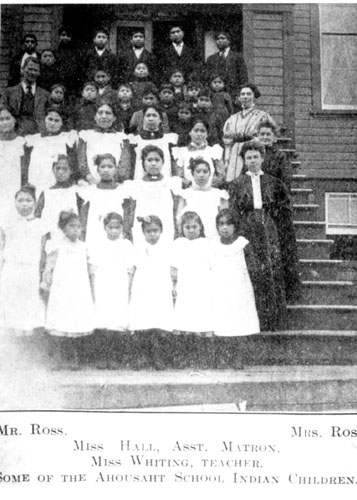

Ahousaht Residential School

Ahousaht Residential School Timeline

Dates of Operation

1895–1904 (day school / informal boarding school), 1904–1916, 1918–1940

Operated by The Presbyterian Church in Canada, and, after 1925, by the Board of Home Missions of The United Church of Canada. The school building was owned by the Women’s Missionary Society of The Presbyterian Church in Canada, which also nominated staff and contributed financially to the school for most of its history.

Location

Just south of the Marktosis 15, of the Ahousaht First Nation, on the southeast end of Flores Island, Clayoquot Sound, off the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The school was on land the Women’s Missionary Society purchased outside of the reserve, two kilometres from the Ahousaht village, and about 20 kilometres north of Tofino

A number of the Indians were frightened and compelled to sign a paper and give up these children to this new [Presbyterian] teachers, and for them to have control of the children until they are 16 years of age. We know how 2 of the same kind of teacher assaulted an old white man here and took his children by force from him and why because their mother Ahouset Indian was a Catholic and so was the children. We don’t want such trouble here, we did not ask for these new people to come here, the church-house belonging to our old teacher the [Roman Catholic] Priest was standing here on our land, and they could see it alright, so why did they come here to make trouble.

—petition from Chief Billy, old Chief Moquiney, Chief Benson, Chief Atlin, and Chief Nokamas.[1]

In June 1904, just months before the new Ahousaht Residential School was set to start its first school year under the direction of the Presbyterian Church, five Ahousaht chiefs sent the government a petition. In it, they protested Presbyterian incursions in their community and accused missionary John Russell of keeping children at the school against their parents’ wishes. The petition is one of several written by community members over the years contesting actions by the Church and the residential school. Community members often invoked the bitter rivalry between the Presbyterian and Roman Catholic churches—both present in Ahousaht and both competing for adherents—in their efforts to steer the school in directions more in line with Ahousaht values and practice. It was a bargaining chip few Indigenous communities had, but lost much of its power as the Presbyterians became more entrenched in the village.

Establishment

In November 1895, Reverend Melvin Swartout, the Presbyterian missionary at Ucluelet, on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, applied to the local Indian Agent for funding to open a day school on the Ahousaht reserve.[2] According to Swartout, the Roman Catholic Church had had a school at Ahousaht for a few seasons, but it had been abandoned.[3]

Indeed, that school had moved, to Clayoquot (Tofino), just 20 kilometres away, because the Department of Indian Affairs would not finance it. But the Catholics still had a church and mission in the village and in many of the surrounding villages, too. The Department of Indian Affairs decided it was better to let things be.

Undeterred, the next month the Church’s Committee on Foreign Missions opened a small day school in Ahousaht under Reverend John W. Russell. Within a few years, the Women’s Missionary Society had financed construction of a day school and a mission house on the Marktosis Reserve and were paying Russell’s salary as well as those of two teachers and an assistant.[4] In 1899, the Indian Department reconsidered and agreed to issue an annual grant of $300 as Russell’s salary.[5]

It wasn’t long before the Presbyterian Church approached the Indian Department again—this time for a residential school. The Department of Indian Affairs, however, questioned the need for a residential school when attendance at the day school was excellent and the children already learned from their parents all the vocational skills—sealing, fishing, and “native” industries—that they would need as adults.[6] Once again, the Department was also concerned about creating friction with the Roman Catholic Church. “The Presbyterians have a boarding school at Alberni and the Roman Catholics have a similar one at Clayoquot,” wrote Martin Benson, of the Department of Indian Affairs’ schools branch. “This about evens matters in this locality.”[7]

But the Presbyterians pushed ahead. Russell invited parents, who left the reserve during long stretches of the year, to leave their children with him so they could attend school. By 1903, he had 26 children boarding with him and his family. Perhaps not surprisingly, Mrs. Russell’s health suffered, and her husband had to resign his post.[8]

Russell’s resignation appears to have forced the issue, and within the year, the Women’s Missionary Society had offered to pay for a residential school building if the Department of Indian Affairs would provide a per capita grant. The Department agreed, and in 1904, Ahousaht Residential School opened under Reverend J.C. Butchart. The three-storey school building, with accommodation for 50 children, took one or two years more to complete.

