Kitimaat Residential School (Elizabeth Long Memorial Home)

Kitimaat Residential School (Elizabeth Long Memorial Home) Timeline

Dates of Operation

1894–1898 (informal boarding school), 1899–1908 (Girls’ Home), 1908–1941 (Elizabeth Long Memorial Home)

Operated by the Women’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church and, after 1925, by the Women’s Missionary Society of the United Church.

Location

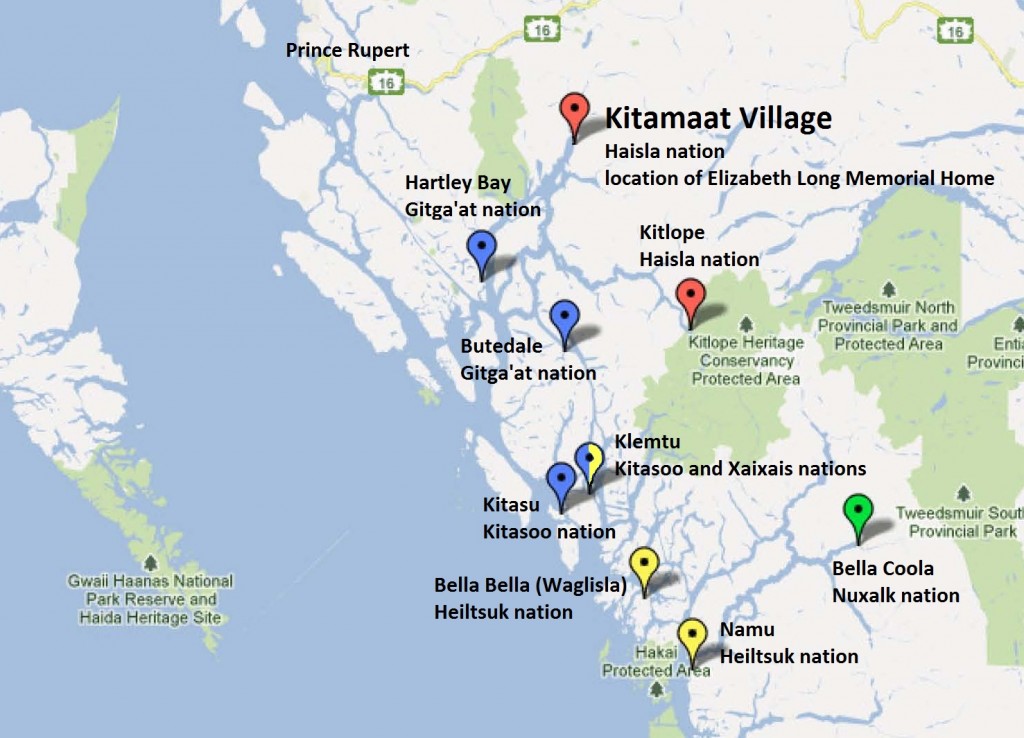

Kitamaat Village, a reserve of the Haisla Nation, located near the head of Douglas Channel in northern British Columbia, some 120 kilometres southeast of Prince Rupert.

Next come the Parents: parents sick, who want their children to scrub; Parents departing from the village, who want their children for the day; Parents returning to the Village, who also want their children for the day; Parents irate because their children have colds & are not properly looked after. Grandparents dying who want their grandchildren to see them die & so on & so forth. That part does not bother me much. I have Authority to say “No” & do not mind saying it if I think necessary.[1]

Margaret Butcher, teacher

In 1917, Margaret Butcher, a nurse who worked at the Elizabeth Long Memorial Home for Girls first as a sewing teacher and later as matron, described the daily interactions she had with the parents of children who resided in the home. Unlike many residential schools, the Elizabeth Long Memorial Home was located in the Haisla village from which most of its boarders came. In fact, it stood right above Kitamaat’s main street. Children from the home also attended day school with other children from the locality. This situation made for close and sometimes complicated relations with the people of the village. Butcher’s efforts to control access to parents was not always successful: children moved back and forth between the home and the village, and missionary women “also crossed the threshhold into Haisla homes.”[2] Such proximity appears to have allowed Haisla children at the home greater access to their families, language, and culture than was the case in many of the other, larger residential schools and the industrial institutes.

