Portage la Prairie Residential School

Dates of Operation

1888–1960 (Residential School); 1961–1975 (student residence)

Operated by the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Presbyterian Church in Canada and after 1925, by the Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) of The United Church of Canada. In 1969, the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) took over management of the residence.

Location

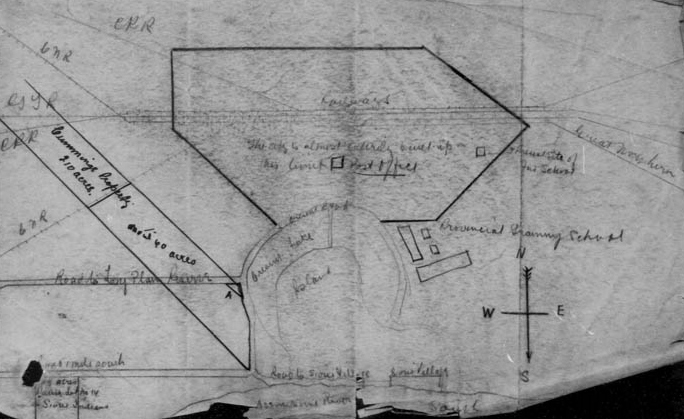

The first building was located one quarter mile east of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, but in 1915 the school moved to the shores of Crescent Lake, just southwest of the city.

On the day the four girls in question ran away, they had sent messages over a request program to their parents and expressed a wish to listen to the radio in order to listen to these messages. They were listening to the radio just before the program started and the radio was turned off and they were forced to go outside and play. I took this matter up with [the principal] Mr. Jones and he said, “They are better outside than listening to any old cowboy song.”

—R.S. Davis, Regional Supervisor of Indian Agencies, 1949, after four students

ran away from Portage la Prairie IRS and badly froze their feet[1]

The Sioux in Manitoba

When the U.S. government expelled the Dakota Sioux from Minnesota and abolished their reservations following the Dakota War of 1862, many Sioux families entered what is now Manitoba and settled in and around the town of Portage la Prairie. During the summer they lived in canvas tents on the eastern outskirts of town and in wintertime, they moved to log cabins on the banks of the Assiniboine River at a place that came to be known as Sioux Village.[2]

As settlers poured into the prairies, the Sioux, like other Indigenous peoples of the region, sought to secure a land base that would guarantee their survival. Representatives approached the lieutenant governor of the new Canadian province and asked for a reserve. The federal government, however, saw the Sioux as U.S. Native Americans without rights in the territory and did not want to cede any land to them before settling with the Ojibway people (also called Saulteaux, Anishinaabe, or Chippewa) of southern Manitoba. “[The Sioux] cannot justly be treated on the same footing as the Chippewas, Crees, and other tribes of the North-West, but it is open to doubt whether it is advisable to leave them entirely uncared for when the absence of game, the scarcity of grain, or other causes tend to reduce them to a starving and therefore desperate condition,” the Indian commissioner wrote in an 1871 dispatch.[3] After Treaty 1 was reached with Ojibway and Cree representatives, the government offered reserves to the Sioux, hoping they would leave their settlement in Portage la Prairie.[4] In 1874, some 1,500 Sioux people settled at Oak River (now Sioux Valley) and Birdtail Creek. Others went to Oak Lake or to Turtle Mountain (until 1911), and several groups settled in Saskatchewan.[5]