In the fall of 1916, the school burned down. Principal Hugh W. Vanderveen continued offering classes at Ahousaht on a day school basis, obtaining the sanction and support of the Department of Indian Affairs to do so. But after a year or so, the day school was considered a failure, and the Women’s Missionary Society decided to rebuild.[9] The Society provided a new residence, smaller than the last, with room for 25 students. Most students came from the Ahousaht village, and occasionally children from the neighbouring Nuu-chah-nulth communities of Ehattesaht, Kelsemeht, and Ucluelet appeared on the roll.

Relationship with Ahousaht Community

The relationship between Ahousaht Residential School and the neighbouring Ahousaht village, the source of most of the school’s students, was rocky at times, especially during the school’s early years. In addition to initial protests against the residential school, in 1907, the death of student Will Maquinna, son of hereditary chief Billy, precipitated a major crisis. Community leaders petitioned to have the staff replaced, and parents pulled their children from the residence.[10] In the wake of the boy’s death, chief Billy, a man of “considerable influence with the Band,” had, in the Indian Agent’s words, “left no stone unturned to injure the school.”[11]

It appears that Billy was angry with the school not just because his son had died on their watch, but because of the way Will’s death had been handled. During an interview with the school inspector, Billy explained: “Will died in the School, and when I see the teachers at the School I shall feel ashamed, but if new teachers come I can shake hands with them and not feel ashamed.” To right the situation according to Nuu-chah-nulth protocol, Billy asked Principal J.L. Millar to give him 50 blankets to potlatch, but Millar refused. Instead he paid for the two blankets used to bury the boy.[12]

The issue of potlatching arose again in relation to the school. The potlatch, a Chinook term referring to a range of important political and economic ceremonies of northern coastal Aboriginal communities, had been outlawed under the Indian Act in 1885. In 1914, Billy August accused Principal John Ross of conspiring to have four Ahousaht people, including August’s wife, jailed and fined for potlatching. “He is not good teaching for the Childrens he is Policeman,” August wrote.[13] The Department of Indian Affairs exonerated Ross of any blame in the convictions, but acknowledged that the complaints came because of Ross’s active assistance to the Indian Agent in attempting to stop the potlatch.

Curriculum

In addition to the academic subjects authorized by the Indian Department, Ahousaht, like other residential schools, provided vocational training. For most of the school’s history, however, this training was carried out on an informal basis without dedicated instructors. And unlike many schools, Ahousaht did not, except in its final years, follow the half-day system, (classes in the morning and vocation training in the afternoon). The children attended two hours of classes in the morning and two in the afternoon, and they went home for a few hours on Saturdays. When the school first opened, the boys’ “industries” consisted primarily of cutting wood. The girls assisted in the laundry, baked bread, sewed, and performed other housekeeping duties.[14]

By 1910, the boys were taking on major construction projects: they built the barn, the workshop, the girls’ pavilion, plank sidewalks between the buildings, and over the summer holidays they painted the entire school. In fact, virtually all construction at the school over the years was carried out with the boys’ labour. They also helped in the laundry and bake-house and learned shoe-making.[15]

In the 1930s, the school incorporated boat-building into the boys’ training, and erected a new shop, with a launching slip, for the purpose. The students built at least two 40-foot motorized launches: one in 1934 and one in 1939. Ahousaht parents were anxious to see more marine-related training at the school and approached school inspector Gerald H. Barry to have “some sort of training for their boys in the maintenance and repair of marine engines” added to the curriculum.[16] Barry supported the request, recommending also that the school switch to the half-day system and hire a manual training instructor. The next year, his recommendations were implemented, but the new instructor left a year later and the school was never able to retain another.

