but to all of us, old and young, as our people seeing the young ones taught the art of agriculture, carpentry etc. could observe and learn also.

—Chief Jacob Berens (Nah-wee-kee-sick-qauh-yash) defending his proposal for on-reserve schools at locations central to the Treaty 5 communities, in keeping with the terms of the treaty.[1]

Establishment

In 1888, the Methodist Missionary Society pressed the federal government for an industrial institute for the Indigenous communities of the Lake Winnipeg region.[2] The Methodists were extending their educational work into the Canadian northwest, and, like other Christian denominations and the federal government itself, believed that large industrial schools placed far from home communities and family influence were the best way to ensure the assimilation of children. “Knowing the serious disadvantage of having such an institution in or near an Indian Reserve, we asked that this one might be located in southern Manitoba,” wrote Dr. A. Sutherland, general secretary of the missionary society.[3]

The Methodists hope to draw students from the Cree and Saulteaux communities where they had missions—Berens River, Fisher River, Norway House, Oxford House, Cross Lake, and Nelson House. In 1875, some of these communities had negotiated Treaty 5, and others would adhere to it in the years to come. In the written treaty, the Crown had promised, among other things, “to maintain schools for instruction in such reserves…whenever the Indians of the reserve shall desire it.”[4] In response to the Missionary Society’s request, the Department of Indian Affairs, after determining that 1,300 members of Treaty 5 communities were affiliated with the Methodists, agreed to finance construction of an industrial school under Methodist management and to provide ongoing funding.[5]

However, finding a suitable location proved difficult. Both the federal government and the Methodists wanted a place with ample farmland, proximity to settler society, and a railroad close by. For a time, Selkirk was considered, but the Methodists did not want their school in the same vicinity as the Anglicans’ school.[6] Even though the First Nations of Treaty 5 had called for schools to be located within their home communities, by 1891, the church and government settled on Brandon, where the city offered lands next to its Experimental Farm in exchange for Crown lands elsewhere.

After acquiring the school site—320 acres on the Assiniboine River—the government began construction of the main school building, a three-storey structure with accommodation for 125 students. Brandon Industrial Institute opened in July 1895 with 38 children enrolled and the Rev. J. Semmens, “a master of the Cree language,” as its first principal.[7]

Recruitment

First Nations communities were not consulted about the school’s location. When they learned that Brandon had been selected, Chief Jacob Berens, of Berens River and a Methodist himself, and other leaders petitioned the government:

We heard we were likely to get Indian industrial schools in this Agency, and we were glad and would have been willing to send our children to the Institution. But now we are informed that…only one is to be established and that at Brandon, we cannot really think of ever sending any of our children so far away from out reserves even for the purpose of getting an education.[8]

Chief Berens also wrote to the Missionary Society, calling for a school “in our midst” and appealing to the Methodists’ sentiments: “Our hearts are sad for we cannot think of sending our children away, such a long distance from their people and their homes…we love our children like the white man and are pleased to have them near us.”[9] Sutherland responded, but only to confirm the decision already taken and to dismiss Berens’ arguments as the product of outside influences antagonistic to the Methodists.[10] Berens wrote again, reminding Sutherland that “an Industrial school without pupils will neither benefit your society nor benefit our people.”[11]

In the months before the school was to open, Principal Semmens twice visited the different communities around and north of Lake Winnipeg in search of students. On his first trip, Semmens recorded some of the questions put to him by parents:

- Will the children return to us after their course at School?

- Is it the object of the Gov’t to destroy our language and our tribal life?

- Is it the purpose to enslave our children and make money out of them?

- Can the children return at their own wish or at the wish of the parents before the term at School expires?

- …Will the Government keep this promise or break it as they have others made in like beautiful language? [12]

Semmens also noted the opposition of many community members to the school because of its great distance from Lake Winnipeg. From the seven communities visited, he was able to sign up only 35 children, who returned with him on his second trip to become Brandon Residential School’s first students. When Semmens expressed his concern about the resistance he had encountered, the Department of Indian Affairs promised to enforce, if necessary, federal regulations stipulating the “compulsory education of Indian children.”[13]

According to government criteria, students at the school were to be from communities under treaty, preferably orphans, and of Indian parentage on both sides. The government also recommended recruiting children from communities closer to the school, believing that they would receive more benefit from education than children from northern communities who remained dependent on hunting and fishing.[14]The Methodists, however, were committed to bringing in students from the distant places where the bulk of their missions were located. Despite the established criteria, the school soon received permission to accept non-treaty children in order to fill it.