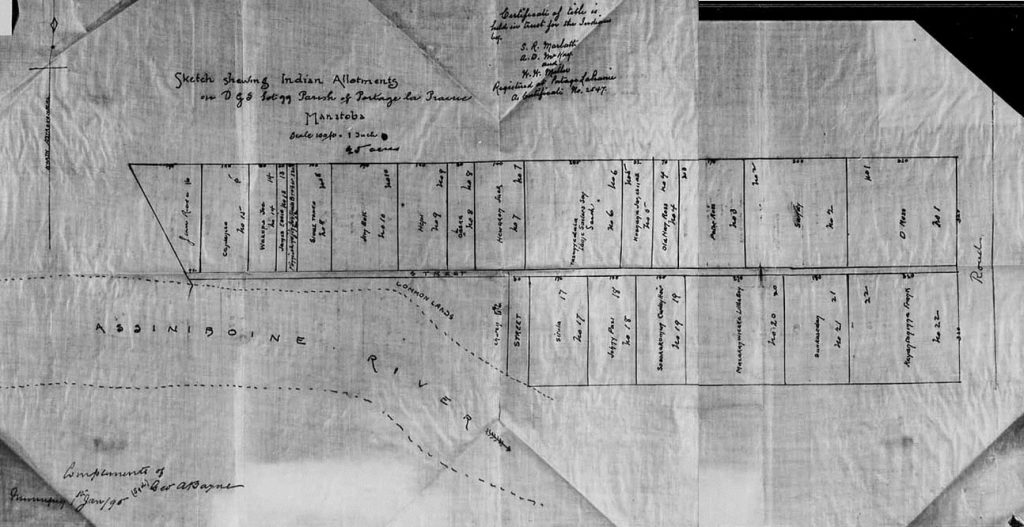

However, a number of families decided to stay in Sioux Village, where they could take advantage of the emerging settler economy. In 1893, they bought 26 acres of land there, using white settlers as proxies for the purchase.[6] The men of the village worked on the surrounding farms in the summer and cut wood in the winter. Women took work washing clothes, cleaning stores, and doing other odd jobs such as picking potatoes. Sioux people also grew their own vegetables to sell to the townspeople. Alongside these activities, they continued to travel the region to hunt and trap.[7]

The Boarding School

Although they hired and traded with both Sioux and Ojibway peoples, the European settlers of Portage la Prairie viewed the presence of Indigneous people in town with concern and hoped to convert them to Christianity. With this aim, in 1886 a group of ten women from Knox Presbyterian (now Trinity United) decided to open a day school for Sioux people, young and old, to receive lunch and an outfit of clothes, as well as lessons in a building they rented on the east side of town. “The lunch, which was mainly soup and bread or stew and potatoes proved a drawing card,” wrote Amanda MacKay, the group’s secretary. In the first year they reported attendance by 10 to 40 students of all ages.[8]

The women soon looked beyond Portage la Prairie for assistance with their project. The federal government refused to provide funding, arguing that placing schools for Indigenous children near towns or white settlements would induce other Indigenous people to leave their reserves: “If these Sioux Indians wish to have their children educated they have only to return to their Reserves [i.e., Oak River and Oak Lake] and give evidence of such wish.”[9] In the government view, Indigenous people living off-reserve would soon become “demoralized” and “a nuisance to white people.”[10]

The Women’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, based in Ontario, agreed to both finance and manage the school if it were made a residential school. For six months the Presbyterians in Portage la Prairie tried to recruit boarders without success: “Some were afraid to come even as day pupils, lest in some way they might be entrapped and become residents in spite of themselves.”[11] In the end, the women acquired their first student by convincing a Sioux mother to sell them her adoptive daughter, a six-year-old girl named Inkabah, for a dress and some other goods.

By 1888, other children were also living in the school, although, as Amanda MacKay observed, they did not like to stay for long and frequently left to be with their families. Sometimes, she wrote, “they just had to break away for a day.”[12] In addition to reading, writing and simple arithmetic, the children learned to mend clothes, clean house, sing, and play games. They were also taught bible stories and parts of the shorter catechism, although, MacKay noted, it was “not always intelligently understood.”[13] Day students as well as resident students were in attendance.

In 1890, with 26 students (day and boarding) enrolled, the government agreed to pay the teacher’s salary and, in 1891, issued the first per capita boarding school grant.[14] At that time, 17 children were enrolled as boarders and 16 as day students.[15] The day school ceased operations at the end of the 1892/93 school year.[16]

