Norway House Residential School

Norway House Residential School Timeline

Dates of Operation

1900–1946, 1952–1965

Operated by the Missionary Society of the Methodist Church (Canada), and, after 1925, by the Board of Home Missions of the United Church.

Location

In central Manitoba on approximately 40 acres of Norway House No. 17, at Rossville. The reserve is on the shores of Little Playgreen Lake, about 40 kilometres north of Lake Winnipeg.

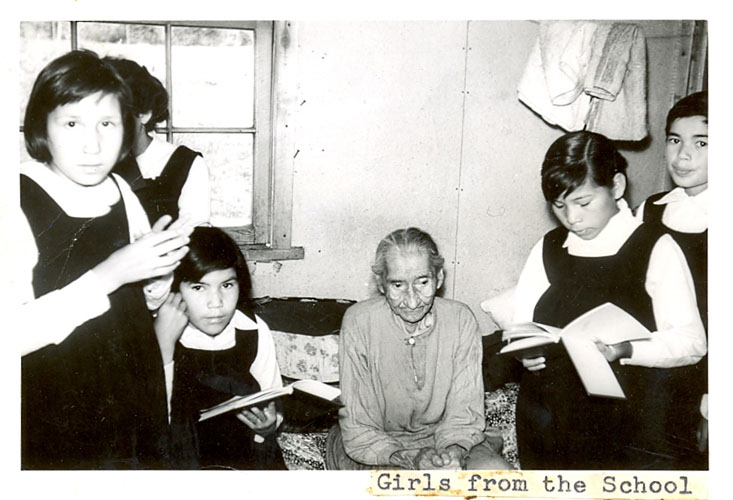

We spent many hours out-of-school with the children—planning and carrying out special events, teaching Sunday school, leading groups such as Mission Band, Explorers, and C.G.I.T. [Canadian Girls in Training]. We took turns leading morning chapel. I loved taking the children on field trips in the surrounding bush—they taught me so much about the environment that was so familiar to them. Often we built a fire and toasted marshmallows.

—Margaret Anne Reid recalls her two years as a young teacher at Norway House.[1]