Once Brandon Residential School was open, Semmens found that community opposition began to wane. At the end of the 1895/96 school year, he reported, “This change of front has, I believe, resulted mainly from the letters which the children themselves have written home, letters which in the main have been devoted to expressions of satisfaction with their surroundings and of desire that others might be sent in to share their advantage.”[15] However, when communities heard rumours that schools were to be built on the reserves, they again held their children back, and the school had to rely on northern communities “beyond the treaty limits” and on the overflow of the Anglican school at Elkhorn.[16] By 1899, enrollment was close to 100.

With the opening of Norway House Residential School in 1900, the school at Brandon was once again pressed for students. This time administrators looked to Ontario, where they thought they would find children more able to put to use the agricultural training provided at Brandon and less likely to run away.[17] The Department of Indian Affairs denied the request at first, citing the complexities of using funding earmarked for one part of the country to educate children from another. However, in 1923, when the new residential school at Edmonton enrolled many of the children who had transferred to Brandon after Red Deer Residential School closed in 1919, the department acquiesced, granting the admission of “orphans and destitute children” from the neighbouring province.[18] Many children continued to come from Winnipeg Lake district, with an increasing number from the Nelson River Valley. Starting in the 1930s, Brandon Residential School also drew older children from the residential school at Round Lake, Saskatchewan. Children who found themselves in the court system were sent to the school as well.[19]

Curriculum

Classroom hours at Brandon Residential School were from 9 a.m. to noon and from 1:30 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. Children, except for the smallest, generally attended school during one of these periods and spent the remainder of their day working on the farm or in the school.[20] Classroom subjects included reading, writing, arithmetic, spelling, drilling and calisthenics. Soon after the school’s opening, these were expanded to include drawing, geography, English composition, Canadian history, and music.

Religious training was also integrated into the curriculum. Prayers were recited after breakfast, before school, in the evening, and before bed. Staff and children sang hymns “interspersed with the duties of the day” and attended as many as three church services—one of them in the city of Brandon—on Sundays.[21]

A large portion of the children’s days was spent in vocational training and chores. For the boys, this meant working on the farm, building fences, taking care of the animals, mending clothes, and baking bread. By 1900 they also learned some tinsmithing. Overall, however, instruction in skilled trades was not emphasized. In 1902, Principal Thompson Ferrier wrote that while boys received some training in “the use of hammer and saw,” training in farm work was “more natural and will be more successful than forcing [the graduates] into the overcrowded trades and professions of to-day.”[22]

The girls’ days were filled with dairy work, sewing, cooking, dining-room work, and general housekeeping.[23] They were sometimes sent out to work as domestic servants for local white settlers—including the principal’s family in Brandon, where they took turns working for a month at a time. Authorities often saw placements of this kind as an indicator of the school’s success. Nonetheless, Rev. Semmens observed that girls in domestic service would “long for speedy return to the social advantages of the school.”[24] By 1901 some of the girls began to receive training in nursing under a professional nurse.

Farming

Much of the land at Brandon was a working farm, with 200 acres under cultivation before the industrial institute was established there. The soil was very good, an advantage the farms of many Indian residential schools did not have, so that even in the school’s first year it produced 630 bushels of wheat and 772 bushels of oats, as well as 508 bushels of root vegetables and eight tons of hay.[25] Proceeds from the sale of such produce supplemented the per capita grant the Missionary Society received to run the school to the extent that by 1906, Brandon’s books showed a small profit.[26]

In 1911, the federal government purchased additional land—640 acres—for the school’s use. That year the grain harvest consisted of 1,017 bushels of wheat, 2,019 bushels of oats, 595 bushels of barley, 80 tons of corn fodder, and 650 dozen ears of table corn.[27] As machinery was required to work such large holdings, boys were taught to repair and operate farm equipment and gasoline engines.[28] By 1930, a number of the older boys were attending the Tractor School put on by the International Harvester Company.