Recruitment

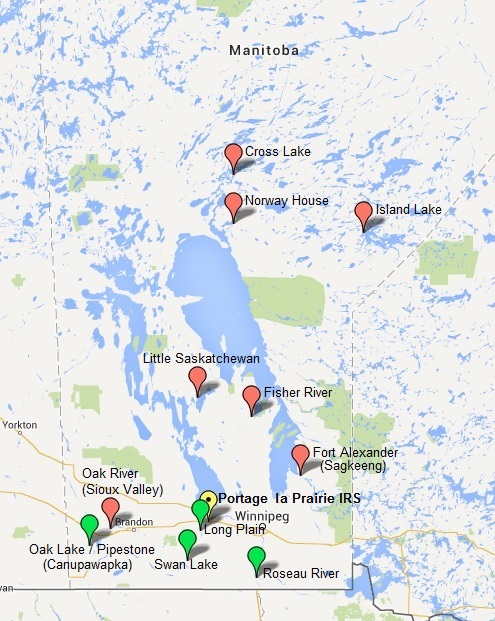

In addition to Sioux people, many Ojibway people lived in and around Portage la Prairie. In 1876, as signatories to Treaty 1, they were allotted reserves, and what had been known as the Portage la Prairie First Nation divided into three groups, settling at Swan Lake, Long Plain, and White Mud River (now called Sandy Bay).[17]

From its earliest years, Portage la Prairie Residential School tried to attract students from these communities, in particular from Long Plain, which was less than 10 kilometres away. In 1888, the teacher visited Long Plain for several days advertising the skills taught at the school and bringing gifts to the children:

She also took a little girl from the school at the Portage, whom she had neatly dressed and took her round to each tent with her and showed samples of her writing and made her read, thinking by this method she would stir up a desire among the women to have their children educated, but her efforts had no effect.[18]

This resistance lasted until 1908, when the first children from Long Plain enrolled “very much against the wishes and efforts of the old Indians there.”[19] Until then, government funds for the school had come from the parliamentary vote for the Sioux. A special grant from the general school vote was made to pay for the five new students.[20] From there Portage la Prairie Residential School increasingly enrolled students from other reserves in southern Manitoba so that by 1940, children were in attendance from the Ojibway communities of Long Plain, Swan Lake, and Roseau River, and the Sioux community of Oak Lake.

For the missionaries, having children in the school was a step toward gaining a foothold in the community. After a Presbyterian chapel was finally opened on the Long Plain reserve in 1923, for example, the general secretary of the Board of Home Missions wrote that their work “would have been a failure had it not been for the foundation laid in the character of the younger Indians by the work of the Indian Industrial school at Portage la Prairie.”[21]

Still, the Sioux of Portage la Prairie saw their claim on the school as greater than that of other First Nations. When the Presbyterian and Methodist congregations voted to unite in 1925, Sioux families who wished to remain Presbyterian petitioned the government “to have this school turn over to the Continuing Presbyterian Church where we can have our children there rather than for the poor youngsters to be sent away about 100 or more miles away, when we are living within a mile from the present school.”[22] They argued, “The Long Plain Indian Reserve are in favour with us and want us to make the appeal…They told us we have more say in the school settlement because we were the ones that started it, both church and school, 45 years ago with the Presbyterian Church.”[23] In further defence of their claim, the petitioners cited their sacrifices and loyalty during the Northwest Rebellion, the War of 1812, and World War I.

With the closure in 1946 of Norway House Residential School in northern Manitoba, Cree children began to attend Portage la Prairie Residential School as well. For a time Principal Jones brought in children from Island Lake and other distant communities against the explicit orders of the DIA.[24] By the time Portage la Prairie Residential School closed, however, children from across the province were in attendance with government consent.

A New Building and a New Location

Shortly after taking over management of Portage la Prairie Residential School , the WFMS built a new residence situated on an acre of land near the first, rented building.[25] Girls’ and boys’ dorms as well as a sick room and bathroom were upstairs, while the ground floor contained the children’s dining room and parlour, the kitchen, washrooms and teachers’ quarters. The schoolhouse was a separate but adjacent building, and at some point a playroom was installed in the space between the residence and the school and another acre of land was acquired.[26]

Originally deemed large enough to accommodate 40 children, by 1911 officials had reduced the recommended maximum to 25 children.[27] Staff had grown from two to four in the same period, and the garden and farm had expanded. Water was becoming scarce. After an inspector reported in 1910 that while “excellent work is being done at this school, the building and surroundings are unsatisfactory,” the DIA recommended selling the property and finding a new site.[28] As the Presbyterian Church declared itself unable to shoulder this burden, in 1913 the DIA bought 56 acres of farmland on Crescent Lake, southwest of the city, and built a new school there, with accommodation for 75 students.[29] Two years later, some 70 students and six staff moved in.[30]

