Edmonton Residential School

Dates of Operation

1924–1966

Operated by the Missionary Society of the Methodist Church and, after 1925, by the United Church of Canada.

Locations

Near the town of St. Albert, approximately 10 miles northwest of downtown Edmonton, Alberta.

Dear Mom and Dad,

Just thought I’d drop you a few lines to let you know that I’m all right and hoping you are the same. I just want to thank all of you for sending those wonderful presents…

Well Mom and dad the main reason for my writing is that I want to go home. I’m not homesick or anything, just…this morning at 2 a.m. [he] woke us up and started to preach to us on how stupid the Indian was…Then this morning at 5 a.m. [he] got us up to go and scrub the basement. It was there I decided I’d like to go home because [he] slapped me around for not getting a haircut that morning…so don’t be surprised if you see me home pretty soon. I was planning to try to stick out the whole term, but [he] threw a monkey-wrench into my plans.

P.S. the Christmas I spent here was the worst one in my whole life.

—letter from Edmonton Residential School student to his parents, Jan. 8, 1962.[1]

Establishment

Edmonton Residential School replaced the Red Deer Residential School, which had closed in 1919, as the Methodist’s school for Cree children from northern Alberta, primarily the Treaty 6 communities of the Hobbema, Edmonton, and Saddle Lake Indian Agencies. It was built at a time when the federal government was replacing many of the older church-built residential schools with larger “modern” institutes.

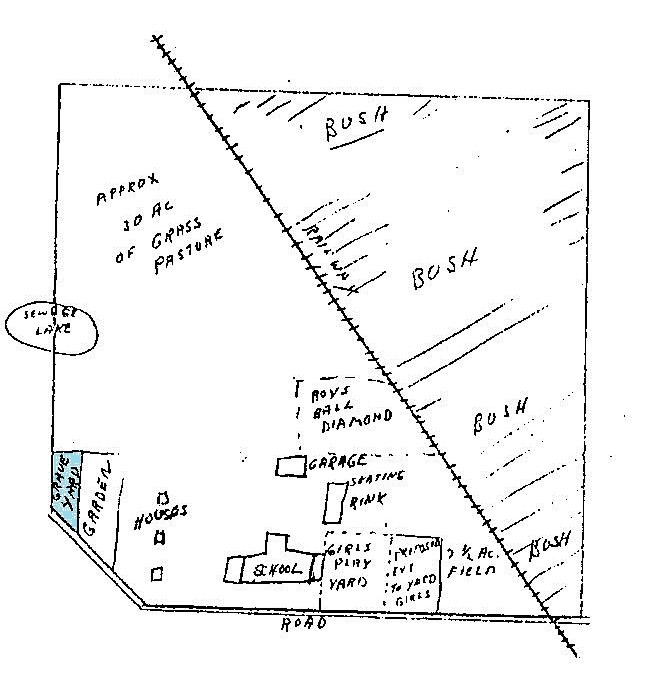

Church officials chose St. Albert, just outside of Edmonton, as the location for the new school because it was closer than Red Deer to the First Nations communities of Alberta’s north. The Department of Indian Affairs agreed to the move and in January 1920 bought an 855-acre farm to serve as the school site. The Missionary Society began farming immediately with the hope that revenue from the farm would help finance construction of the school’s building. It turned out, however, that the first three years produced a loss, and the Church had to turn to the DIA for further support.[2] In 1922, by parliamentary vote, the DIA agreed to finance construction of the main school building and provide a per capita grant.[3] Edmonton Residential School began accepting students in March 1924 and opened officially in October of the same year.[4]

The new residence provided accommodation for 125 children and 12 staff. Although not many of its first students had attended Red Deer before coming to Edmonton—Red Deer students having graduated or transferred to other schools in the meantime—many of their parents had been enrolled at Red Deer. J.F. Woodsworth, the principal at Red Deer when it closed, assumed the same post at Edmonton, remaining there until 1946.