School administrators, however, thought that the school’s vegetable garden provided the most useful training for their students. They judged that Aboriginal boys would never become extensive grain growers but could grow roots “with a minimum of labour and a maximum of profit.”[29] Principal Ferrier introduced a fruit orchard for the same purpose: “This garden teaches in a practical way that the fruits for which they roam the country can be had in better quality and with less labour at their doors.”[30]

Boys at the school were sometimes hired out to help on neighbouring farms and, on graduation, often found permanent work in the area. Since farming on their own reserves was not profitable given the soil, climate, and government policies that limited First Nations farmers to small-scale production, graduates were encouraged to take up homesteads on the Methodists’ File Hills Colony in Saskatchewan, which a number did.[31]

In the 1950s, Brandon Residential School followed the nationwide trend away from agricultural and other on-site vocational training at Indian residential schools. In 1957, the school’s farmland was leased to the neighbouring Experimental Farm, and all the cattle were sold.[32] In 1961, the land was sold to the Department of Agriculture.

1930: A New School is Built

The 1920s were a time of economic prosperity and the promotion of things “modern.” Not surprisingly, these trends had their impact on Indian residential schools. As one article described it, “Through the aid of increased appropriations by Parliament during that time, the Department of Indian Affairs had been able to enlarge existing buildings, and construct more modern and fireproof schools, whilst higher salaries and grants have attracted better qualified teachers and instructors.”[33] Brandon was one of a number of schools to see major changes as a result.

In 1927, the general secretary of the United Church of Canada called for a new school building, arguing that the existing building was so outdated that it was difficult to carry on the work: “The location of the school is strategically situated for visitors. Every year they come from all parts of Canada, as well as from other lands. The usual comment is that our main building is not in keeping with the beautiful farm, lawns, and outbuildings.”[34] Brandon Residential School had always been something of a flagship for the Methodist (now United Church) residential schools. In 1918, the governor general of Canada had visited the institution, and in 1920 it was one of the locations chosen for an educational film commissioned by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The school was demolished in the summer of 1929, and in September the cornerstone of a new building was laid. Its official opening, however, did not take place until July 1930. In the meantime, Brandon’s students were sent home to their reserves or, in the case of 83 orphans, to Edmonton Residential School.[35] A public relations drive accompanied the opening. The school sent out a pamphlet promoting the new institution and promising prospective students the necessary training “to become happy, successful, and useful citizens when they go out to take their place in life.”[36] Brandon Residential School was particularly interested in expanding its roster of high school students, for whom a separate classroom in the new building had been provided.

High School Students

Even before the new school opened, a number of students from Brandon Residential School had taken their high school entrance exams in order to attend high school in the city of Brandon. In 1927, six students started classes at Brandon Collegiate while still living in the residential school. The next year, there were ten. In response to this demand, The new, modern institute as it looked c. 1940. During this period, an increasing number of children at Brandon Residential School bussed into the city to attend high school. UCCA, 1986.158P/24. started teaching high school courses, and when the new school building opened in 1930, kindergarten through grade 10 was offered. Still, a number of older students travelled daily to Brandon to attend the Collegiate, the Normal School, or the Business School. By 1931, there were 25 high school students as well as seven boys attending Brandon Technical School, which specialized in automobile mechanics and gas welding.

Student Health and Welfare

From 1898 to 1906 more than 25 children died at Brandon Residential School, and others were sent home from the school when they were seriously ill.[37] In addition to these deaths, in 1903, six children, an adult First Nations man, and Rev. MacLachlan of the Berens River Mission drowned in Lake Manitoba while transporting the children from Norway House to Brandon Residential School in an open sail boat.[38] As at other Indian residential schools, the main cause of the children’s deaths in this early period was tuberculosis, frequently aggravated by other illnesses that swept the school from time to time. Over the course of the school’s history, there were two cemeteries associated with Brandon Residential School.