Curriculum

At the school’s first location, students attended classes morning and afternoon, following the provincial course of study. Older students also learned to play musical instruments. Outside of the classroom, the girls did the sewing, cooking, laundry work, dairy work and general housework. The boys were taught gardening, caring for the stock and poultry, and by 1913, shoe repair. They also cut wood and helped with the whitewashing, painting, and general upkeep and repair of the school.[31] Recreation included skating, a variety of sports, skipping, swinging, and supervised walks. Religious devotion was conducted morning and evening, with Sabbath school on Saturday and church services on Sunday.

After 1915, at the new, larger building, the half-day system was adopted, with half of the senior students attending classes in the morning and the other half in the afternoon. The junior classes were large and difficult to manage, with a single teacher responsible for more than 40 students at as many as six different grades levels. “I do not think it is possible for any teacher to do justice to such a situation even in a school of white children,” one inspector wrote.[32] Meanwhile, the senior students were handicapped by the half-day instruction, which made educational progress “well-nigh impossible.”[33]

Vocational training remained minimal. In 1936, the Indian agent noted “few opportunities” available to the students in manual training and recommended construction of a carpenter shop.[34] And in 1943, the girls were “employed largely in scrubbing and the boys in farm chores.”[35] According to the visiting inspector, the children spent much of their time “on matters which should rightly be done by hired help.”[36] Farming became the focus of the school’s industrial training.

Farming

At the original school site, one of the two acres of land available was dedicated to growing vegetables. Principal W.A. Hendry wrote in 1903,

Each child is given some vegetable such as carrots, beets, peas, cabbage, etc., for which he is held responsible…They take a very keen interest in their work, and enjoy it better than any amusement the school can afford them. Each tries to surpass the other in growing the best vegetable. This year we have sixteen different kinds of vegetables, besides our potatoes.[37]

In 1908, Hendry added a stable to hold two cows and a horse, and the next year he added a chicken coop with 60 fowl.[38] Little more could be done, however, without acquiring more land, a fact DIA inspectors often lamented. “As a feeder for the industrial school, it is all that can be desired,” wrote one. “It is unfortunate that there was not more land in connection, as the staff is capable of imparting a much more extensive training.”[39]

With the arrival of Principal J.L. Millar in 1910, the school began to rent farmland. In his first year, the students raised 100 bushels of mangolds and two tons of corn. Millar also added another cow.[40] Two years later, the school had five acres under cultivation, producing 100 bushels of potatoes, 6 tons of cow fodder, 100 bushels of turnips, 200 bushels of sugar beets, and 25 bushels of garden carrots. The children had slaughtered one of the cows for beef and were raising a heifer calf. However, even when renting (in Millar’s words) “as many vacant lots as possible,” farming at the school remained insignificant compared to what awaited students at the new school site.

From the first year at the site on Crescent Lake, students kept all 56 acres under cultivation. Further acreage was purchased in 1919, and by the late 1930s, the farm comprised 176 acres, 130 of which were cultivated.[41] In addition to raising crops, the students kept 22 cattle, 4 horses, 23 pigs and 55 chickens. “The whole place looks more like an experimental farm than an Indian boarding school, and the beauty of it is that the work is all done by Indian boys,” wrote M. Christianson in 1925. According to Christianson, proceeds from the farm allowed Principal Hendry (in charge 1902–1909 and 1911–1934) to run the school at a surplus, with “several thousands of dollars to its credit.”[42]

Joseph Jones, who was principal from 1935 to 1942 and again from 1947 to 1949, had hoped to expand production further with another 100 or 160 acres across the lake, but the DIA refused, giving the argument that “the average Indian is a small farmer.”[43] The United Church also moved to curb Jones’ enthusiasm after he put the school into overdraft by replacing the herd of “grade cows” with the more expensive Jerseys and bought Percherons instead of “ordinary” farm horses. According to UCC officials, the ordinary horse was “more suited for such an institution, since the horses on the reserve are very ordinary indeed.”[44] Some DIA officials also questioned the effects of such intense training on the children. In 1949 after observing what he described as “large construction and Lumber and Fishing camps” at Portage La Prairie Residential School, regional supervisor R.S. Davis wrote, “Our schools should not be classed or run as a Construction or Fishing Camp, but be a real home for the children!”[45]

Farming continued at Portage la Prairie Residential School until 1961, when the school was converted into a student residence and the government designated 163 acres of its holdings for other purposes. Forty-five acres were retained for the residence buildings and grounds.