Establishment of the Girls’ Home

Waks Gamalayu (Charlie Amos), a Haisla man who converted to Methodism during a visit to Victoria in 1876, first brought Christianity to Kitamaat. A small number of Haisla soon joined him, incorporating Methodism into their religious practices as part of a larger Indigenous strategy to counter colonialism’s assault on Haisla lands and culture. In the early 1880s, Methodist converts urged teachers at Port Simpson to relocate to Kitamaat, which a number of them did, including Tsimshian leaders George Edgar and Chief Alfred Dudoward, and Susanna Lawrence, the first white missionary at Kitamaat, who ran the village day school.[3]

In 1893, the Methodist Church appointed Rev. George Raley and his wife, Maude, to the mission at Kitamaat. Within a year the Raleys had set up temporary quarters for children whose parents spent part of the year away from the village fishing and working in the canneries so that they could stay behind and attend school. Girls were housed in a building made of rough boards that contained a dorm, a small kitchen, a washroom and a storeroom. The schoolboys slept behind a partition in the day school. Twenty-two Haisla children, ages eight to 16, were boarded in this manner. “They brought their own bedding and dishes, and such a motley array I had never seen, nor had I seen such queerly clad boys and girls,” wrote Maude Raley.[4]

The Raleys soon found funding from the Board of Home Missions and the Women’s Missionary Society for a more permanent arrangement. A new mission house was built in 1895, which would also serve as a “home,” with 20 children sleeping in the mission house itself and 10 in an outbuilding. Miss Elizabeth Long, the home’s first matron, wrote of her first winter there, “The Home was a very rough building, with only one board between us and the cold…I always wore a coat, cap and rubbers. The girls wore coats, handkerchiefs and, when very cold, shawls. Even then, though we had large fires, we could not keep warm.”[5]

In 1899, the WMS took the home over, had a new two-storey building constructed, and provided for an assistant matron. The new home would board girls, exclusively. There were 29 in residence the first year. The Kitamaat Band set aside land for the building site, on a hill above the village’s main street, and helped erect the building. They also made an annual contribution of food and wood. “When they have money they give liberally,” the WMS noted.[6]

According to its administrators, the food supplied at the home was “Native” as far as possible “so that [the girls] may not be unfitted for their future life.” The WMS reported that one season, the girls “dried and smoked 30,000 small fish for their own use. These all had to be washed through three waters, salted, then strung on sticks and placed in the smoke-house.”[7] Long also described the preference for Indigenous foods at the home: “In cooking the oolachan grease is always used. This is a trial to the teachers…but we find the children need it.”[8]

The Methodists were driven by an impulse to “save” Indigenous girls from what they deemed to be a demoralizing traditional life. As George Raley recalled in the community paper Na-na-kwa, “The needs of the children immediately aroused my sympathies. Their condition was deplorable. I found them requiring help of a very practical character, in order that they might be saved physically and morally.”[9] In an attempt to keep the girls from marrying before they reached what the Methodists considered an appropriate age, “a wedding outfit was offered those who would remain [at] Home until eighteen years of age.”[10]

The Girls’ Home burned down on May 20, 1906.

Elizabeth Long Memorial Home

In 1908, the WMS financed construction of a new home to replace the one that burned. Named the Elizabeth Long Memorial Home (after Long, who had died in 1907), it was two storeys tall, plus attic and basement. In addition to girls, the new home would receive eight to ten boys under the age of 12. Twenty-seven children were admitted the first year.[11] A water system brought water in pipes from a small mountain reservoir to taps on each floor, both hot and cold. During the summer months, however, the reservoir often ran dry, and sometimes the pipes froze in winter for up to five months. On these occasions the only recourse was to carry water from a well.[12] Sewage was carried by pipe to the seashore, and a hot air furnace provided heat.[13]