Administrators did not attribute these deaths to the conditions at the institute, since they almost always reported a healthy school environment and population. In 1918, however, one inspector painted a more negative picture of health conditions:

In the room called the hospital at the time of my visit, there were two pupils, one girl dying of consumption. The Nurse said she might die any moment, and the other girl has a concussion from a fall in the winter. There are three boys sick in the dormitories, one of them has been in the Brandon Hospital but is now recovering. He has still an open wound in his leg from which comes pus. Another boy is in bed with what he thinks is an itch, and I told the Nurse to send for the doctor and have him examined. The third boy sick has ptomaine poisoning. The Nurse reports (though she refuses to put it in writing), that since February 1917, there were three deaths from tuberculosis. There were five cases of pneumonia, all recovered, 36 cases of measles and accommodation for three only, all recovered. There were 15 cases of grippe, patients averaging from 5 to 12 days each. All of these students had to be kept in the dormitories.[39].

Inspector Jackson stated also that the school was overcrowded, with some boys sleeping two to a bed, that the hospital room was in poor shape, and that improvements had not been made despite his recommendations. He urged authorities to have the children examined by a doctor before they were admitted.

When the new school building opened in 1930, health and hygiene were major concerns. In its promotional materials, the school stressed that a doctor was called whenever one was needed, that students were also screened and visited by the staff of a local clinic, and that they were well fed: “A wholesome and balanced diet is being followed. The pupils are weighed regularly and satisfactory gains in weight are recorded. A number of boys gained twenty to thirty pounds each during the first three months of the school year, and taken altogether the Ninette Clinic found the pupils average five per cent overweight for boys and girls of their age and height.”[40]

Despite these claims, in 1935, the mother of one boy wrote the Department of Indian Affairs alarmed that the children weren’t getting enough to eat. She accused Principal Doyle of “training the children to be thieves” because out of hunger they would shoplift for food at the A.T. Eaton’s store in Brandon. “These things never happen before, about children going out to steal food to fill their empty bodys,” she wrote. [41] Citing the poor and very weak condition of returning children, she asked to have her two sons home for the summer. The principal and the department denied her request, claiming that she only wished to have them home to work on her homestead.[42]

E.T. Chapin, who became principal in 1940 on Doyle’s retirement, found the school more than he could handle. In 1942 alone, at least 12 children, ages 10 to 15, ran away.[43] According to the Superintendent of Missions of the United Church, the constraints posed by WWII—reducing the availability of both staff and supplies—were largely to blame: “I think that, if the war had not come along with all its upheavals, everything would have turned out well.”[44] During this period, many parents sent petitions about the poor food and clothing their children were receiving and, in one case, a Brandon resident alerted the RCMP of rumours of abusive and indecent treatment of the children.[45]

Following the war, however, conditions at the school—now under Principal Oliver B. Strapp—continued to deteriorate. In 1951, the department made a formal investigation to find out why so many students, especially boys, were running away. The children reported that they did not have much time to play, they had too much work in the kitchen and the farm, they didn’t have proper clothes to wear, they did not get enough to eat, and they were no longer allowed to play baseball and hockey.[46]

Reorganization and Integration

A new principal, Roy Ingis, was appointed in 1956, but the problems at Brandon Residential School continued. Inglis’s health suffered, as did his predecessors, and soon he, too, had to resign. One problem was managing relations among children of vastly different ages, which ranged from 7 to 20. Harry Atkinson, who was brought in to give Inglis some relief, reported bullying on the part of the older children and impudence and fear from the younger.[47] Atkinson added that staff efforts to maintain order had left the children with very little they were allowed to do:

The W.M.S. worker told me she had got the girls interested in knitting, but the little girls took a ball of wool and played with it it went down the toilet. Knitting was stopped. I found a big box of play guns, collected because it was not though[t] wise to let them play cowboys. all ropes were collected because in the dim past a boy had made a ladder to get out of the [dorm]. no skipping ropes. But the small boys were holding me up with paper guns made out of magazines and shoelaces. I took the boys into the hall and taught them games the girls demanded some. I tried to get them to plan a program for Easter week but they were afraid to open their mouths.[48]

In 1957, the Department of Indian Affairs recommended a major reorganization, and the United Church agreed. The proposal, which was carried out under the new principal, Lachlan Maclean, was to divide the student populations of both Brandon and Portage la Prairie residential schools into younger, elementary students, and older, junior high students. Brandon Residential Schoolwould teach grades 1 to 6 to a population of some 180 children from ages 6 to 11. As part of the reorganization, the farm was sold off, the school building was renovated and a completely new staff was hired. In 1960, the position of matron was eliminated. To make these changes, the school closed during the summer of 1957.