Establishment

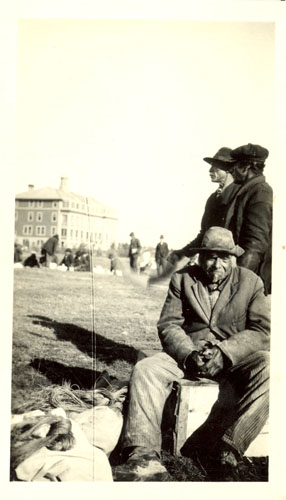

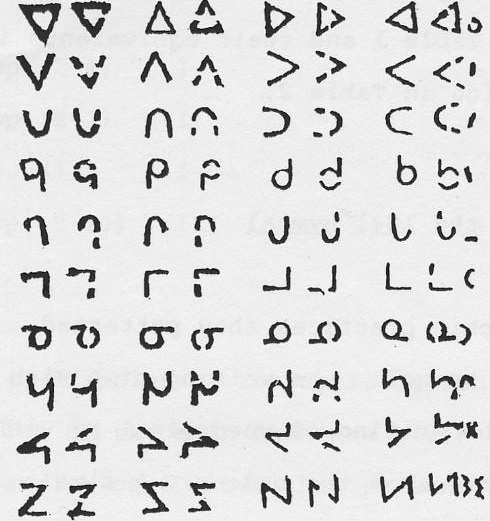

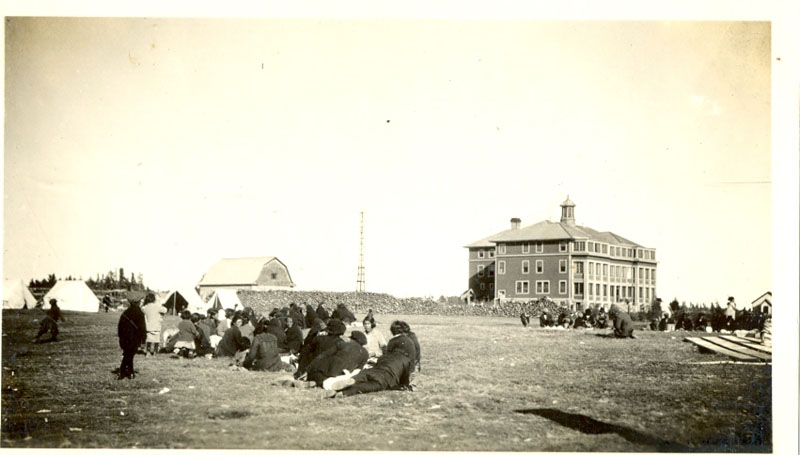

In 1840, Rev. James Evans, of the Methodist Church, established a mission at Norway House, on Little Playgreen Lake in central Manitoba. Just across the bay was a Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) post, a regional hub that collected furs from the company’s extensive Manitoba network and sent them on to York Factory on Hudson Bay for export. Swampy Cree families of the region, many of whom worked as trappers and shippers for the HBC, were drawn to Norway House as well, and by the 1860s they had a large and prosperous settlement there.[2]

However, the introduction of steamships on the Red River and Lake Winnipeg redirected goods away from York Factory and soon led to Norway House’s decline in the regional trade network. Facing resource depletion as well, the Norway House community, whose lands would not serve for farming, petitioned for a reserve further south. Together with other Cree people of the area they sought a treaty with the federal government.

Treaty 5, negotiated in 1875 with the Cree and Saulteaux nations living around Lake Winnipeg, established reserves, payments of annuities, distribution of agricultural equipment and medical supplies, the continued right to hunt, fish and trap on lands covered by the treaty, and education.[3] As part of the agreement, an initial group of some 200 Norway House people relocated to Fisher River, on the southeastern shore of Lake Winnipeg, but many others remained on the reserve established at Little Playgreen Lake.

Reverend Evans had opened a day school for about 25 students at Norway House soon after he established his mission, with the aim of teaching the children to read both English and their own Indigenous languages.[4] However, it was not until 1898 that the Methodist Church requested funds from the federal government to build a boarding school at the location. The residence would serve the numerous Indigenous communities in the region, many of whom did not wish to send their children as far away as Brandon Residential School, in southern Manitoba. The Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) approved funds towards construction of a residence and a per capita grant of $75 to a maximum of 50 students.[5]

The residence opened in the fall of 1900 with a staff of three and took in 56 boarders its first year. As part of their vocational training, the boys cut wood, fetched the school’s water from the lake, tended the vegetable garden, and helped in the kitchen and with baking. “As they are mostly small, they are really unable to do very heavy work,” wrote the school’s first principal, E.F. Hardiman.[6] The girls were taught plain and fancy sewing, dressmaking, baking, ironing, and washing. They also performed other housework and did all the mending. In later years, the boys cared for the school’s cattle and learned some carpentry.

The children took their academic classes in the day school along with 50 to 60 day students from the local community, a situation that led to overcrowding in the classroom and overwork for the lone schoolteacher.[7] After a schoolroom was built for the residence in 1903, senior students took their classes there, but the junior residents continued to attend the day school.[8] By that time, the boarding school staff numbered six.

Fire, 1913

By 1910, the Norway House residence was in bad repair, and school officials began to look for a new site to rebuild. A DIA surveyor sent to assess the situation was taken aback by the state of the building. He reported that the cellar was flooded and the building had poor insulation, but most serious was the risk of fire: “There is a continuous draft between the walls and were a fire to start the whole thing would be in flames in a few minutes. As the windows in the sleeping dormitories are barred I do not see how the children could be saved. The danger is great as no less than 13 stoves are in use in different parts of the building in winter.”[9]

Despite this warning and despite the Norway House First Nation’s surrender in 1910 of 40 acres of their reserve at Rossville as a school site, construction of a new building was postponed. On February 26, 1913, as predicted, the school burned to the ground in a fire started by a wood-burning stove. Luckily, according to reports, there were no injuries or lives lost. The resident students, who numbered around 50, continued to receive classes, billeted in local homes, the empty hospital, and the HBC store until a new residence could be constructed.[10]