Curriculum and Farming

Like Red Deer before it, Edmonton Residential School covered grades 1 to 8 and operated on the half-day system, with classes in the morning and vocational training (farming) in the afternoon. During the harvest, older boys often spent the entire day on the farm, which, by 1929, consisted of 500 acres under cultivation, including 110 acres of wheat, 125 acres of oats, and 40 acres of barley. The potato crop that year produced 3,000 bushels. By 1933, livestock consisted of 15 horses, 59 cattle (both beef and dairy), 135 pigs, 50 chickens and 25 turkeys.[5]

Over the life of the school, the farm contributed to the institution’s finances. The children’s labour produced most of the food consumed at the school; wheat was milled on site and cattle and pigs, slaughtered. The hogs were sold on the market, and when there were not enough older boys in the school to farm all 500 acres, Woodsworth leased several hundred acres to neighbours to sharecrop.[6] “Mr. Woodworth has made a real business of raising hogs. He sells quite a number each year and they are sold as ‘selects,’” wrote one inspector. The grains harvested, however, were found to be of little value and used mostly to feed the animals.[7]

The emphasis on farm work at the expense of academic study was a constant source of friction between the school, on the one hand, and the children, their parents and visiting inspectors, on the other. In 1930, one boy who pleaded to be returned home or transferred to another school wrote, “I just went to school three days since I came here, that isn’t why my father send me here to work, he send me here to go to school and study hard, and to learn to read and write.”[8] The boy stated that he had to have someone write the letter for him because he had not yet learned “anything at all.” Indian Agent Mortimer, to whom the boy was writing, confirmed that he found it difficult to convince parents in his agency (in British Columbia) to send their children to Edmonton because of complaints that the students were “continually working on the farm, thereby getting little or no education.”[9]

Principal Woodsworth defended the intensive farm labour demanded of the students, arguing that “farm education” was “the best kind of training they could have.” In his writings, Woodsworth often extolled the Christian virtues of farming life, a conviction that reflected the church’s position that Indigenous fishers, hunters, and trappers should transform into Christian farmers. He criticized parents who wanted their children “suddenly to become fine scholars, after allowing them to run the streets of their villages until they are big boys and girls” and praised the school’s regime for the “discipline and restraint” it instilled in them.[10]

The DIA also favoured the focus on agriculture. In 1929, when the Indian commissioner reported that girls at Edmonton Residential School were not doing the milking, the DIA ordered the school to begin instruction immediately. “What are we going to do when these women return to their reserves as farmers and are not able to milk cows? Are they to employ maids?” wrote the commissioner. He added, “One of our greatest difficulties is to get these people to keep milk cows,” and he lamented that men on the reserves would not do the milking.[11]

Farming and ranching, for boys, and housework, for girls, was the only kind of vocational training offered at the school until Principal Staley replaced Woodsworth in 1946 on the latter’s retirement. Staley promised “there would be no serf labor of pupils, no rationing of food, no drudgery work.” Instead, he hoped “to improve the place with a high esprit de corps by supplying a good sports program and other entertainment.”[12] Staley did not abandon the farm, however. He recommended that the acreage that had been let out for sharecropping be brought back under the school’s control. He also made plans to raise mink and have the boys at the school make the pens as a manual training project.[13]

he academic side of the children’s schooling continued to suffer. In 1949, the inspector reported that emphasis was still placed upon practical training rather than academic learning, and that the children were in the classroom for only a part of the school day.”[14] The school also suffered from a shortage of senior teachers.

Principal Findlay Barnes abolished the half-day system in 1953 and ended the use of student labour on the farm.[15] In 1958, all farming at the school ceased, and both the farm animals and equipment were sold at public auction.