In general, however, work performed by both boys and girls at the school, was, in Barry’s view, “not anything more than just the ordinary everyday work of the school” and of little use to the pupils on graduation. The girls, for instance, “simply learn by doing the various operations” of cooking, housework, mending and sewing. Regarding the boys’ training, he wrote, “Too much time has been given to clearing land which I much doubt will ever be used.”[17]

Discipline

Discipline and the general tenor of the school appears to have depended to some extent on the practices of its various administrators. One letter described Ross as “always angry.”[18] Under Joseph Jones, according to Inspector Barry, there was “little if any corporal punishment.”[19] In a composition entitled “Our School,” student Joseph Titian described some of the institution’s rules: “The teachers don’t allow us to go home with out permission for if we do they will punish us. We are not also to speak in our Indian language for if we do we are to stay in School on Saturdays…They are very strict to us in the School especially when we are studying our lessons. They tell us from time to time not to be idle.”[20] Elder Elsie Robinson, who attended the school from the ages of seven to 17, more recently described the physical abuse she experienced: “We had to always do whatever they said, and they were always holding a big stick, ready to hit you if you didn’t obey.”[21]

General Conditions and Student Health

According to the principals’ annual reports, from the school’s official opening in 1904 to 1916 (the last year the Department of Indian Affairs annual reports provide detailed information on the schools), deaths among students at Ahousaht Residential School averaged one to two a year, from an average school population of 35. Children in poor health were generally discharged, accounting for student deaths outside the school as well. In 1911, for instance, Principal Ross reported that from a list of 16 ex-students, six had died, all from tuberculosis.[22]

Principal William R. Wood saw a connection between ill health and the conditions at the school. In 1929, he reported that there was an unusual number of deaths and discharges due to poor health, and that the school had few healthy children in attendance. He wrote, “When one recognizes that they sleep in dormitories from which the chill of the B.C. [British Columbia] winter is never removed by artificial heat, that the water they drink is never ordinarily drinkable, and that the toilet system exhibits none of the features of ordinary decency, much less comfort, one cannot but have misgivings as to the cause of some of their troubles.”[23] Wood, himself, retired before his first year of administering the school was up—because of poor health.[24]

Nonetheless, his plea for better conditions found a hearing, as the next several years saw piecemeal improvements to the school: heating and plumbing in 1929; a new well in 1930; an electrical plant and lighting in 1931; a new septic tank in 1933, and in 1936, a residence for the principal and his family. Despite these renovations, the main school building was becoming less and less habitable, and fire was a constant hazard. In 1937, Isabel Loveys of the Woman’s Missionary Society recommended that no further expenditures be made on the building, as the Department of Indian Affairs had condemned it.[25]

Staff

Conditions at Ahousaht Residential School were difficult for the children, but also for the staff and administrators, who found both the work and the isolation very hard. In her letters home, day school teacher Elizabeth Vicar wrote of the never-ending rain, but also the tremendous beauty of the place: “This is the darndest place—one minute you utterly loath it and the next you are breathless in admiration.”[26] With some important exceptions staff turnover was high.[27] So was the toll on staff health. Of Ahousaht’s eight administrators, two resigned because of their wives’ poor health; one, because of his own health; and one had a stroke on the job. A.E. Caldwell, whose wife had to retire because of illness, remained until the school burned down in 1940, but only with the aid of barbiturates.[28]

School Closing

Towards six in the evening on January 26, 1940, a fire broke out in the upstairs dorm of Ahousaht Residential School and within the hour the entire building was consumed. The fire, the second to destroy the school, was a disaster waiting to happen. Every inspector’s report for six years previous had noted the threat of fire. In response, escapes had been built and fire drills held. In 1936, a night watchman was hired. But these measures could not change the fact that Ahousaht was “a fire trap and a menace,” without enough water to put out a blaze once it started.[29] In 1938, the Indian Agent wrote, “I am…convinced that, should fire occur in the night, very few would escape.”[30] Luckily, the 1940 fire, reportedly caused by faulty wiring, started while the children were in the dining room. No injuries were reported or lives lost.

Students who were not from Ahousaht were accompanied home and later entered day schools at Alberni and Ucluelet. The Ahousaht children continued classes on a day school basis in the classroom building, which had not been harmed, until a permanent day school could be erected in the village.[31] Almost half the Ahousaht children were later transferred to Alberni Residential School.[32] Ahousaht Residential School remained closed.