Student Health and Welfare

Illness and epidemics occurred at Portage la Prairie, as they did at all residential schools, and children died, usually from tuberculosis. Whether through good luck or good management, Portage la Prairie Residential School made it through the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic with no cases reported. When the disease hit the neighbouring town, the local Indian agent asked the DIA for permission to send the children home. He argued they “would have a better chance in the open then [sic] they would closed up to-gether.” [46] He also noted that if any children died at the school “the Indians would blame the authorities for not allowing their children to come home.”[47] By the time he got an answer, however, the children’s home reserves were already under quarantine. In the end, only 21 students (out of 75) went home. The rest remained at the school, with only the principal allowed to come and go.

The presence, starting in 1915, of a trained nurse on staff may have helped the school during such crises as well as on a day-to-day basis. The DIA paid the nurse’s salary until 1925, after which she was paid from the school’s per capita grant.[48]

Conditions at the school were not always good, however. Staff often found it difficult to keep the place warm enough during the winter.[49] And there were problems with the septic tank, which would back up into the school and, since it emptied into Crescent Lake, created a great stench for both the school and the neighbouring townspeople.[50]

From the earliest days, children also ran away, sometimes with dire consequences. In 1949, for example, four girls ran away in the dead of winter and suffered serious injuries to their feet. The DIA investigation that followed discovered that Principal Jones had adopted several questionable measures to control the children: the school made an example of girls who went truant by “bobbing” their hair; children were not allowed to speak during mealtime; brothers and sisters were allowed to converse only “by request and then only in the sitting room”; incoming and outgoing mail was censored; all doors were kept locked; staff would pull the children’s hair and hit them on the head with their knuckles; and both staff and the principal applied the strap frequently.[51] Jones was removed as principal.[52]

But truancy did not diminish. In 1950, the principal reported that it had become “epidemic.”[53] And in the fall of 1964, after the school became a residence for older students only, almost 20 percent of the school population ran away. Officials blamed the withdrawal of so many students on “institutional life with its necessary regimentation” and looked for ways to make the residence more appealing.[54]

The Student Residence

In 1957, the DIA and the United Church agreed on a major reorganization of both Brandon Residential School and Portage la Prairie Residential School—the only two United Church residential schools left in the province. The schools’ combined student population was divided into younger, elementary students, who would attended Brandon Residential School, and older students (grade 6 and above) destined for Portage la Prairie Residential School. The latter school also began to integrate some of its older boarders into schools in the city, the DIA purchasing space for them in the public system. The first 25 began attending high school there that year.[55]

Gradually integration increased, until in 1961 Portage la Prairie Residential School closed its last classroom. At the time 129 children were attending public schools in the city.[56] For the next 14 years, until it closed, Portage la Prairie Residential School was a student residence only.

Although they received their classes in town, students continued to receive support at the residence from “teacher-advisors” whose job it was to organize their study program, supervise their studies, give guidance, keep their student records and act as liaisons with the city schools. “Many of these pupils, coming as they do from remote, isolated areas where they had little contact with the non-Indian culture into which they have been plunged on enrolment in a non-Indian school, require assistance not only to make the necessary emotional and social adjustments, but also to keep up with their academic studies,” the DIA reasoned.[57] Also starting in 1961, some 20 students were boarded in private homes in Portage la Prairie. Although they did not live in the residence, these students continued to be supervised by the teacher-advisors.[58]

According to one newspaper article, integration went beyond the classroom:

Today, seniors at the residence spend Saturdays working in stores, gas stations, private homes, the post office and workshops in the city. They run dances which have become important dates in the city’s social calendar for teenagers, white and Indian. They worship at the same churches as the white man, and have athletic teams which compete with the white man’s teams.[59]