That building, designed to accommodate 80 students, opened on October 15, 1915. Ninety-two students enrolled the first year.[11]

Student Recruitment

Initially, recruitment of students for Norway House Residential School focused on Norway House itself and the surrounding but still remote communities of Cross Lake, God’s Lake, Oxford House, Island Lake, Poplar River, and Berens River. In later years, however, dissatisfaction with the boarding school in a number of these communities forced recruiters to seek students from farther afield, in particular Nelson House, Split Lake, and Fox Lake, but also the very distant communities of Churchill, Shamattawa, and Trout Lake, Ontario.[12]

The school’s second principal, Rev. J.A. Lousley, was a particularly keen recruiter, which may in part explain his frequent absences from the school. Although the residence was built for 80 students, he worked to reach an enrolment of 100.[13] As a result, the school was overcrowded (in 1916, students were sleeping two to a bed), and the day school was saddled with absorbing the students who could not fit into the boarding school’s two classrooms.[14] The children’s health suffered, and provisions of food and clothing were sometimes insufficient.[15] Under Lousley’s successors, authorized enrolment increased even further, to 100 in 1922 and 105 in 1923. And in 1925, the school petitioned the DIA, unsuccessfully, to increase enrolment to 110.[16]

Conditions at Norway House led at least one community to withdraw their children from the school altogether. In the winter of 1915/16, nine children from Berens River arrived home showing signs of frostbite and complaining that they had been fed rotten fish.[17] When Chief Jacob Berens accused the school of breach of contract and refused to send more children until conditions had improved, Lousley rebuked him: “You have long hindered the children of your people from attending these great schools that God has provided for your people . . . So I, one of the men God has sent to you people in this North Land, call you to repent of this your wrong doing before it is too late.”[18] In his reply, Berens wrote, “I am glad I will eventually be judged by a higher judge than yourself,” and severed all ties to the school until Lousley was removed—which he was, in July of that year.[19]

Children generally travelled to Norway House by canoe, even when air travel, which the DIA considered too expensive, became available. Travel to Island Lake—not the most distant of the communities—took eight days, exposing the children “to the possibility of wet weather and colds” and leaving them in poor shape to start school, according to Principal R.T. Chapin.[20] Travel to and from the school also ate up a good part of the children’s two-month summer holiday. However, when administrators in 1935 complained, the DIA proposed simply keeping the children at school year round.[21] Eventually, children were flown in, with a teacher escort, on Norseman bush planes.[22]

Discipline and Truancy

From the outset, the school administration found truancy a problem. Principal Hardiman, who lasted only a year in his post, asked the DIA to enforce attendance: “I urge the necessity of bringing into operation laws that will enable the Principal of this school to be supreme in his work in the school, and not to be openly defied by certain members of the Band without having the least chance of redress.”[23] Eight years later, after noting that 13 students were absent “because of some paltry notion of either the child or its guardian,” Principal Lousley made a similar plea.[24]

The insistence on retaining at Norway House Residential School children who were considered difficult or unhappy led to some of the more serious incidents of abuse reported there. In the winter of 1906/07, Charles Clyne ran away from the residence after a staff member punished him for wetting his bed and for allegedly stealing clothing. Clyne spent the night in a cabin in the bush with the result that both his feet froze and he was permanently disabled. During the subsequent investigation, Lousley admitted to having thrashed the boy himself many times—more than any other student. Lousley contended that Clyne “deserved all he received as he was the very worst pupil in the school.” [25]

The investigating inspector, in contrast, argued that a student considered “undesirable,” should have been given an early dismissal. In addition, the inspector concluded that the principal, who was often away, should take a more direct role in the supervision of his staff and the school in general; the school should have made more of an effort to find the boy after he went missing; and bedwetting should have received medical attention rather than punishment—a solution, the inspector added, that “might have been more in accordance with Christian methods.”[26]