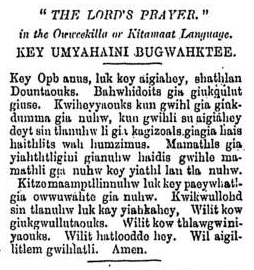

The children attended classes at the day school in the morning and afternoon, together with day students from the village. Back at the home, they spent another hour in the evening reviewing, and by 1912 the older girls were studying music.[14] The girls took turns helping with the cooking, and were also taught gardening, bread-making, general housework, sewing, laundry, and fancy work. The boys’ chores included cutting up and carrying wood, cleaning, garden work, and general work around the home.[15] It proved difficult to prevent the children from speaking Haisla: “It is an endless struggle to get the children to talk English among themselves,” the WMS reported, leading the residence’s staff to introduce a “reward system” to encourage the use of English only.[16] The children spent Saturdays afternoons with their families in the village “provided they were ‘called for’ and brought back.”[17]

In 1911, the home managed for the first time to secure funding from the federal government. The Board of Home Missions and the Indian Department signed an agreement whereby the DIA provided a residential school per capita grant of $100 to a maximum of 20 students, and the church paid for maintenance and equipment.[18] Two years later the grant was raised to $125 to a maximum of 30 students.[19]

Children enrolled in the residence initially came exclusively from Kitamaat Village and neighbouring Kitlope, and they spoke Haisla at home. However, in 1916, the missionary at Bella Coola sent six Nuxalk girls, accompanied by the Indian Agent, to take up residence at the home. Staff worker Margaret Butcher described their arrival: “Poor little souls, it was an immense ordeal for them. Leaving their parents & all home surroundings to take a 3 days journey with white men to a strange place like this Home! They understood neither English nor Kitamaat so it was fortunate they were six and could speak to each other but they were almost too scared to do so.”[20]

The following years saw the enrolment of Gitga’at children from Hartley Bay and Butedale, who were Tsimshian speaking. By the 1930s, the student population also included children from Bella Bella (Waglisla) and Namu, who were Hailhzaqvla-speaking members of the Heiltsuk nation, and from Kitasu, of the Tsimshian-speaking Kitasoo Nation. Children from Klemtu were of both the Hailhzaqvla-speaking Xai’xais Nation and the Kitasoo Nation.

Throughout the home’s history, girl residents outnumbered boys by at least two to one. Whereas girls remained at the school “until married or discharged,” boys were discharged when they reached 12 years of age and were usually transferred to Coqualeetza Residential School, in Sardis, some 700 kilometres away.[21] In 1934, the DIA agreed to lower the age of transfer to Coqualeetza to 10 years old, in part to ease overcrowding in the Kitamaat day school classroom but also “to place the boys under the influence of a staff where men are in the majority rather than leaving them to a staff which is composed entirely of women.”[22]

In line with Department of Indian Affairs regulations, children at the Elizabeth Long Memorial Home were initially given one months’ holiday in summertime. During this time, many children accompanied their families to work at the canneries. Matron E.J. Donogh complained in 1911 that “when the day for opening came, only two little tots returned. The others came when they got ready—as I understand they have been in the habit of doing.”[23]

The problem of truancy at the start of the school year finally led the principal to ask, in 1928, to have its summer vacations extended to two months in order to better accommodate family schedules: “It is impossible for these children to get out and return in 43 days. The people are always anxious to get away by the fifteenth of June…To get back in forty three days would mean they would have to return by the end of July, and their people are not then through the fishing.”[24] The Department of Indian Affairs granted the request.[25]

Conditions and Community Relations

There was a great deal of illness at Kitamaat during the early years of the residential school. Shortly after the Girls’ Home opened in 1899, “serious epidemics of measles, German measles and la grippe followed each other in quick succession,”[26] and in 1902 a flu epidemic of eight weeks’ duration saw almost every girl in the home taken ill.[27] Again, from 1918 to 1919 during the Spanish influenza pandemic, every child in the home came down with the disease and at least one died.[28] A whooping cough epidemic hit just months after the Spanish flu subsided and took the life of another child. Although the village had a resident nurse to help in such emergencies, the nearest doctor was 120 kilometres away in Prince Rupert, and boats came to the village only once a month.