Three years later, the Department of Indian Affairs launched its integration program aimed at bringing First Nations students into the public school system. The Department replaced teachers with part-time teacher-advisers at select residential schools, including Brandon, which would soon serve solely as a hostel for children attending nearby non-Indigenous schools.[49] Twenty-six boarders at Brandon Residential School had started bussing to local public schools in 1958. By 1960, they numbered 85 out of a total 200 children in residence. As part of the integration effort, some 75 children also attended Sunday school at the three United Churches in Brandon.

In a parallel initiative aimed at promoting the assimilation of First Nations students to Canadian society, in 1961 the school started to board children in non-Indigenous homes in the city. A local news article on the integration claimed, “It was found that those who spent their Christmas holiday in foster homes had no difficulty in slipping back into the school, dormitory and dining room routine, while those who returned from their homes on the reserve resented the necessary discipline after their brief lapse into tribal life.”[50] Administrators also believed foster homes would teach the children about nuclear family life. “In this way the children are learning how families live together in consideration and love, one for the other and how a family, through its loyalty endeavours to work as one complete unit,” Principal Ford Bond wrote in a school newsletter.[51] By 1965, some 50 children ages 8 to 14 were boarding in private homes and another 175 remained in residence.

School Closing

In 1969, the Department of Indian Affairs took over all the Indian student residences with the intention of managing them or, in some cases, turning them over to First Nations organizations. The Brandon residence, however, was soon returned to church hands—this time those of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a Roman Catholic missionary congregation. The United Church was consulted and gave its approval. The Oblates ran the residence for two years, until it closed in 1972.

The school building was abandoned and was demolished in 2006.[52]

Footnotes

- Chief Jacob Berens, Berens River, to A. Sutherland, Secretary General of Missionary Society, Aug. 12, 1891, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Extract from copy of Report of the Sub Committee of the General Board of Missions of the Methodist Church adopted by the Board September 14th/88,” 1888., RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- A. Sutherland, General Secretary, Mission Board, to SGIA, Jan. 18, 1890, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Treaty 5 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteaux and Swampy Cree Tribes of Indians at Beren”s River and Norway House with Adhesions.” (PDF) ↩

- Reed to SGIA, Jan. 15, 1889; R. Sinclair, memorandum, Dec. 12, 1890, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Sutherland to SGIA, Dec. 18, 1890, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Department of Indian Affairs annual reports, 1895, p. 203; “Corner Stone of New Indian School,” Brandon Sun, Sept. 26, 1929, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Jacob Berens, chief, et al, to E. McColl, Inspector of Indian Agencies, Feb. 25, 1892, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. See also Magnus Beardy?., headman, Norway House, et al to Angus Mackay, Indian Agent, Apr. 9, 1892, and Jacob Ross, chief, Cross Lake, et al, statement, Jan. 21, 1895, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Berens to Sutherland, Aug. 12, 1891. ↩

- Sutherland to Berens, Sept. 23, 1891, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, part 1, LAC. ↩

- Berens to Sutherland, Jan. 8, 1892, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, part 1, LAC. ↩

- J. Semmens to McColl, Feb. 19, 1895, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, part 1, LAC. ↩

- Deputy SGIA to McColl, Mar. 8, 1895, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, part 1, LAC. ↩

- Deputy SGIA to McColl, Apr. 23, 1895, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, part 1, LAC. ↩

- Semmens to SGIA, July 20, 1896, DIA annual reports, 1896, pp. 312–316. ↩

- Semmens to SGIA, July 1, 1898, DIA annual reports, 1898, pp. 266–269; Ferrier to Duncan C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, Nov. 28, 1923, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 2, LAC. In 1900, Ferrier was accused of paying northern Manitoba families to send their children to Brandon. DIA official Martin Benson considered the charge unfounded, but he wrote, erring to the protocols Aboriginal parents insisted on when making such agreements and commitments, “He may, however, make some present by way of clothing or otherwise to induce them to part with their children as it is said to be pretty generally the practice in the West to fill up the schools by this means.” See Benson to Deputy SGIA, Mar. 30, 1900, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Martin Benson, Educational Branch, to Deputy SGIA, Sept. 16, 1906. ↩