The school’s methods were questioned a second time—in 1915 after the new residence opened—when Lousley had a boy tied up in order to prevent him running away. R.T. Ferrier, of the Methodist Missionary Society, defended the principal’s actions, arguing that “this was the only time that this was done, and it was during a time that the ice was rotten in the bay and they were afraid that his foolishness might lead him to run away over the ice, and thus lose his life.”[27] Again, the investigating inspector recommended the boy’s discharge.[28]

Principals did not always take such a hard line. In 1934, for instance, Rev. W.W. Shoup let an eight-year-old who was “a little inclined to brood for his parents” go with them for the year “to the bush.”[29] Shoup, however, had faced other allegations. In 1930, shortly after Shoup became principal, Arthur Felix, father of a 15-year-old boy at the school, accused Shoup of striking his son and dragging him to another room where he strapped him. Shoup denied the severity of the assault. The RCMP investigated and the case went to trial in January, at which time the judge dismissed the charge and warned the principal to punish with a strap. The investigating officer noted that since Shoup’s appointment the previous summer, he had heard different stories of the principal’s harshness toward the pupils.[30]

Rev. Shoup was dismissed in 1934. A letter written in defense of his administration noted, “He has mellowed in his view and actions as time goes on. He now has the goodwill of the community, and of the children—as far as is possible, he being the Principal.”[31]

Student Health

Rev. Shoup’s supporters credited him with improving the students’ health, which had long been a serious problem at the school.[32] In the school’s first 13 years, the rate of reported deaths at the school was 36 per 1000. During the next period for which records exist, 1933 to 1941, it dropped to 7 per 1000.>[33] The biggest killer was tuberculosis, the “great white plague,” which was rampant in northern First Nations communities. As Dr. E.L. Stone wrote of Norway House Agency in 1925, “Disease here means one malady, and one only, for all practical purposes. That is tuberculosis. Practically nobody dies of anything else.”[34] In 1906/1907, nine children at Norway House Residential School died of the disease.

Epidemics, which swept the school on a regular basis, made health matters worse. Lousley wrote, for example, in 1902, “We have suffered, in common with the reserve upon which we are situated, from a most virulent epidemic of whooping-cough, bronchitis and pneumonia; most suffering from all three diseases at the same time, and in addition, some had chicken pox.” Three children died as a result, but Lousley insisted that this “could not be taken to indicate unhealthy conditions in or around the school, as there were about sixty-five deaths on the reserve from the same cause.”[35]

Principal Shoup, however, saw room for improvement. “Studying the situation I am assured that the over-crowding of this school in the past accounts for the condition of many.” By reducing enrolment from 105 to 89, Shoup found that “we can maintain what appears to be a more sanitary condition.”[36] He promoted outdoor recreation and put the children on the half-day system, with classes in the morning only: “The afternoons are devoted to out door exercises. For the boys a course of regular military drill for upwards of one hour—and then football or some other healthful games—all under the Sr. teacher. The girls have been given the regular course of drill taught in Manitoba ordinary Day Schools.”[37] Shoup had a children’s slide and an outdoor rink built as well.

The presence of a hospital and medical staff in Rossville, sporadically before 1914 and permanently thereafter, may have also contributed to better student survival rates. R.T. Chapin, principal from 1934 to 1941, wrote in his memoirs, “It meant a great deal to us to have a resident doctor, hospital and nurses on the Indian Agency grounds so close to us. It was seldom we had any serious illness, but it was a comfort to know that if the doctor took a boy or girl to the hospital he was receiving the best care possible.”[38]

Malnourishment had been a source of concern at the school as well. The problem was particularly acute in 1914/1915, just after the new building opened, when administrators were caught without enough food supplies to see them through the winter.[39] After complaints from the children’s home communities, the DIA ordered an investigation. Inspector Bunn found that several children who had been brought to the hospital for treatment and “low physical condition” had improved considerably, if not completely, after receiving “proper nourishing food” there. He noted that the school provided little in the way of fatty foods, that the bread was poorly cooked, that they had few root or other vegetables, that two carcasses of beef was all the school had for the entire winter, and that “suckers” had been served at times instead of good fish.[40]