Beyond recurring epidemics of contagious illnesses, tuberculosis was the predominant threat. Margaret Butcher recorded in her journal that one family lost five of its six daughters who had been in the home to the disease.[29] Butcher also wrote that during her first seven months at the home, eight of her former pupils had died.[30] The situation led her to exclaim in one letter, “Which one will die next?” and to ask Miss Clarke, then matron of the home, whether “civilization” could be the cause.[31]

In 1922, when yet another schoolgirl at the home fell ill and died, Kitamaat parents took action. They pulled their children from the residence and refused to return them. In consultations with one another, the parents discovered that “of all the girls who have attended the school 49 have died, and 50 are alive.”[32] A petition from the Haisla people of the village, signed “by practically every one of them old enough to sign,” called for the dismissal of the entire home staff, who, they said, had not provided their children with good or sufficient food and clothing and had not given them proper medical care.

These grievances prompted an investigation by the RCMP, who attended a meeting of community members, home officials, the missionaries, and the Indian Agent. After listening to a mix of threats and promises from the RCMP constable and the Indian Agent, parents agreed to return their children if Principal Clarke “would sign her name to a paper before us that she would see that the children got all the food they wanted, that they would be well cared for, and be supplied with sufficient clothing.” Clarke signed.[33]

The home was already unpopular with many Kitamaat people before the 1922 boycott, and continued to be long afterward. In 1926, for example, the DIA reminded Thomas Ferrier, of the Board of Home Missions, to ensure the children at Kitamaat were well fed because “the rather unfortunate attitude of the Indian parents on the reserve makes it imperative that this school be conducted in an exemplary manner.”[34] WMS records and Butcher’s letters attest to many instances of intervention by Kitamaat parents and community members.

Relations with Day School and Closure of the Residence

Another ongoing conflict at Kitamaat stemmed from the situation at the day school, which served both children living in the village and those residing at the Elizabeth Long Memorial Home. Parents of day school children charged that “the teacher gave most of her attention to the boarding school children.”[35] Overcrowding was also a problem. “I do not consider that the children from the residential school should be permitted to crowd the village children out of the day school,” Inspector G.H. Barry wrote in 1933, after eight village boys were denied admittance because, with 59 children on the roll, there was no more room.[36]

Barry thought that the home, as the beneficiary of a residential school per capita grant, should provide its children with schooling as well as room and board. He also rejected proposals to relieve the day school by sending more children away, citing the day school’s “rightful purpose of accommodating the village children, who should not be sent to Coqualeetza except in exceptional circumstances.”[37] Noting potential savings as well, Barry and other DIA officials began to push for the home’s closure in favour of a new and larger day school.[38]

In 1940, that day school was built, and the next year the DIA unilaterally closed the home. The United Church Board of Home Missions accepted but was not pleased with the government’s decision. In a petition, Kitamaat chief Richard Morrison, representing the Kitamaat Band, and mission workers opposed the home’s closure, arguing that the home was essential to the village’s economy, since it allowed the children to receive “uninterrupted education” while their parents travelled to work in the fishing, logging, and trapping industries.[39] Elizabeth Loveys, of the WMS, wrote that without the home, “because of the transent life of these people it would have been almost impossible for any continuity of education.”[40] The Indian Department stood its ground, however, arguing that the Indians had been “pampered” long enough.[41]

Footnotes

- Mary-Ellen Kelm, ed., The Letters of Margaret Butcher: Missionary-Imperialism on the North Pacific Coast (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2006), 69. ↩

- Ibid., 243. ↩

- Thomas Crosby, Up and Down the Coast by Canoe and Mission Ship (Toronto: Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, 1914), 250–263. ↩

- H.L. Platt, “Girls’ Home, Kitamaat, B.C.,” ch. 6 in The Story of the Years: a History of the Woman’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, Canada, from 1881 to 1906 (n.p.: [Women’s Missionary Society Methodist Church Canada], 1908), vol. 1, p. 69. ↩

- Ibid., 71. ↩

- Ibid., 72. ↩

- Ibid., 73. ↩

- Elizabeth Emsley Long, How the Light Came to Kitamaat (n.p.: united Church of Canada, 1907). ↩

- George H. Raley, “The Kitamaat Home,” Na-na-kwa or Dawn on the Northwest Coast, 9 (January 1900): 1. ↩

- Platt, “Girls’ Home, Kitamaat, B.C.,” 74. ↩

- E.S. Strachan and W.E. Ross, “Girls’ Home, Kitamaat, B.C.: Elizabeth Long Memorial Home,” ch. 2 of The Story of the Years: a History of the Woman’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church, Canada, from 1906 to 1916 (Toronto: Women’s Missionary Society Methodist Church Canada, 1917), vol. 3, p. 26. ↩