- Scott to Ferrier, Dec. 12, 1923, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 2, LAC. Scott suggested scouting for children in Sarnia and Mud Lake. ↩

- C.E. Manning to Duncan C. Scott, December 16, 1927, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt 2, LAC. ↩

- Semmens to SGIA, July 20, 1896, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- T. Ferrier, principal, to SGIA, July 1, 1902, DIA annual reports, 1902, pp. 310–312. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Semmens to SGIA, June 30, 1897, DIA annuals reports, 1897, pp. 232–236. ↩

- Semmens to SGIA, July 20, 1896. ↩

- “Brandon Industrial School (Methodists),” DIA annual reports, 1906, p. 154. ↩

- “The Report of Rev. T. Ferrier, Principal of the Brandon Industrial School, Brandon, Man., for the Year Ended March 31, 1912,” DIA annual reports, 1912, pp. 523–425. ↩

- “Brandon Industrial School (Methodist),” DIA annual reports, 1916, pt. 2, pp. 211–212. ↩

- Semmens to SGIA, July 20, 1896. ↩

- Ferrier to Frank Pedley, Deputy SGIA, July 1, 1905, DIA annual reports, 1905, pp. 295–297. ↩

- Martin Benson, DIA, to Deputy SGIA, Mar. 30, 1900, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 1, LAC. On farming policies, see Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990). ↩

- R.D. Ragan, Regional Supervisor of Indian Agencies, to R.F. Davey, Superintendent of Education, Indian Affairs Branch, Feb. 8, 1957, 509/2/2-5, box J, file 4, United Church of Canada Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- “Improve Facilities for Indian Education,” Natural Resources Canada, Oct. 1930, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- C.E. Manning, Board of Home Missions, to Scott, Dec. 16, 1927, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- J.D. McLean, Acting Deputy SGIA to Charles Stewart, and “Corner Stone of New Indian School Laid,” Brandon Sun, Sept. 26, 1929, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-5, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Doyle, “To Indian Agents, Missionaries, Teachers, and Parents or Guardians of Indian Children,” Mar. 16, 1931, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-5, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- See DIA annual reports, 1899 to 1906. ↩

- DIA annual report, 1903, p. 238. ↩

- “Extract from report of Inspector Jackson on the Brandon Industrial School dated May 4, 1918,” RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Doyle, “To Indian Agents, Missionaries, Teachers, and Parents or Guardians of Indian Children,” Mar. 21, 1932, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-5, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Mrs. Geo Perger to Honorable Sir, November 18, 1935, RG10, vol. 6258, file 576-10, pt. 9, LAC (reel C-8650). The inspector argued that the children stole toys and candy and not out of hunger. ↩

- A.G. Hamilton, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to Mr. Sutherland, January 14, 1936, RG10, vol. 6258, file 576-10, pt. 9, LAC. ↩

- R.C.M.P., The Role of the RCMP during the Indian Residential School System, p. 346. ↩

- J.A. Cormie., Superintendent of Missions, to E.T. Chapin, Principal, Apr. 28, 1944, 509/2/2-5, file 2, Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- See, for example, J.A. Regan, Criminal Investigation, to Director, Indian Affairs, November 15, 1944, RG10, vol. 6255, file 576-1, pt. 4, LAC. ↩

- G.H. Marcoux to R.S. Davie, Regional Supervisor, Indian Affairs Branch, Oct. 12, 1951, RG10. vol. 7194, file 511/25-1-015, LAC. ↩

- Harry Atkinson to George MacMillian, Apr. 17, 1957, 509/2/2-5, box J, file 4, Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- DIA annual reports, 1960, p. 56. ↩

- “A Way to Integration,” Brandon Sun, Jan. 17, 1961, 509/2/2-5, box J, file 5, Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Ford Bond, principal, “Indian Residential School,” newsletter, Nov. 16, 1960, , 509/2/2-5, box J, file 5, Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives.↩

- Elsie Catcheway, “Destroying the Evidence of Our Past,” Grassroots News, Apr. 18, 2006. ↩