Post-WWII

World War II brought shortages and reductions in government spending at schools across the country as moneys and attention were diverted to the war effort. At Edmonton Residential School, neglect during the war years left the school in dire need of maintenance and cleaning, leading to poor water quality and to skin disease among the children. Principal Staley was so unhappy with the state in which he found the school, he delayed opening in 1946 to October, so that he could initiate changes and improvements to the facility. “The Indians who have such great opposition to sending their children there might change their minds, and do so freely,” wrote one inspector regarding Staley’s proposed changes.[16]

Staley arranged for a provincial sanitation inspection, which recommended a general redecorating of the facility, replacement of many wash basins and toilets because they had corroded past safe use, replacement of the septic tank and sewer pipes, improved drinking fountains, improvements to the fire escapes, and a complete new set of mattresses, as the old ones had become lumpy and uncomfortable.[17] The provincial sanitation inspector also recommended that two tubs be made available “to disinfect” new students at the beginning of each school year. School officials hoped these changes would make the school more appealing to communities and parents, who had often expressed dissatisfaction with the unhealthy conditions at the school.

These renovations did not, however, resolve all the school’s sanitation problems. A 1948 inspection reported only one toilet and no drinking taps in the dormitories and an overworked septic tank that created a foul-smelling pond of water.[18] By the 1950s, skin disease among the children was rampant. The new principal, Findlay Barnes, complained to the DIA about the shortage of washing basins: “This means that if one child has an infectious skin ailment, then many of the other children are apt to contract the same disease.”[19]

The end of the war also produced a shortage in staff as job openings and wages in the broader economy rose. Staley tried to woo better qualified staff with higher, provincial salary rates, but even these wages were not enough. By the time Barnes assumed the post of principal in 1952, all of the school’s employees, with the exception of the farming staff, had left, and he had great difficulty replacing them. “The small wages that he could offer attracted no one and his advertisements in the papers have brought no results,” the DIA inspector reported.[20] On reviewing the school’s operations, Barnes concluded that the school’s failings lay chiefly in the inadequacies of its staff. “Cheap, inefficient help has been its downfall,” he wrote. In the end the solution, in place by 1955, was to turn over responsibility for hiring teachers to the Department of Indian Affairs, something the United Church had been suggesting for years.

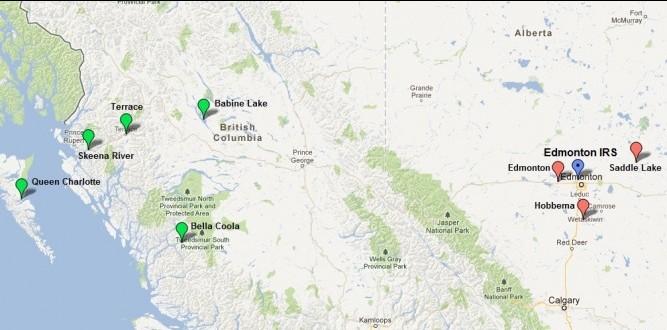

Recruitment from British Columbia

Edmonton Residential School originally recruited children from the Treaty 6 Cree communities with reserves in the vicinity of Edmonton—those of the Saddle Lake, Hobbema, and Edmonton Indian agencies. School officials soon discovered, however, that they could not achieve full enrolment (125 in the beginning and 150 after 1931) by registering children from these communities alone. The parents’ discontent with Red Deer Residential School and the transfer since its closing of children to other residential schools, appears to have contributed to low attendance.[21]

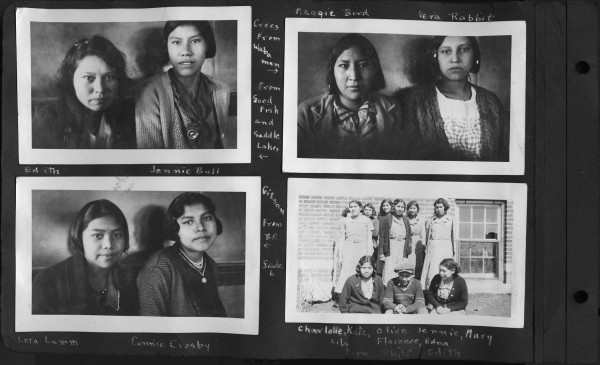

Between 1928 and 1937, to bring the school’s numbers to capacity, the school recruited children from Gitxsan and Tsimshian communities in northern British Columbia. Some 100 children from the neighbouring province attended during these years, accounting for almost one third of the student population.[22] From most accounts, these children suffered greatly. Distance, cultural differences, and the discrimination they felt they received at the hands both of administrators and of the Albertan students left them feeling particularly isolated and vulnerable. “All the B.C. boys hate this place,” wrote one student. “All the B.C. boys and myself don’t like what we are eating in our dining room, we couldn’t hardly eat anything, because we are not used to them kinds of food.”[23]