Hope Island Farm

G.F. Denyes, who replaced Rev. Lousley in 1916, appears to have been the first principal to attempt serious farming at Norway House. By 1919, under his direction, 30 of the 40 acres on which the school was situated had been cleared (ploughing under the old mission graveyard in the process) and several acres brought under cultivation: “This year we have corn for table use, a good number of tomatoes ripening on the vines and almost every variety of garden produce. We had oats ripen by Aug. 20. We are only able to raise a little compared with what we need. In three years, we have increased our cattle from five to twenty-four. Our hogs from none at that time to twenty-four, sixteen of these are large ones . . . We had one team then now two and we expect to get another.”[41]

In order to increase production further, Denys started developing land on Hope Island, some ten kilometres across the lake from the residence, as a woodlot and hayfield. His petition to have 571.2 acres there turned over permanently to the school for its use was granted in 1923 by federal order-in-council.[42] In later years, Hope Island served as pasturage as well. Principal Shoup increased the dairy herd to provide milk for the children.[43] And in 1942, Principal Caldwell introduced goats for the same purpose as well as to instruct students in their care and feed.[44]

Though it was no longer farmed, Hope Island still served in the 1960s as a site for student camping trips.[45]

Curriculum

Vocational instruction at Norway House Residential School appears to have been limited, in the case of boys, to carpentry (in effect, building the school’s outbuildings) and farming for the school’s food. These chores came to occupy so much of the children’s time, however, that in 1923 the Indian Agent complained that they were spending too much time outdoors, building fences and breaking new ground: “Pupils under the age of 16 at least, or Grade 6 or even 7, should have at least half day classroom work.”[46] Student labour, however, was crucial to the school’s operation. In 1934 Principal Shoup asked permission to keep children who had reached the age of 16 in school just to help run the place: “Up to sixteen the pupil is not able to be of any very marked assistance with the regular work of the school except for lighter tasks. During the years from sixteen to eighteen we find the pupils are able to carry our [sic] heavier tasks and so take the place of help that would have to be hired from the outside.”[47]

Both school administrators and DIA officials were aware that the skills taught at Norway House Residential School were not the ones students would most need once they left the school. In direct contrast to Rev. Shoup’s proposal to keep students longer, Indian Agent P.G. Lazenby proposed discharging boys at the age of 14 so they could return home and learn how to make a living: “Boys cannot learn to hunt and trap and fish at school, and these are the only means of earning a living in this country.”[48] Similarly, in 1935, Principal Chapin allowed eight boys to go trap muskrats with men from the community as “they would thus get good instruction in the methods of trapping, which is, after all, what they will depend upon for their living after they leave school.”[49]

In an attempt to secure boy students just such a future, in 1942 the school reached an agreement with the Hudson’s Bay Company in which the company pledged to hire Norway House Residential School graduates. Although the company preferred boys who had reached 17 or 18 years of age, they were willing to hire them at 16.[50]

The situation of girls was perceived differently. At 16, school administrators thought them too young for hospital work, domestic service, or marriage and sought to keep them a year or two longer at the school.[51]

Second Fire, 1946

On May 29, 1946, the school building was consumed by a fire that had started in the furnace room. Thanks to the efforts of two boys who woke them and helped them down the fire escape pillars, all the children and the staff escaped safely.[52]

Ruby Beardy provided the following account of the fire, as told to her by her husband, Donald Beardy, one of the heroes that night:

The fire started at 2:30 during the night. Donald was awakened by a burning sensation in his nose. When he opened his eyes, the dormitory was filled with smoke. Donald jumped out of his bed and ran towards the window which had been partially open. He pushed the screen out and looked down onto the ground. He could see flames gushing out from the wood bin in the furnace room. Instinctively, he woke up his friend, Oliver Sinclair, who was sleeping in the bed next to his. Oliver leaped up and obediently followed Donald’s orders. The two young boys quickly woke up everyone, telling each one to make much noise. All the boys began to bang and hit the beds. They did this to wake up the little girls who were sleeping in another dormitory just below their floor. Donald ran out of the dormitory to take up the boys’ supervisor, Mr. Organ, who then went and rang the fire alarm. Mr Organ told Donald to go outside and catch the girls as they came flying down the fire escape pillars. Meanwhile, Oliver was catching the boys at their fire escape. Less than a half hour later, all the children were out of the building and secure in the care of local people who had run to the burning building to help.[53]

The children stayed in local homes until they were able to return to their own communities.