In 1965, major renovations were made to the buildings and the institution’s name was formally changed to the Portage Student Residence. Only high school students lived there. To better accommodate this age group, Principal J.O. Harris had the residence’s large, open dormitories converted to “self-contained roomettes fully equipped with personal clothing wardrobe, vanity and student facilities for two students.”[60] A new recreation room, a library and a self-serve lunch counter were also installed. The aim of the renovations, according to Harris, was to provide a more casual atmosphere where students would learn responsibility and independence. “Gone with the dormitories are the marching lines of students and the impersonal call of the bell,” the local paper reported. “[Students] will have the opportunity of choosing (with guidance) their own clothing and the accent on everything from clothing to the colour of the new drapes and spreads will be placed on individual taste and the lack of uniformity.”[61]

Harris was an “active public relations man” and used extra-curricular activities as a way to raise the residence’s profile. [62] Local media covered the triumphs of its sports teams, and the glee club, formed in 1966, toured widely in Canada, the United States, and Europe. However, in a letter regarding complaints about the treatment of students in residence and, in particular, the glee club, the district superintendent of schools concluded that the singing group was “not so much a relaxing extracurricular activity for the students as a means of bringing glory to the Residence and its Administrator.”[63]

In 1970 the DIA took over management of the three remaining Student Residences in the province. Enrolment at the Portage la Prairie residence had dropped to 60, which was 20 less than capacity. By 1975, enrolment was 39. DIA reports identified three factors contributing to the sharp decline: parents preferred to keep their children at home; high school courses were available in many communities; and students preferred to board in private homes rather than residences. In 1975, after consulting with the chiefs and councils of the affected communities, the decision was made to close at the end of the school year. The students remaining in residence (20 of them from Norway House) were placed in private homes.[64]

Today

In 1980, the 45-acre residence site and its buildings were transferred to the Long Plain First Nation as Treaty Land Entitlement stemming from a Loss of Use Claim, and in 1982, the land became Long Plain Indian Reserve No. 6. In 2003, the Long Plain First Nation launched a project to install a museum of Residential School history there, with projections for opening in 2008, but funding fell through.[65] The building was designated a Provincial Heritage Site in 2005.[66] It is now used as a resource centre, housing offices for the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council, and Long Plain First Nation.

Footnotes

- Davis to D.M. McKay, Superintendent of Welfare, Indian Affairs Branch, and enclosed statements, Mar. 4, 1949, vol. 1, file 501/25/1/067, Residential Schools Records Office (RSRO), Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). ↩

- Angus D. MacKay to Rev. Principal Grant, Kingston, Jan. 10, 1894, PP90, file 3283, United Church of Canada (UCC) Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Wemyss M. Simpson, Indian Commissioner, to Secretary of State for the Provinces, Nov. 3, 1871, Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual reports, 1871, pp. 27–32. ↩

- Alexander Morris, Lt. Governor, to Secretary of State for the Provinces, Dec. 13, 1872, DIA annual reports, 1872, pp. 12–13. For further correspondence regarding the Sioux reserves, see RG10, vol. 3603, file 2118, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). ↩

- Roy W. Meyer, “The Canadian Sioux Refugees from Minnesota,”Minnesota History 41 (Spring 1968): 13–38. The Dakota Sioux nations of Manitoba (Birdtail Sioux, Sioux Valley, Canupawakpa, Dakota Tipi and Dakota Plains) are not signatories to treaties with Canada. The federal government continues to oppose Dakota Sioux claims to Aboriginal rights in the country. For an outline of this claim, see Teyan Neufeld, “Dakota Claim in Canada,” 2010, Turtle Mountain–Souris Plains Heritage Association. ↩

- S.R. Marlatt, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to David Laird, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, May [3?], 1907, RG10, vol. 3569, file 95, pt. 29, LAC. ↩

- In 1972, the village disbanded and divided into two groups: one, called the Dakota Plains First Nation, relocated to land bordering the Ojibway Long Plain reserve, and the other, the Dakota Tipi First Nation, moved to just west of Portage la Prairie. See Dakota Tipi First Nation, “History.” ↩