Parents protested against the great distances their children had to travel, the school’s emphasis on farming—unsuitable, they reasoned, for children from fishing communities—and the unfamiliar food. Both the DIA and Principal Woodsworth noted but in the end dismissed these complaints. “I fancy food is about the same in Alberta as in B.C.,” Wordsworth wrote to the DIA. “If fish were more plentiful we might give them some more frequently, but as it is we have it in season.”[24] For its part, the DIA responded to the expense of sending the B.C. children home during the holidays by suspending holidays for them altogether.[25] Many parents did not see their children for years.

Community protests against the practice of sending children out of province did not diminish, and by 1937, the DIA recommended ending it.[26] G.H. Barry, district inspector of Indian Schools for British Columbia, observed, “I am very unhappy with regard to the lack of progress made by the Indian pupils going to the Residential School near Edmonton. I am told that the B.C. Indians are quite out of touch with various activities there as they are not considered by the Indians on the Alberta side of the Rocky Mountains as of the same stock.” Barry considered the Anglican residential school at Alert Bay, on Vancouver Island, a better option for these children.[27] Principal Woodsworth accepted the DIA’s recommendation, noting that the great distance between school and home had caused much friction between parents, the Indian Agent, and Ottawa.[28]

By the late 1940s, most of the children attending Edmonton Residential School were again from the Hobbema, Saddle Lake, and Edmonton Indian agencies, with occasional students being placed from other schools in the province or from Saskatchewan when schools were closed or overcrowded. Keeping enrolment at capacity continued to be a struggle. Many families preferred the new day schools located in First Nations communities throughout Alberta. For a time, government officials suggested converting Edmonton Residential School into a non-denominational school under government management, but church officials resisted: “The United Church of Canada will not abandon the Edmonton school.” [29]

Another solution explored was recruitment of 60 to 80 children who could not be accommodated at the Morley Residential School, located on the Stoney reserve near Calgary. The Stoney, however, had always refused to send their children away from the reserve. Assurances were made to Stoney parents that their children would get “first-class academic training and be relieved of chores which would retard their school progress.” Officials also threatened to use “compulsion.” [30] But the Stoney stood firm. Few of their children ever went to Edmonton.

Once again, the DIA turned to northern British Columbia to make up the shortfall, relocating children from day schools and from Alberni Residential School, on Vancouver Island. The DIA’s educational survey officer claimed the Edmonton school was more accessible for communities in the Hazelton region of British Columbia. Travel to Alberni required a lengthy train ride, a treacherous three-day ocean voyage, and a final overland journey. Sixty children from Tsimshian and Gitxsan communities began the school term at Edmonton Residential School in September 1950.[31]

To accommodate the newcomers, the school added a sixth, full-day classroom. In addition, since many of the recruits were affiliated with the Anglican Church, the school agreed to provide some Anglican services.[32] From 1950 to 1968, children from Babine Lake, Skeena River, Haida Gwaii, Terrace, Wuikinuxv (known at the time as Oweekano), Kitasoo, Bella Bella, and Bella Coola made up most of the school population. In 1958, for example, 120 students at Edmonton Residential School were from northern British Columbia. Half of these children were affiliated with the Anglican Church and half with the United Church. The remaining 24 students were from Alberta.[33] In 1955, there were also two Inuit children registered.[34]

Not surprisingly, the friction described by Woodworth during the 1930s soon resurfaced. According to Principal Staley, the older B.C. boys were “a bad lot.” Similarly, Oliver Strapp, who was principal from 1955 to 1960, reported that staff had difficulty handling the older students. He wrote also of “a definite antipathy” between the B.C. and the Alberta students.[35]