In the wake of the fire, the United Church debated whether or not to rebuild. There was growing interest from First Nations communities to have federally supported local day schools on their reserves and growing pressure from within the church to get out of school administration altogether. In the end, however, church officials, pointing to the “pathetically inadequate” state of the day schools, were not convinced that the federal government was serious about giving Indigenous children an education.[54] The church rebuilt in 1952, with room for 120 students in two dorms housed in separate buildings in order to minimize the risk of fire.[55] The half-day system was abandoned.

By 1964, there were 138 children in residence at Norway House Residential School and 242 day students who lived in their own homes in the community.[56] Margaret Ann Reid recalled her experiences as a young teacher of the grade 2/3 class: “Progress was slow for many of the children—this was partly due to the language barrier —schoolwork was in English—the students were accustomed to talking and thinking in Cree. There were no restrictions on speaking Cree outside the classroom.” Reid also noted that attendance continued to be very fluid in the school, as children frequently stayed home to care for siblings or to accompany their families on trapping and fishing excursions.[57]

School Closure

In December 1965, the Hudson’s Bay Presbytery of the United Church agreed to have the Board of Home Missions negotiate with the government for the closure of Norway House Residential School at the earliest possible date. Under the United Church of Canada proposal, the residence was to be converted to classroom space for the day school, and the day school was to be administered by the federal government for Indigenous children of any Christian denomination.[58] Indian Affairs closed the residence on June 30, 1967.

Footnotes

- Margaret Anne (Reid) May, “A Northern Adventure: My Adventure at Norway House, Manitoba, August 1957–June 1959,” 2007, PP93/3289, United Church of Canada (UCC) Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Manitoba. Canada. “Norway House Cree Nation, First Nation No. 278,” 2004–2005 First Nations Profiles—MB Region. ↩

- Kenneth S. Coates, William R. Morrison, Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada “Treaty Research Report—Treaty Five (1875).” Because of the limited potential for agriculture, the reserves at Norway House and other locations were considerably smaller than the reserves established in the prairies.↩

- E.R. Young, The Apostle of the North, Rev. JamesEvans (Toronto: William Briggs, 1900), cited in Russell T. Ferrier, Superintendent of Indian Missions, to N.O. Cote, Controller, Land Patents Branch, Feb. 24, 1925, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). ↩

- J.D. McLean, Deputy SGIA, to A. Sutherland, General Secretary, Methodist Missionary Society, Apr. 19, 1898, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- E.F. Hardiman, principal, to SGIA, June 30, 1902, Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual reports, 1902, pp. 305–306. ↩

- Sutherland to Secretary General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), Dec. 6, 1900, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- J.A. Lousley, principal, to SGIA, Aug. 8, 1903, DIA annual report, 1903, pp. 336–337; “The Report of Rev. J.A. Lousley, Principal of the Norway House (Methodist) Boarding School, Norway House, Man., for the Year Ended March 31, 1913,” DIA annual reports, 1913, pp. 555–556. ↩

- J.K. McLean, surveyor, to J.D. McLean, Secretary, DIA, Aug. 13, 1910, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- Ferrier to Secretary, DIA, Mar. 20, 1913, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Norway House Agency,” DIA annual reports, 1915, pp. 163–164. ↩