- Ibid.; “Extract from Inspector Greens [sic] Report on the Kitamaat Boarding School (Methodist) in the Bella Coola Agency Inspected July 11th and 12th, 1912,” and “Extract from Report of G.H. Barry, Inspector of Indian School, Dated April 30 and May 1, 1931, on his Inspection of the Kitamaat Indian Residential School,” both in RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-5, pt. 1, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). ↩

- E. Lorenz, Indian Agent, to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs (SGIA), June 5, 1909, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- A.E. Green, Inspector, to Frank Pedley, Indian Agent, Apr. 2, 1909, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC; “The Report of Miss E.J. Donogh, Matron of the Kitamaat Boarding School, Kitamaat, B.C., for the year ended March 31, 1912,” Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) annual report, 1912, p. 587. ↩

- Green to Pedley, Apr. 2, 1909; Lorenz to SGIA, June 5, 1909. ↩

- Strachan and Ross, “Girls’ Home, Kitamaat, B.C.: Elizabeth Long Memorial Home,” 28. ↩

- Kelm, The Letters of Margaret Butcher, 67. ↩

- T. Ferrier, Superintendent of Methodist Indian Schools and Hospitals, to Duncan C. Scott, Deputy SGIA, June 9, 1911, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC; J.D. McLean, Deputy and Secretary, DIA, to Iver Fougner, Indian Agent, Nov. 30, 1911, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-5, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- McLean to Fougner, May 6, 1913, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Kelm, ed., The Letters of Margaret Butcher, 29. ↩

- S.E. Alton, Secretary of Home, to Secretary, DIA, Aug. 6, 1912, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Kenneth J. Beaton, Board of Home Missions, to Secretary, DIA, Mar. 6, 1934, and A.F. MacKenzie, Secretary, DIA, to Beaton, Mar. 15, 1934, both in RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- E.J. Donogh, principal, to the Secretary, DIA, Dec. [?] 1911, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Sanna Runacres, principal, to Fougner, June 30, 1928, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- W.E. Ditchburn, Indian Commissioner for B.C., to Fougner, Aug. 11, 1928, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Platt, “Girls’ Home, Kitamaat, B.C.,” 72 ↩

- bid., 74. ↩

- Kelm, ed. The Letters of Margaret Butcher, 182–184. ↩

- Kelm, Colonizing Bodies: Aboriginal Health and Healing in British Columbia, 1900–50 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1998), 64. ↩

- Kelm, ed. The Letters of Margaret Butcher, 60. ↩

- Ibid., 85. ↩

- Fougner to Secretary, DIA, June 15, 1922, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- R.W. Clearwater, RCMP, “Re: Kitamaat School,” report, June 13, 1922, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- McLean to Ferrier, May 17, 1926, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Extract from the Report on Inspector Cairns of the Kitimaat [sic] Day Sch.,” Apr. 16, 1917, RG10, vol. 6396, file 820-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- “Extract from Report of Mr. G.H. Barry, Inspector of Schools, on His Visit to the Kitamaat Residential School on May 6th, Last,” [1933], RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-5, pt. 1, LAC; “Extract from Report of Mr. G.H. Barry, Inspector of Schools, Dated April 30 and May 1, 1931…” ↩

- “Extract from Report of Mr. G.H. Barry…on May 6th, Last,” [1933]. ↩

- [MacKay, Indian Commissioner], “Kitamaat Indian Residential and Day Schools,” Sept. 28, 1938, RG10, vol. 6451, file 883-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩

- Richard Morrison et al, “RE: the Elizabeth Long Memorial home, Kitamaat Indian Reserve, B.C.,” Feb. 1, 1941, accession 1983.058C, box 14, file 16, United Church of Canada Archives (UCCA). ↩

- Isabel Loveys, “My visit to Kitamaat,” September 1937, accession 1983.058C, box 14, file 16, UCCA. ↩

- Christie to Sir, May 21, 1941, RG10, vol. 6396, file 820-1, pt. 1, LAC. ↩