Recruitment from British Columbia continued. In October 1960, the DIA sent Grade 7 and 8 children from the Gitxsan villages of Gitwangak (also known as Kitwanga), and Gitanyow (known at the time as Kitwancool) to Edmonton, citing the poor quality of the teaching at the local day school. Their parents were very reluctant but finally let them go on the promise that they would return for the Christmas holidays. In the meantime, they petitioned to have their children integrated into the public school system at home. Despite DIA and church opposition, the children returned to the Kitwanga Valley in January 1961 and joined the Kitwanaga Valley Public School.[36] In their petition, the Kitwancool Council cited the “unfavourable rumours” they’d been hearing for years about Edmonton Residential School, the abuse that children were subjected to by other students, and “immorality” at the school.[37] One student had written to her mother, “Please send for us if you do not want us to come home in caskets.”[38]

Allegations against the School

Negative reports and “harmful stories” about Edmonton Residential School abounded, but for a long time, church officials maintained that they were exaggerated or false.[39] Then, E.F. Stotesbury, a missionary from Saskatchewan, reported to church officials his suspicion that the school’s minister, James C. Ludford, was sexually abusing students. On September 28, 1960, Ludford was convicted on charges of gross indecency and received a one-year suspended sentence with psychiatric treatment. The next month, Stotesbury brought further reports of sexual misconduct, this time among the students, to the attention of church authorities. Shaken by the revelations, Superintendent of Missions Etude declared that staff incompetence at the school was beyond comprehension, the church was losing the confidence of Indigenous peoples, and that they were becoming the laughing stock of their Catholic counterparts. He concluded, “It is now apparent that our Indian people knew of this situation long before the church was aware of it.”[40]

The Cemetery at Edmonton Residential School

Around 1946, the Indian Affairs Branch asked for space on the school property to establish a small graveyard to bury First Nation and Inuit individuals who had passed away at the nearby Camsell Hospital and whose northern homes were considered too distant for their return for burial.[41] In 1965, the Edmonton Indian Agency Superintendent clarified that deceased individuals from Alberta and the Northwest Territories, whose families could not pay for their return home, had been buried in the cemetery.

Although the cemetery was under the jurisdiction of the DIA, officials noted that “spiritual sponsorship of the cemetery is under the United Church.”[42] They also relied on students at the school to help with maintenance. For instance, Principal Barnes wrote in 1955, “The boys at the School keep the grounds in reasonable condition for no remuneration, but they get paid for digging graves.”[43]

The last burial at the cemetery occurred in 1966. After Edmonton Residential School closed, the province pledged to preserve and improve the site and erect a commemorative plaque or historical marker. The DIA recommended advising the Indian Association of Alberta and the descendants of the people, such as Chief Sun, who were buried there “to assure them that the old cemetery will be undisturbed as a result of the transfer of the land to provincial jurisdiction.”[44] The City of St. Albert became responsible for the graveyard’s care in 1979, after it annexed both the graveyard itself and land adjacent to the school property for a city cemetery.

In 1987, the Camsell Hospital History Committee erected a cairn at the site in memory of the Inuit and First Nation people interred there. Donald McBride, the last principal of Edmonton Residential School, was a member of the committee and compiled the list of names of the deceased.[45]

Integration and the Edmonton Student Residence

By the late 1950s, some DIA officials were calling for the closure of Edmonton Residential School. They argued that the school was not serving the interests of the Aboriginal communities from the region.[46] Importing children from British Columbia was expensive, and there was a growing preference among officials for placing students in foster homes from which they could attend day schools. In addition, the school building was in poor shape. “At present the accommodation is less than adequate and the atmosphere of the school is, to say the least, depressing,” commented the chairman of a committee struck in 1958 to determine the school’s future.[47]

At the time, Edmonton Residential School also boarded some 50 students who were attending public schools in Jasper Place, in the west end of Edmonton. Many of these students were very unhappy at the school due to the lack of a recreation program and the poor facilities.[48] It was difficult to accommodate these students elsewhere, however, because there were not enough foster homes in the Edmonton area.