Footnotes

- Chief Billy et al to Clifford Sifton, Secretary General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), June 30, 1904, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt. 1, Library and Archives Canada. The foregoing is an extract of the original letter, which does not appear in the file. However, a Departmental response is on file, which refers to “the detention at school (against the wishes of their father) of two children from your reserve” and states that “the Department has secured their discharge and taken steps to prevent a repetition of this occurence.” See S. Stewart, Assistant Secretary, Department of Indian Affairs, to Chief Billy, Oct. 14, 1904, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- M. Swartout to H. Guillod, Indian Agent, Nov. 1, 1895, RG10, vol. 6422, file 868-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Swartout to A.W. Vowell, Superintendent, April 30, 1898, RG10, vol. 6422, file 868-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- J. Campbell, Conv. F.M. Com., to Vowell, July 18, 1901, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt.1, LAC; J.C. Butchart, principal, to SGIA, July 2, 1904, Department of Indian Affairs annual report, 1904, p. 390. ↩

- 5. Benson to Secretary, DIA, June 9, 1899, RG10, vol. 6422, file 868-I, pt. 1, LAC; R.P. MacKay, secretary, General Assembly Committee on Foreign Missions, to Sifton, Nov. 7, 1901, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt.1, LAC; DIA annual report, 1900, p. J-152. ↩

- Benson to Secretary, DIA, Nov. 7, 1901, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt.1, LAC. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- [MacKay?] to Frank Pedley, Deputy SGIA, Aug. 10, 1903, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt.1, LAC. ↩

- J.H. Edmison, Board of Home Missions, to J.D. McLean, Deputy SGIA, May 29, 1918, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Chief Bill et al to Secretary, DIA, Jan. 26, 1907, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- A.W. Neill, Indian Agent, to unknown, [c. March 1907], RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- [R.?]E. Green, Inspector, to Vowell, Apr. 16, 1907, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Billy August to Secretary, DIA, Nov. 25, 1914, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Butchart to SGIA, July 2, 1904. ↩

- “The Report of Mr. John T. Ross, principal of the boarding school, Ahousaht, B.C., for the year ended March 31, 1910,” DIA annual report, 1910, pp. 521–522. ↩

- Gerald H. Barry, “Inspector’s Report on Ahousaht Indian Residential School,” Mar. 24, 1936, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Barry, “Inspector’s Report on Ahousaht Indian Residential School,” Apr. 5, 1937, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Ahousaht Young Peoples Society, per Billy August, to the Secretary, DIA, Dec. 24, 1914, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Barry, “Inspector’s Report on Ahousaht Indian Residential School,” April 24, 1934. ↩

- Joseph Titian, “Our School,” [c. May 1910], RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Elsie Robinson, interviewed by Richard Wright, in “We have to Turn the Page on the Past,” The United Church Observer, January 2010. ↩

- “The Report of Mr. John T. Ross, principal of the boarding school, Ahousaht, B.C., for the year ended March 31, 1911,” DIA annual report, 1911, pp. 592–593. ↩

- William R. Wood, principal, to Neill, Feb. 5, 1929, and Wood to Duncan C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, Feb. 4, 1929, both in RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-5, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Wood to Secretary, DIA, Nov. 1, 1929, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-5, pt. 2, LAC. ↩

- Isabel McIntosh Loveys, “Ahousaht,” Oct. 1937, accession 1983.058C, box 114, file 13, United Church of Canada Archives (UCCA); Barry to D.M. MacKay, Indian Commissioner for B.C., Apr. 15, 1937, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-6, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Beth to Everyone, Nov. 2, 1947, accession 1983.050C, box 14, file 13, UCCA. ↩

- Andrew S. Grant, General Superintendent of Home Missions, to Secretary, DIA, Oct. 20, 1914, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Barry, “Inspector’s Report on Ahousaht Indian Residential School,” Apr. 4, 1939. ↩

- Barry, “Inspector’s Report on Ahousaht Indian Residential School,” Apr. 5, 1937. ↩

- Ashbridge, “Report for month of November 1939,” Nov. 30, 1938, RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-5, pt. 4, LAC. ↩

- P.B. Ashbridge, Indian Agent, “Agent’s Report on Fire Ahousaht Indian Residential School” [c. Jan. 31, 1940], RG10, vol. 6430, file 876-5, pt. 4, LAC. See also Ashbridge to Mackay, Indian Commissioner for B.C., Feb. 9, 1940, RG10, vol. 6422, file 868-5, pt. 1, LAC. At the time of the fire, 30 of the 70 children in residence came from “various points on the Coast,” and the remainder, from Ahousaht village. ↩

- Ashbridge to MacKay, Feb. 9, 1940. ↩