- Amanda N. MacKay, “Notes on the Early History of the Indian Residential School Portage la Prairie,” n.d., PP90, f. 3282, pp.4–6, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- E. McColl, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to James Robertson, Superintendent of Presbyterian Missions, July 13, 1886, RG10, vol. 6029, f. 127-4-1, LAC. ↩

- McColl to Robert Watson, MP, July 12, RG10, vol. 6029, f. 127-4-1, LAC. ↩

- A.N. MacKay, “Notes on the Early History,” pp. 7–8. ↩

- Ibid, p. 8. ↩

- Ibid, p. 9. ↩

- DIA annual reports, 1890, p. 228 and pt. 2, p. 57; DIA annual reports, 1891, pt. 2, p. 49. ↩

- 15. DIA annual reports, 1891, p. 234. ↩

- “Portage La Prairie Boarding School” (memo, c. 1904), RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Swan Lake First Nation; Long Plain First Nation, “History.” ↩

- Francis Ogletree, Indian Agent, to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), Aug. 21, 1888, DIA annual reports, 1888, pp. 44–46. ↩

- S. Swinford, Inspector, to Secretary, DIA, Nov. 19, 1908, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- 20. J.D. McLean, Secretary, DIA, to David Laird, Indian Commissioner, Dec. 16, 1908, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- J.H. Edmison, General Secretary, Board of Home Missions, to Duncan C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, Oct. 17, 1923, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Peter Ross et al (petition), Feb. 17, 1927, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- A.G. Hamilton, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to Indian Affairs Branch, Oct. 1, 1947, RG10, vol. 6275, file 583-10, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- A.N. MacKay, “Notes on the Early History,” p. 6. ↩

- “Sioux Boarding School, Portage la Prairie, Man.,” DIA annual reports, 1898, pp. 303–305. ↩

- Compare, for example, Annie Fraser, Principal, to SGIA, July 15, 1897, DIA annual reports, 1897, pp. 240–241, and “The Report of J.L. Millar, Principal of the Portage la Prairie Boarding School, Portage la Prairie, for the Year Ended March 31, 1911,” DIA annual reports, 1911, p. 538. ↩

- Secretary, DIA, to R.P. Mackay, Foreign Mission Committee of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, May 10, 1910, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- The DIA bought almost 50 acres from the estate of Margaret Cummings and supplemented this with two smaller purchases, bringing the total acreage to approximately 56. See F.G. Taylor to Secretary, DIA, June 25, 1913; “This Indenture,” July 3, 1913; “Agreement,” Aug. 25, 1913; and “This Agreement,” Sept. 15, 1913—all in RG10, vol. 6275, file 583-9, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Portage la Prairie Boarding School (Presbyterian),” DIA annual reports, 1916, pp. 213–214. ↩

- “The Report of W.A. Hendry, Principal of the Portage la Prairie Boarding School, Portage la Prairie, Man., for the Year Ended March 31, 1913,” DIA annual reports, 1913, p. 557.↩

- B. Waikentin, Inspector of Public Schools, RG10, vol. 8449, file 511/23-5-017, LAC. ↩

- Eldon F. Simms, “Inspector’s Report,” Nov. [19?], 1943, RG10, vol. 8449, file 511/23-5-017, LAC. ↩

- [illeg.], Indian Agent, “Agent’s Report,” April 1936, RG10, vol. 8449, file 511/23-5-017, LAC. ↩

- Simms, “Inspector’s Report.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- W.A. Hendry, Principal, to SGIA, July 1, 1903, DIA annual reports, 1903, pp. 339–340. ↩

- Hendry to SGIA, Apr. 1, 1908, DIA annual reports, 1908, pp. 310–311; “Portage la Prairie (Sioux) Boarding School,” DIA annual reports, 1909, p. 319. ↩

- Marlatt, “Portage la Prairie Boarding School (Presbyterian),” DIA annual reports, 1906, pp. 356–357. ↩

- “The Report of J.L. Millar.” ↩

- H.R. Phillips, Lands Administration, to Director of Operations, Indian and Eskimo Affairs, Oct. 17, 1977, vol. 16, file 501/25-13-082, RSRO, DIAND. ↩