In the end, the committee concluded that the school could run for the next three to five years, but that, with the current trend toward integrating Indigenous students into the public school system, the student population was bound to decline in the future. The committee agreed that farm operations at the school should cease, since this work occupied too much of the principal’s efforts. The United Church, for its part, continued to see the need for a residential school or hostel to serve the children who required institutional care. Plans were made to redecorate the Edmonton school and update the plumbing, wiring, heating, and kitchen facilities. Meanwhile, the DIA and the church investigated the possibility of establishing hostel accommodation to replace the residence.[49]

By June 1960, Edmonton Residential School had become, in effect, a student residence rather than a school, with all its boarders attending grades 3 to 12 in schools in Jasper Place.

Home Economics and Industrial Arts were eliminated and two teacher-advisors made up the entire teaching staff. In 1962, the residence was remodeled to accommodate 150 high school students who would attend high schools in the Jasper Place region. The United Church turned management of the residence over to the DIA at the end of the 1965/66 school year. Two years later, on June 30, 1968, the residence was closed.

Footnotes

- [?] to Mom and Dad, RG10, vol. 13463, file 901/25-1, pt. 1, 1950/10-1966/01, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). On the reverse of the page, the student wrote, “I wrote this in school and didn’t get to hear the new principal. And after hearing, I am inclined to try and stick out the rest of the year here.” ↩

- C.E. Manning, General Secretary, Missionary Society, and T. Ferrier, Superintendent, Methodist Missionary Schools, to D.C. Scott, Deputy Secretary General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), vol. 6350, file 753-1, LAC. ↩

- SGIA to D.M. Kennedy, M.P., Apr. 21, 1922, RG10, vol. 6450, file 753-1, LAC. ↩

- Ferrier to Scott, Sept. 12, 1924, RG10, vol. 6450, file 753-1, LAC. ↩

- M. Christianson, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to Harold McGill, Deputy SGIA, Feb. 26, 1933, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Christianson to McGill, Mar. 18, 1935, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- W.F. Graham, Indian Commissioner, “Edmonton School,” memorandum, Feb. 13, 1931, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Eddie Smith to Mr. Mortimer, Indian Agent, Oct. 18, 1931, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Mortimer to W.E. Ditchburn, Indian Commissioner for B.C., RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- J.F. Woodsworth to Secretary, Department of Indian Affairs (DIA), [Feb. 12?], 1932, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Graham to School’s Branch, DIA, Mar. 5, 1929, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- G.H. Gooderham, Acting Inspector of Indian Agencies, to Indian Affairs Branch, Aug. 7, 1946, file (110)774/6-1-753, vol. 1, 09.45-12/53, LAC. ↩

- E.J. Staley to Indian Affairs Branch, Dec. 12, 1946, RG10, vol. 6351, file 753-5, pt. 6, LAC. ↩

- R.J. Scott, Inspector of Schools, “Report of Inspections,” Nov. 10, 1949, file 701/23-5, 1947–1972, vol. 1 [Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC)]. ↩

- Gooderham to Director, Indian Affair Branch, Aug. 14, 1952, RG10, vol. 8757, file 709/25-1-001, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Gooderham to Indian Affairs Branch, Aug. 7, 1946. ↩

- J. Butterfield, Provincial Sanitary Inspector, “Edmonton Indian Residential School,” Sept. 21, 1946, RG10, vol. 6351, file 753-5, pt. 4, LAC. ↩

- Donald Inspection Ltd., “Report of Inspection of Edmonton Indian Residential School,” Sept. 30, 1948, RG10, vol. 6545, file 1A-1656-12, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Findlay Barnes, Principal, to H.N. Woodsworth, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Feb. 2, 1953, file (110)774/6-1-753, vol. 1, 09/45-12/53, LAC. ↩