- For example, Cormie wrote in 1944 regarding school-aged children at Island Lake, “A few used to go to the Norway House School but there are few, if any, going there today.” Cormie to George Dorey, Sept. 16, 1944, correspondence, Brandon Residential School, 1938–1953, 509/2/2-5, box J, file 2, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- J.G. Stewart, Indian Agent, “Monthly Report of the Norway House Boarding School, Apr. 30, 1915,” RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. According to the Methodist Church’s Superintendent of Missions, Lousley’s ultimate goal was to have the school enlarged to hold 160 children. Ferrier to Secretary, DIA, June 11, 1915, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Stewart, “Monthly Report of the Norway House Boarding School, Apr. 30, 1915”; “Extract from Report from Agent Jones on Norway House Boarding School, dated June 30, 1916”; and William Gordon, Indian Agent, to [A.F. MacKenzie], Assistant Deputy and Secretary, DIA, Oct. 7, 1925—all in RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Stewart, “Monthly Report of the Norway House Boarding School, Apr. 30, 1915”; Stewart to Duncan C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, June 15, 1915; John R. Bunn, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to Scott, Sept. 24, 1915; W.W. Shoup, principal, to MacKenzie, Jan. 5, 1932—all in RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- MacKenzie to Gordon, Sept. 23, 1925, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Lousley to Jacob Berens, Chief, Jan. 16, 1916; J.A. Lousley to T.H. Carter, Indian Agent, Aug. 11, 1915; and Carter to Scott, Mar. 11, 1916—all in RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Berens to Bunn, Jan. 12, 1916, and Lousley to Berens, Jan. 16, 1916, both in RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Berens to Lousley, Feb. 20, 1916; Carter to Scott, Mar. 11, 1916; Ferrier to Secretary, DIA, July 17, 1916—all in RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- R.T. Chapin, principal, to P.G. Lazenby, Indian Agent, June 21, 1935, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- MacKenzie to P.G. Lazenby, Indian Agent, July 17, 1935, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- May, “A Northern Adventure.” ↩

- “Extract from Annual Report, E.J. Hardiman to SGIA,” RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Lousley to Frank Pedley, Deputy SGIA, Apr. 9, 1910, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- John Semmens, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to David Laird, Indian Commissioner, Sept. 7, 1907, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1. See also C.C. Caverley, Indian Agent, to Laird, Apr. 9, 1907; Chief [Sinclair] to Laird, Feb. 14, [1907]; [J.A.J. McKenna], Assistant Indian Commissioner to Semmens, July 3, 1907; Ferrier to McKenna, report, [c. July 30, 1907]; and Martin Benson, Schools Division, to Deputy SGIA, Sept. 28, 1907—all in RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Semmens to Laird, Sept. 7, 1907. ↩

- Ferrier to Secretary, DIA, July 24, 1915, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581–1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Stewart, “Monthly Report of the Norway House Boarding School, Apr. 30, 1915.” ↩

- Shroup to McKenzie, Jan. 13, 1934, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- A.H. Allard, C.C. RCMP, Manitoba District to Commissioner, RCMP, Ottawa, Report on Conclusion of Case, RG10, vol. 6288, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- R.L. Steveston to R.B. Cochrane, Feb. 27, 1934, acc. 1983.050c, box 18, file 185, United Church of Canada Archives (UCCA). ↩

- Ibid.; V.N. Trupel, Medical Superintendent, Norway House Hospital, to [Secretary and Executive of the Mission Board], Feb. 9, 1934, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Melissa Stoops, “Health Conditions at Norway House Residential School, 1900–1946,” M.A. thesis, McMaster University, Jan. 1, 2006, p. 91. ↩

- E.L. Stone, Health and Disease at the Norway House Indian Agency, 1925, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Provincial Archives of Manitoba, A.95/53, p. 256, cited in Stoops, 16. ↩

- Lousely to SGIA, Aug. 8, 1903, DIA annual reports, 1903, pp. 336–337. ↩

- Shoup to MacKenzie, Jan. 5, 1932. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- R.T. Chapin, “Memoirs of a Happy Journey Through Life,” 1972, Ex-89, no. 3070, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives, as cited in Stoops, 96. ↩