- M. Christianson, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to W.H. Graham, Indian Commissioner, Sept. 11, 1925, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Hamilton to Harold W. McGill, Director of Indian Affairs, Jan. 21, 1937, RG10, vol. 8449, file 511/25-3-017, LAC. ↩

- [J.A. Cormie, Superintendent of Home Missions], to Mrs. C.M. Loveys, May 11, 1939, box O, file 509/2/2-10, no. 6, UCC Praire to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Davis to D.M. MacKay, Indian Affairs Branch, Mar. 7, 1949, vol. 1, file 501/25/1/067, RSRO, DIAND. ↩

- Ogletree to Scott, Oct. 22, 1918, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- IIbid. ↩

- Scott to Andrew Grant, General Superintendent of Home Missions, Jan. 7, 1915, and Scott to Ogletree, May 28, 1925, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- See, for example, Hamilton to R.A. Hoey, Indian Affairs Branch, Jan. 11, 1937, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-5, pt. 5, LAC; and T.S. Mills, Chief Engineer, to J.M. Wardle, Director, Surveys and Engineering Branch, Jan. 15, 1947, RG10, vol. 6502, file IND 13-1-78, LAC; A.G. Leslie, Regional Supervisor, to Chief, Education Division, Indian Affairs Branch (memo, Jan. 19, 1960), RG10, vol. 8630, file 511/6-1-017, pt. 9, LAC. ↩

- Joseph Jones, Principal, to A.F. MacKenzie, Secretary, DIA, Feb. 25, 1936, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-5, pt. 5, LAC; Chief Sanitary Inspector, “Report of Special Inspection,” Feb. 21, 1936, RG10, vol. 6273, file 583-5, pt. 5, LAC; D.B. Gow, District Chief Engineer, to Mills, Apr. 25, 1942, RG10, vol. 6502, file IND 13-1-78, LAC; Leslie to Chief. ↩

- Davis to D.M. McKay, and enclosed statements, Mar. 4, 1949; Jones to Hamilton, Feb. 28, 1949; and Davis to D.M. MacKay, Mar. 7, 1949—all in vol. 1, file 501/25/1/067, RSRO, DIAND. ↩

- In November 1946, another principal, probably A.C. Huston, was removed at the DIA’s insistence, but research has not yet turned up records that indicate why. See Bernard F. Nearly, Superintendent of Education, to Director (memo, Mar. 16, 1949), vol. 1, file 501/25/1/067, RSRO, DIAND. ↩

- [illeg.], Indian Agent, “Agent’s Report,” February 1950, RG10, vol. 8449, file 511/23-5-017, LAC.↩

- J.M. Slobodzian, for R.M. Connelly, Regional Supervisor, to Director, Education Services (memo, Dec. 18, 1964), RG10, vol. 8631, file 511/6-1-017, pt. 13, LAC. ↩

- “Where Integration’s a Way of Life…Indian School Leads the Way,” The Daily Graphic, Mar. 11, 1954, 509/2/2-10, file 7, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives.↩

- DIA annual reports, 1961, p. 85. ↩

- Ibid., 1960, p. 56. ↩

- N.K. Campbell, [Board of Home Missions], to Gordon Waddell, Mar. 27, 1961, 509/2/2-10, file 7, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- “Where Integration’s a Way of Life.” ↩

- “Indian Residence Undergoes Facelift,” The Daily Graphic, Aug. 14, 1965, 509/2/2-10, file 7, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- E.E. Joblin, “Portage la Prairie” (material compiled March 1981), accession 1986.158C, box 2, file 7, page iii, UCCA. ↩

- J.R. Wright, District Superintendent of Schools, to Regional Superintendent of Schools, Feb. 10, 1969, vol. 3, file 501/25-13-067, RSRO, DIAND. ↩

- R.D. Brown, Regional Director, Indian and Eskimo Affairs, to All Chiefs and Councils, Feb. 21, 1975, vol. 1, file E-1974-5602, RSRO, DIAND. ↩

- The Manitoba Historical Society, “Indian Residential School Museum of Canada,” n.d.; CBC News, “Portage Residential School Museum in Works,” Aug. 21, 2006. ↩

- The Manitoba Historical Society, “Historic Sites of Manitoba: Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School (Crescent Road West, Portage la Prairie).” ↩