- G.H. Gooderham, Regional Supervisor of Indian Agencies, to Director, Indian Affairs, Aug. 14, 1952, RG10, vol. 8757, file 709/25-1—001, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Graham to Scott, Sept. 17, 1926, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- For example, in 1933, sixty of the 150 children were from the Babine Agency in northern British Columbia. Christianson to McGill, Feb. 28, 1933, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Smith to Mortimer, Oct. 18, 1931. ↩

- Woodsworth to Secretary, DIA, [Feb. 12?], 1932. ↩

- T.R.L. MacInnes, Acting Secretary, DIA, to Woodsworth, Mar. 2, 1932, vol. 6350, file 753-1, LAC. ↩

- MacInnes to Woodsworth, June 19, 1937, RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Extract for Report of G.H. Barry, District Inspector of Indian Schools on his inspection of the Kitwanga Indian Day School, May 27, 1937,” RG10, vol. 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Woodsworth to Secretary, DIA, June 23, 1937, RG10, 6350, file 753-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Gooderham to Director, Indian Affairs Branch, May 30, 1950, RG10, file 772/25-1-01, 1949–1961, LAC. ↩

- Gooderham to Director, May 30, 1950. ↩

- Bernard F. Neary, Superintendent of Indian Education, to Rev. G. Dorey, Board of Home Missions, Aug. 30, 1950, RG10, vol. 6352, file 753-10, pt. 3, LAC. ↩

- C.A.F. Clark, Educational Survey Officer, to District Inspector of Indian Schools, Vancouver, June 20, 1950, file 971/25-2-5, pt. 1, 06/50-06/51, LAC (BC).↩

- L.G.P. Waller, Chair, “Minutes of a Meeting of a Committee formed to investigate the present and future roles of the Edmonton Residential School…” June 23, 1958, RG10, vol. 8757, file 709/25-1-001, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- H.S. Ridgeway to E.J. Blake, Sept. 29, 1955, RG10, vol. 8843, file 709/16-2-001, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Oliver B. Strapp to E.M. Joblin, Assistant Secretary, Board of Home Missions, Dec. 9, 1959, accession 1983.050C, box 112, file 17, United Church of Canada Archives (UCCA). ↩

- J. E. Inget, District Superintendent of Indian Schools, to Regional Office, Dec. 5, 1960, RG10, vol. 8791, file 984/25-11, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Inget to Regional Office, Dec. 6, 1960, RG10, vol. 8791, file 984/25-11, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Minutes of Meeting of the Indian School Commission of the Edmonton Presbytery,” Dec. 13, 1960, accession 1985.050C, box 112, file 17, UCCA. ↩

- G. Etude, Superintendent of Missions, to C. Dwight Powell, Oct. 25, 1960, access. 1983.050C, box 112, file 17, UCCA. ↩

- F. Barnes to G.S. Lapp, Indian Superintendent, June 8, 1955, file 709/36-4-001, 1949-1959, vol. 1, [INAC]. ↩

- S.C. Knapp, Superintendent, to Regional Director, Edmonton Indian Agency, Sept. 2, 1965, file 774/36-7, vol. 2, Alberta, [INAC]. ↩

- Barnes to Lapp, June 8, 1955. ↩

- F.L. Short, Education Services, DIA, to G.D. Cromb, July 2, 1970, file 774/6-1, vol. 1, 1964-1974, CR-HQ, [INAC]. ↩

- Elva Taylor, Chair, Monument Committee, to Hon. Nellie Cournyea, Apr. 25, 1989, accession 97.726, Provincial Archives of Alberta. ↩

- W.E. Frame, report, May 29, 1958, file 774(110)/6-1-753, vol. 3, 01/58-12/59, LAC. ↩

- Waller, “Minutes of a Meeting of a Committee.” ↩

- R.F. Battle, Regional Supervisor, memo to Indian Affairs Branch, Sept. 22, 1958, file 774/251, vol. 1, 1952-1966, RCAP. ↩

- Waller, “Minutes of a Meeting of a Committee.” ↩