- Stewart to Sir, June 19, 1915, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- John R. Bunn, Inspector of Indian Agencies, to Duncan C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, Sept. 24, 1915, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- George F. Denyes to Secretary, DIA, Aug. 28, 1919, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. Regarding destruction of the graveyard and community responses, see Ferrier, “Report of the Work at Norway House,” RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Canada, P.C. 863, May 18, 1923, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- R.L. Steveston to Rev. R.B. Cochrane, Feb. 27, 1934, access. 1983.050c, box 18, file 185, UCCA. ↩

- Cochrane to R.A. Hoey, Superintendent of Welfare and Training, Indian Affairs, Dec. 3, 1941, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

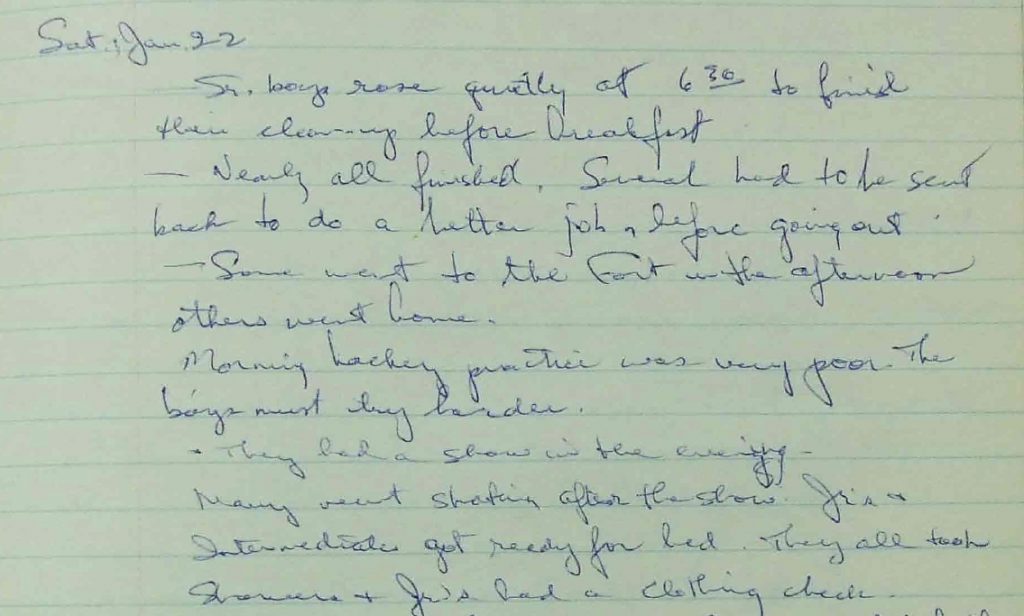

- Brian Ronden, supervisor and housemaster, Norway House IRS, diary, 1963–1964, 509/3, file 20, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- “Extract from letter of Wm. Gordon, Indian Agent, Norway House, Dated July 2, 1923,” RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Shroup to DIA, June 230, 1934, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- Lazenby to Secretary, DIA, July 17, 1937, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- Lazenby to Secretary, DIA, April 25, 1935, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- J.W. Henley, Personnel Manager, Hudson’s Bay Company, to Caldwell, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Chapin to Philip Phelan, Chief Training Division, DIA, July 6, 1940, RG10, vol. 6269, file 581-10, LAC. ↩

- Hoey to Acting Deputy Minister, May 29, 1946, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Byron Apetagon, Norway House Anthology: Stories of the Elders (Winnipeg: Frontier School Division No. 48, 1991), vol. 1, p. 51. ↩

- J. Freeman, Chair, Special Committee, Hudson Bay Presbytery, “Report Re: Future Policy of the United Church in Relation to Day Schools, Residential Schools and Their Administration in Indian Communities,” November 1965, 503-9, file 1, UCC Prairie to Pine Regional Council Archives. ↩

- Hoey to Director, Lands and Services, Nov. 20, 1947, RG10, vol. 6268, file 581-1, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Freeman, “Report Re: Future Policy.” ↩

- May, “A Northern Adventure.” ↩

- E.E.M. Joblin to R.F. Davey, Education Services, Indian Affairs Branch, Dec. 20, 1965, file 123/25-1-5, DIAND Residential Schools Records Office. ↩